An infectious diseases detection platform developed by University of Pittsburgh scientists working with UPMC infection preventionists proved over a two-year trial that it stops outbreaks, saves lives and cuts costs.

The results are published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, making the case for adoption in hospitals nationwide and the development of a national early outbreak detection database.

READ MORE: Surveillance system detected infection linked to eye drops months before outbreak declared

READ MORE: Deadly bacteria developed the ability to produce antimicrobials and wiped-out competitors

“We saved lives while saving money. This isn’t theoretical – this happened in a real hospital with real patients,” said lead author Alexander Sundermann, Dr.P.H., assistant professor of infectious diseases in Pitt’s School of Medicine. “And it could easily be scaled. The more hospitals implement this practice, the more everyone benefits, not just by stopping previously undetected outbreaks within the walls of the hospital, but by finding medical device or medication-linked outbreaks sweeping the nation.”

Genomic sequencing

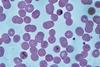

The Enhanced Detection System for Healthcare-Associated Transmission (EDS-HAT) takes advantage of increasingly affordable genomic sequencing to analyze infectious disease samples from patients. When the sequencing detects that any two or more patients have near-identical strains of an infection, it flags the results for the hospital’s infection prevention team to find the commonality and stop the transmission.

Without genomic sequencing, hospital infection preventionists have no way of knowing if two hospitalized patients coincidentally have the same infection or if one of them was infected by the other. Because of this, patients with the same type of infection who don’t have an obvious link – such as staying in the same inpatient unit – may unknowingly spread the infection, leading to an outbreak growing significantly before it is detected. Conversely, infection preventionists may spend time and resources trying to avert a nonexistent outbreak when patients happen to have the same type of infection, but the transmission was from unrelated sources.

Prevention and savings

The study ran from November 2021 through October 2023 at UPMC Presbyterian Hospital. During that time, the analysis showed that EDS-HAT prevented 62 infections and five deaths, compared to if the system had not been running. It netted a savings of nearly $700,000 in infection treatment costs – a 3.2-fold return on investment.

“These results are remarkable,” said co-author Graham Snyder, M.D., M.S., medical director of infection prevention and hospital epidemiology at UPMC. “This project clearly illustrates how UPMC’s academic partnership with Pitt is providing our patients with outstanding patient care while creating innovative solutions that pave the way for better patient care worldwide.”

If health care facilities across the U.S. adopt EDS-HAT, a nationwide outbreak system could be developed, similar to PulseNet, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s network for detecting multistate outbreaks of foodborne illness. Sundermann and colleagues previously found that, had such a system existed, the 2023 outbreak of deadly bacteria linked to contaminated eye drops could have been stopped far earlier.

No-brainer

“It is a no-brainer to implement EDS-HAT at every health care facility nationwide,” said senior author Lee Harrison, M.D., professor of infectious diseases at Pitt’s School of Medicine and of epidemiology at Pitt’s School of Public Health. “We hope these findings will contribute to ongoing conversations among U.S. health care leadership, payors and policymakers about the benefits of genomic surveillance as standard practice in health care.”

Additional authors of this research are Praveen Kumar, Ph.D., Marissa P. Griffith, Kady D. Waggle, M.S., Vatsala Rangachar Srinivasa, M.P.H., Nathan Raabe, M.P.H., Emma G. Mills, Hunter Coyle, Deena Ereifej, M.P.H., Hanna M. Creager, Ph.D., Ashley Ayres, M.B.A., Daria Van Tyne, Ph.D., Lora Lee Pless, Ph.D., and Mark Roberts, M.D., all of Pitt, UPMC or both.

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant R01AI127472.

No comments yet