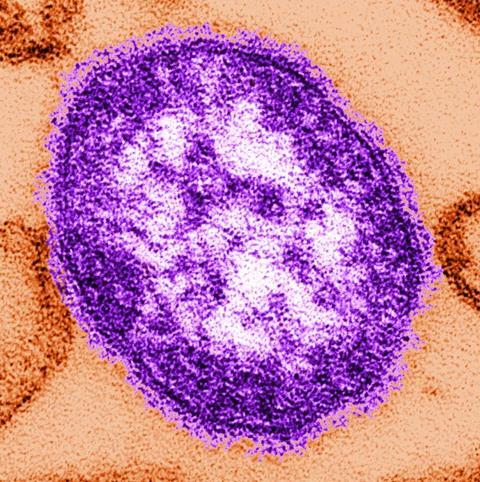

Mayo Clinic researchers mapped how the measles virus mutated and spread in the brain of a person who succumbed to a rare, lethal brain disease. New cases of this disease, which is a complication of the measles virus, may occur as measles reemerges among the unvaccinated, say researchers.

Using the latest tools in genetic sequencing, researchers at Mayo Clinic reconstructed how a collective of viral genomes colonized a human brain. The virus acquired distinct mutations that drove the spread of the virus from the frontal cortex outward.

“Our study provides compelling data that shows how viral RNA mutated and spread throughout a human organ — the brain, in this case,” says Roberto Cattaneo, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic virologist who is a co-lead author on a new PLOS Pathogens study. “Our discoveries will help studying and understanding how other viruses persist and adapt to the human brain, causing disease. This knowledge may facilitate the generation of effective antiviral drugs.”

Contagious disease

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases. The measles virus infects the upper respiratory tract where it uses the trachea, or windpipe, as a trampoline to launch and spread through droplets dispersed when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

Dr. Cattaneo pioneered studies on how the measles virus spreads throughout the body.

He first began to study the measles virus about 40 years ago and was fascinated by the rare, lethal brain disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), which occurs in about 1 in every 10,000 measles cases. It can take about five to 10 years after the initial infection for the measles virus to mutate and spread throughout the brain. Symptoms of this progressive neurological disease include memory loss, seizures and immobility. Dr. Cattaneo studied SSPE for several years until the lethal disease nearly disappeared as more people were vaccinated against measles.

Measles resurging

However, measles is resurging due to vaccine hesitancy and missed vaccinations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of children missed receiving their measles vaccinations, which has resulted in an estimated 18% increase in measles cases and 43% increase in death from measles in 2021 compared to 2022 worldwide, according to a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report.

“We suspect SSPE cases will rise again as well. This is sad because this horrible disease can be prevented by vaccination. But now we are in the position to study SSPE with modern, genetic sequencing technology and learn more about it,” says Iris Yousaf, co-lead author of the study and a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate at Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

Dr. Cattaneo and Yousaf had a unique research opportunity through a collaboration with the CDC. They studied the brain of a person who had contracted measles as a child and had succumbed to SSPE years later as an adult. They investigated 15 specimens from different regions of the brain and conducted genetic sequencing on each region to piece together the puzzle of how the measles virus mutated and spread.

Changing genome

The researchers discovered that, after the measles virus entered the brain, its genome — the complete set of genetic material for the virus — began to change in harmful ways. The genome replicated, creating other genomes that were slightly different. Then, these genomes replicated again — resulting in more genomes that were each a little different as well. The virus did this multiple times, creating a population of varied genomes.

“In this population, two specific genomes had a combination of characteristics that worked together to promote virus spread from the initial location of the infection — the frontal cortex of the brain — out to colonize the entire organ,” says Dr. Cattaneo.

The next steps in this research are to understand how specific mutations favor virus spread in the brain. These studies will be done in cultivated brain cells and in clusters of cells resembling the brain called organoids. This knowledge may help in creating effective antiviral drugs to combat virus spread in the brain. However, pharmacological intervention in advanced disease stages is challenging. Preventing SSPE through measles vaccination remains the best method.

No comments yet