Scientists from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, together with colleagues from the University of Montpellier in France and the University of Oldenburg in Germany, have tested how a fever could affect the development of antimicrobial resistance.

In laboratory experiments, they found that a small increase in temperature from 37 to 40 degrees Celsius drastically changed the mutation frequency in E. coli bacteria, which facilitates the development of resistance. If these results can be replicated in human patients, fever control could be a new way to mitigate the emergence of antibiotic resistance. The results were published in the journal JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance of pathogens is a worldwide problem, and recognized by the WHO as one of the top global public health and development threats. There are two ways to fight this: by developing new drugs, or by preventing the development of resistance.

“We know that temperature affects the mutation rate in bacteria,” explains Timo van Eldijk, co-first author of the paper. “What we wanted to find out was how the increase in temperature associated with fever influences the mutation rate towards antibiotic resistance.”

Three antibiotics

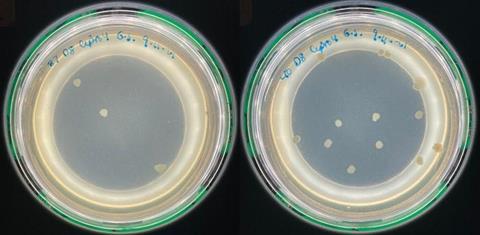

”Most studies on resistance mutations were done by lowering the ambient temperature, and none, as far as we know, used a moderate increase above normal body temperature,” Van Eldijk reports. Together with Master’s student Eleanor Sheridan, Van Eldijk cultured E. coli bacteria at 37 or 40 degrees Celsius, and subsequently exposed them to three different antibiotics to assess the effect.

”Again, some previous human trials have looked at temperature and antibiotics, but in these studies the type of drug was not controlled.” In their laboratory study, the team used three different antibiotics with different modes of action: ciprofloxacin, rifampicin, and ampicillin.

The results showed that for two of the drugs, ciprofloxacin and rifampicin, increased temperature led to an increase in the mutation rate towards resistance. However, the third drug, ampicillin, caused a decrease in the mutation rate towards resistance at fever temperatures. ”To be certain of this result, we actually replicated the study with ampicillin in two different labs, at the University of Groningen and the University of Montpellier, and got the same result,” says Van Eldijk.

Fever-suppressing drugs

The researchers hypothesized that a temperature dependence of the efficacy of ampicillin could explain this result, and confirmed this in an experiment. This explains why ampicillin resistance is less likely to arise at 40 degrees Celsius.

”Our study shows that a very mild change in temperature can drastically change the mutation rate towards resistance to antimicrobials,” concludes Van Eldijk. “This is interesting, as other parameters such as the growth rate do not seem to change.”

If the results are replicated in humans, this could open the way to tackling antimicrobial resistance by lowering the temperature with fever-suppressing drugs, or by giving patients with a fever antimicrobial drugs with higher efficacy at higher temperatures. The team concludes in the paper: “An optimized combination of antibiotics and fever suppression strategies may be a new weapon in the battle against antibiotic resistance.”

No comments yet