Umeå University researchers, Sweden, have unveiled how the most common white blood cells, neutrophils, counter Candida albicans toxin, stopping its tracks.

“We found that when exposed to the toxin of the fungal pathogen, neutrophils trigger processes to release a chromatin meshwork which entangles and restrains Candida albicans hyphae,” said Constantin Urban, Professor of Immunology at the Department of Clinical Microbiology at Umeå university, Sweden, and supervising investigator of the study.

Systemic infections caused by bacterial and fungal organisms frequently result in a clinical condition termed sepsis which is a leading cause of death of critically ill patients and is considered a global threat. According to the World Health Organization, sepsis is estimated to affect more than 30 million people worldwide every year, leading to an estimated number of six million fatal cases. C. albicans is the most frequent human fungal pathogen and a common cause of invasive candidiasis which may result in sepsis.

Reversible switch

A hallmark of C. albicans virulence is the ability to reversibly switch from yeast forms to filamentous forms, hyphae. The organism uses the yeast form to rapidly increase biomass and the hyphae to invade and damage tissue.

While a large proportion of the world population is colonized by C. albicans since birth, those with a weakened immune system due to disease or medical intervention are at risk to develop severe or even life-threatening infections, including sepsis, caused by this fungal organism. Neutrophils, the most abundant white blood cell, are an essential part in the defence against fungal microbes.

The newly published study sheds light on how neutrophils respond to C. albicans hyphae, which release a peptide toxin called candidalysin. Notably, candidalysin is exclusively secreted when C. albicans grows as hyphae and hence during invasive growth.

Triggering pathways

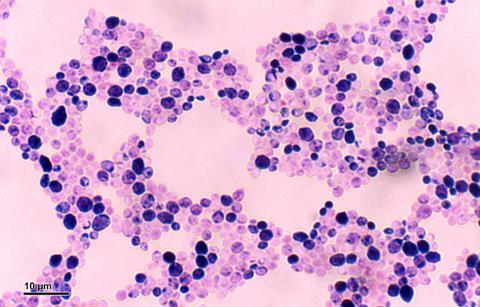

The researchers observed that neutrophils triggered cellular pathways which cumulated in the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These chromatin fibres are formidable weapons against hyphae.

NETs can entrap and inhibit the fungus with the help of large amounts of sticky and antimicrobial proteins located within the structures. The sticky nature of NET proteins efficiently binds microbes, such as fungal cells. The entangled fungus subsequently is attacked by the associated antimicrobial NET proteins.

“We were very surprised to see that neutrophils remained functional in the presence of candidalysin for such a long time. The immune cells continued to produce antimicrobial oxidants and continued to engulf fungal cells,” says Constantin Urban.

Engineered strains

In contrast, when neutrophils were infected with engineered strains of C. albicans lacking candidalysin, NET formation was virtually absent.

“Interestingly, candidalysin alone was not a sufficient stimulus to induce NET formation. It resulted in a more compact, less fibrous chromatin meshwork released by neutrophils, so-called NET-like structures, whereas only the combination of candidalysin exposure to and pattern recognition of C. albicans cells by neutrophils resulted in release of fibrous NETs,” said Lucas Unger, research assistant at the Department of Clinical Microbiology at Umeå University at the time of the study, lead experimental researcher of the study.

The study unravels that candidalysin mainly contributes to chromatin swelling – an early step in the release of extracellular DNA structures – via calcium-dependent activation.

Recognition of fungal cells

Through effects upon neutrophil membranes, calcium ions are allowed to enter the cells to start these activation processes. The recognition of fungal cells via neutrophil receptor molecules triggers kinase activation and production of antimicrobial oxidants. Calcium influx, kinase activation and oxidant production in combination eventually induce the release of large amounts of NETs.

This work was only possible with engaged international collaborators located in Gothenburg in Sweden, Bristol and London in the United Kingdom, and Jena and Berlin in Germany.

“We are particularly grateful to clinicians from the Charité hospital in Berlin that allowed us access to neutrophils from patients with chronic granulomatous disease. The immunodeficiency renders neutrophils unable to produce antimicrobial oxidants and with the help of these we could thoroughly address the involvement of oxidants in candidalysin-triggered processes,” says Constantin Urban.

The results have been published in EMBO Reports.

No comments yet