Scientists at ADA Forsyth Institute (AFI) have identified a critical factor that may contribute to the spread of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), shedding light on why these infections are so difficult to combat. Their study reveals that the dangerous multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogen, Klebsiella, thrives under nutrient-deprived polymicrobial community conditions found in hospital environments.

According to the World Health Organization, HAIs pose significant risks to patients, often resulting in prolonged hospital stays, severe health complications, and a 10% mortality rate. One of the well-known challenging aspects of treating HAIs is the pathogens’ resistance to multiple drugs. In a recent study published in Microbiome, AFI scientists discovered that Klebsiella colonizing a healthy person not only have natural MDR capability, but also dominate the bacterial community when starved of nutrients.

Outcompeting others

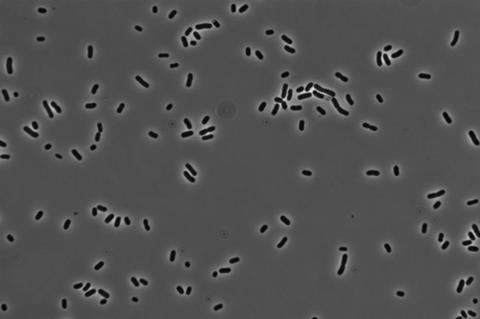

“Our research demonstrated that Klebsiella can outcompete other microorganisms in its community when deprived of nutrients,” said Batbileg Bor, PhD, associate professor at AFI and principal investigator of the study. “We analyzed samples of saliva and nasal fluids to observe Klebsiella’s response to starvation conditions. Remarkably, in such conditions, Klebsiella rapidly proliferates, dominating the entire microbial community as all other bacteria die off.”

READ MORE: Carbon limitation boosts survival of beneficial bacterium in the human gut

READ MORE: Two ways that members of the microbiome fight salmonella infections

Klebsiella is one of the top three pathogens responsible for HAIs, including pneumonia and irritable bowel disease. As colonizing opportunistic pathogens, they naturally inhabit the oral and nasal cavities of healthy individuals but can become pathogenic under certain conditions. “Hospital environments provide ideal conditions for Klebsiella to spread,” explained Dr. Bor. “Nasal or saliva droplets on hospital surfaces, sink drains, and the mouths and throats of patients on ventilators, are all starvation environments.”

Oral reservoir

Dr. Bor further elaborated, “When a patient is placed on a ventilator, they stop receiving food by mouth, causing the bacteria in their mouth to be deprived of nutrients and Klebsiella possibly outcompete other oral bacteria. The oral and nasal cavities may serve as reservoirs for multiple opportunistic pathogens this way.”

Additionally, Klebsiella can derive nutrients from dead bacteria, allowing it to survive for extended periods under starvation conditions. The researchers found that whenever Klebsiella was present in the oral or nasal samples, they persisted for over 120 days after being deprived of nutrition.

Saliva bacteria

Other notable findings from the study include the observation that Klebsiella from the oral cavity, which harbors a diverse microbial community, was less prevalent and abundant than those from the nasal cavity, a less diverse environment. These findings suggest that microbial diversity and specific commensal (non-pathogenic) saliva bacteria may play a crucial role in limiting the overgrowth of Klebsiella species.

The groundbreaking research conducted by AFI scientists offers new insights into the transmission and spread of hospital-acquired infections, paving the way for more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Additional collaborators on the project include: Xuesong He, Alex S. Grossman, Jett Liu, Nell Spencer, Wenyuan Shi, and Hatice Hasturk of ADA Forsyth; Daniel R. Utter of California Institute of Technology; Lei Lei of Sichuan University; Nidia Castro dos Santos of Guarulhos University; and Jonathon L. Baker of Oregon Health & Science University.

No comments yet