As new stretches of coastline become vulnerable to potential Vibrio outbreaks in a warming aquatic environment, AMI member Elizabeth Archer examines how human health is inextricably linked with ocean health.

Coastal environments are some of the most complex and diverse on our planet. They are also disproportionately affected by urbanization, pollution and climate change impacts with consequences for ocean and human health. In a Personal View for the Lancet Planetary Health, colleagues and I discuss the increasing prevalence and geographical spread of human infections caused by marine Vibrio bacteria in response to environmental and demographic change. Below is an overview of the key messages.

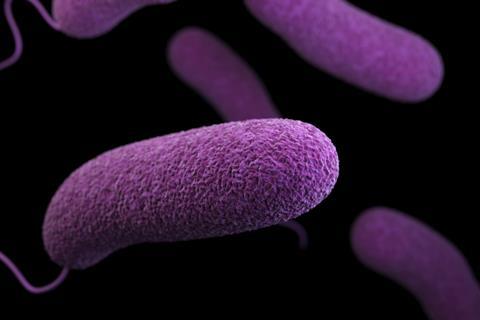

Vibrio bacteria are pervasive in the marine environment; most are harmless to humans and fulfil different functional roles in the ocean. Yet, at least 12 species are known to cause illness in humans with the most infamous, O1/O139 Vibrio cholerae, causing the diarrheal disease cholera. Whilst cholera remains a critical health challenge, particularly in developing countries, bathing-associated wound infections and seafood-borne illnesses caused by other Vibrio pathogens are an emerging threat to human health in need of greater public awareness.

Temperature sensitivity

Over recent decades non-cholera Vibrio infections, also referred to as ‘vibriosis’, have emerged at greater distances from the subtropical regions where they were first reported. Key to the geographic expansion of vibriosis infections is the temperature sensitivity of these bacteria.

READ MORE: Vibrio natriegens offers low cost and low capital plasmid engineering

READ MORE: Sticky Vibrio teams with seaweed and plastic to stir up perfect storm

Vibrio pathogens thrive in warm (~20°C), low salinity waters typical of estuaries and coastal flood waters. They have evolved to replicate rapidly under suitable environmental conditions and so are highly responsive to upshifts in water temperature.

For example, summer heatwaves have facilitated surges in bathing-related vibriosis cases in Northern Europe’s Baltic Sea, with several cases reported less than 100 miles from the Arctic Circle in 2014.

Vibriosis septicaemia

Vibriosis infections vary in severity according to the causative Vibrio species and health of the infected person. Cases of mild gastroenteritis from seafood consumption may resolve without treatment in a healthy individual and most wound infections are healed with antibiotics.

However, Vibrio vulnificus is of particular concern to ageing populations with rising rates of chronic conditions that increase a person’s susceptibility to infection, such as liver disease. Although rare in comparison with other causes of vibriosis (V. vulnificus is attributable to around 200 of the 80,000 vibriosis cases estimated by the CDC in the United States each year), V. vulnificus infections are severe and can rapidly develop into life-threatening septicaemia.

Patients with a foodborne V. vulnificus infection have approximately a 50% survival rate whilst those who acquire a V. vulnificus wound infection often undergo limb amputation to prevent the further spread of necrotizing tissue and the bacteria entering the bloodstream.

Climate change

As average global temperatures rise with greenhouse gas emissions, heatwave events are likely to increase in frequency and intensity. Meanwhile, data from NOAA document unprecedented average global ocean temperatures for 2023 and 2024 so far. Such changes may promote the growth of Vibrio pathogens as well as encourage human recreational exposure.

One global mapping study predicts that up to 38,000km of additional coastline could host favorable conditions for Vibrio pathogens by 2100 with climate change, whilst my own work focused on V. vulnificus cases on the East Coast of the United States predicts that annual case numbers in this region may double by mid-century.

This highlights the need for greater awareness of Vibrio infections to enable prompt diagnoses and effective treatment when necessary. Above all, Vibrio pathogens serve as a reminder of the inextricable link between human health and the health of the ocean.

Dr Elizabeth Archer is a Senior Research Officer at the University of Essex. She sits on AMI’s Ocean Sustainability Scientific Advisory Group.

No comments yet