A vaccine candidate against Lassa virus completely protected guinea pigs exposed to an otherwise lethal dose of the virus, researchers from Texas Biomedical Research Institute (Texas Biomed), The Scripps Research Institute and The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) recently reported in npj Vaccines.

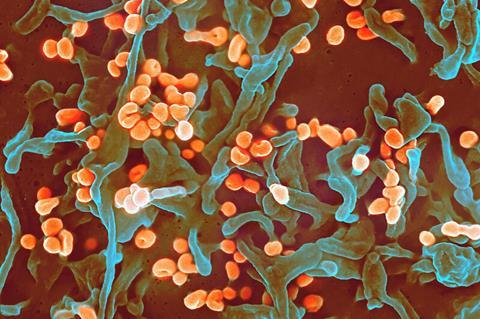

Lassa virus, which has no approved vaccine and no cure, causes tens to hundreds of thousands of cases of Lassa fever annually. It is passed from infected rodents to people through contaminated food or surfaces. While many people have no symptoms, the virus can cause fever, severe bleeding and organ failure within two weeks of infection. Fatality rates are estimated to be around 15–20%. Found throughout Western Africa, Lassa fever is a priority disease for vaccine research and development according to The World Health Organization because it presents a high potential for a public health emergency.

Vaccine candidate

Texas Biomed Professor Luis Martínez-Sobrido, PhD, and Scripps Research Institute Professor Juan Carlos de la Torre, PhD, have been working on a Lassa virus vaccine candidate for the past 10 years.

They have focused on developing a live-attenuated vaccine, which includes a live but weakened or “attenuated” version of the virus. Other live-attenuated vaccines already in use include those for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR), smallpox, chickenpox and yellow fever.

“A live-attenuated vaccine can offer longer-lasting and broader protection because now your body’s immune system is being trained to recognize the entire virus—not just one small piece of it,” Dr. Martínez-Sobrido said.

Live-attenuated vaccine

A key requirement for any live-attenuated vaccine is to ensure it has been modified in such a way it cannot revert to its original form nor mix together with other natural circulating strains and cause disease. While unlikely, this latter scenario could potentially happen if a person was vaccinated and infected around the same time.

READ MORE: Researchers develop promising Lassa fever vaccine

READ MORE: Researchers uncover genetic factors for severe Lassa fever

Dr. Martínez-Sobrido and Dr. de la Torre combined their distinct approaches to attenuate Lassa virus by tweaking both sections of its genome, which consists of a small segment and large segment.

Specifically, Dr. Martínez-Sobrido and his team used a technique called codon deoptimization to edit the RNA in the small segment to turn down production of a key protein responsible for binding the virus to infected cells. Meanwhile, Dr. de la Torre and his team replaced part of the large segment RNA with the corresponding part from the small segment. Together, these edits produce a modified virus that still looks enough like the real thing to prompt the desired immune response but cannot cause illness or disease.

Two approaches combined

“By combining our two attenuation approaches, it makes for unbreakable attenuation,” said Dr. Martínez-Sobrido. “We’ve attenuated both segments of the virus and so if either segment were to recombine with a wild virus, the resulting virus will still be attenuated and unable to cause disease.”

In the paper, the researchers demonstrated the attenuated virus’s robust safety profile, reduced replication (also known as loss of fitness) and that it did not evolve to regain virulence (the ability to cause disease). Moreover, the study, which was completed in collaboration with NIAID’s Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick, showed very promising efficacy results. The study involved 50 guinea pigs, divided into groups that received the vaccine and those that remained unvaccinated. Following an exposure to a normally lethal dose of the virus, the vaccinated guinea pigs remained healthy and showed no adverse side effects.

“It was 100% protective, which is exactly what you want,” Dr. Martínez-Sobrido said.

The team next plans to study the vaccine in nonhuman primates, the current gold standard to evaluate if vaccines are safe and effective before moving forward to clinical trials in people.

No comments yet