Farmers growing lettuce prefer varieties that are resistant to various diseases, including downy mildew, a common plant disease that causes yellow or brown spots on the upper surfaces of leaves. Delft scientists investigated downy mildew infections in lettuce, a plant species where such infections are typically only visible in their later stages.

READ MORE: Rapid platform uses plant sentinel response to detect foodborne pathogens

READ MORE: Paper-based biosensor offers fast, easy detction of fecal contamination on produce farms

“There are indeed lettuce varieties that are resistant to downy mildew, but similar to the coronavirus, the disease continually evolves into new variants that can still infect resistant plants. This forces scientists and breeders into a constant race to develop new resistant crops in response to evolving diseases,” explains physicist Jos de Wit, who collaborated with biologists from Utrecht University for his doctoral research.

Real-time tracking

To cultivate crops like lettuce that can better withstand diseases, researchers from Delft University of Technology and Utrecht University have developed a method that allows for imaging common plant infections. For the first time, this can be done without killing the plant and significantly faster than conventional microscopy.

“Until now, researchers had to kill a plant for each step in the process, stain it, and then examine it under a microscope,” says Jeroen Kalkman, associate professor in imaging physics. “Now, with this new imaging technique, we can track how a disease develops in a living plant in real-time.”

Higher yields

Plant scientists often don’t know how an infection progresses within a plant and what makes certain crops insensitive to pathogens. This new instrument provides insights, aiding in the cultivation of crops with broader resistance to various diseases.

“These crops require fewer pesticides, are better equipped to withstand extreme weather conditions, and ultimately yield much more. This means that, in the long run, more people on Earth can be fed,” Kalkman notes.

Mapping plant diseases

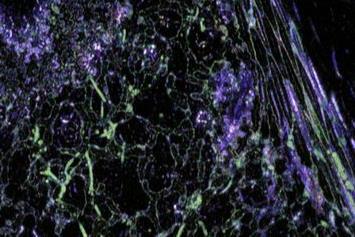

“The technique we used is called dynamic optical coherence tomography (dOCT),” says De Wit. “It involves emitting light and measuring the time it takes for that light to reflect back, similar to ultrasound but with light instead of sound. In just one and a half seconds, we can capture around 50 to 100 images of an infected lettuce leaf. We can effectively map plant diseases with dOCT because the pathogens move more than the plant cells. By assigning colours to areas with more movement, we can generate a strong contrast between the pathogen and the plant. Without dOCT, the disease would only be visible at a much later stage.”

A practical tool

In addition to lettuce, the researchers have demonstrated that their instrument also works for other crops, such as radishes and peppers carrying parasitic roundworms. Further research is needed however to make this technique a user-friendly tool for biologists without a technical background. Kalkman says: “I am eager to continue this research to bridge the gap between technology and biology.”

No comments yet