All living organisms host microbiomes composed of both beneficial and harmful microbes that influence health. Microbiome diversity affects host fitness: low diversity can lead to immune issues and poor nutrient absorption, while high diversity can boost resilience to stress and pathogens.

To illuminate this issue, researchers from Florida Atlantic University’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, have spent the last five years studying the relationships between songbird gut microbiomes and traits that relate to a bird’s health and breeding success. While links between the gut microbiome and other traits have been described in laboratory experiments with captive animals, little is known about these relationships in wild animals, and even less in birds.

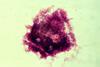

Using a common backyard bird, the Northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), a new study provides the first-ever description of how a wild bird’s microbiome relates to its ornamentation and body condition. This strikingly beautiful songbird is known for its vivid red plumage and distinctive features, which include a red beak and a black mask around the eyes.

Results of the study, published in the journal Oikos, reveal that a cardinal’s gut microbiome diversity can be predicted by its body condition, and the quality of its ornamentation – red plumage and beak.

Health tied to microbiome

“Our findings confirm the hypothesis that a wild bird’s health is tied to its microbiome, and that the ‘sexiness’ of a male’s ornaments can signal his health,” said Rindy Anderson, Ph.D., senior author and an associate professor in FAU’s Department of Biological Sciences.

This species, with its sexually selected carotenoid pigments, provided a unique opportunity to explore how these traits relate to gut microbiota. Cardinals’ vibrant coloration is a well-known example of how carotenoid pigments reflect an individual’s quality.

“This study has important applications for conservation biology and contributes to a better understanding of ways to improve animal health in settings such as wildlife hospitals, zoos and aquaria, and captive breeding programs for endangered species,” said Morgan Slevin, first author and a Ph.D. candidate in FAU’s Department of Biological Sciences.

Sexual ornaments

To test for relationships between the microbiota and host fitness, researchers sampled the cloacal microbiomes of wild cardinals and measured body condition index, assessed coloration of sexual ornaments (beak and plumage), and collected blood to estimate the glucocorticoid response to stress. To better understand the microbiota-gut-brain axis in free-living songbirds, they described the baseline relationships, or lack thereof, among multiple aspects of this system in wild cardinals.

READ MORE: Wild birds’ health and likely survival is affected by the gut microbiome

READ MORE: Symbiosis between bacteria and toxic bird yields discovery of new antimicrobials

“Overall, cardinal ornament redness and saturation positively correlate with individual quality,” said Slevin. “Thus, deeper red coloration indicates greater carotenoid pigmentation. We were able to show that a cardinal’s coloration related to its microbiome diversity.”

Both alpha and beta bacterial diversity were related to individual variation in body condition and several sexual ornaments, but not glucocorticoid concentrations. Irrespective of directionality, beak saturation also related to beta diversity, indicating that birds with more similar beak coloration profiles had more similar microbiome community structures.

Avian host fitness

“While we anticipated that birds with the most saturated beaks would be the highest quality individuals, and that the highest quality individuals would have the most diverse microbiomes, our results suggest that maintaining a diverse microbiome might instead come at a cost to beak saturation,” said Slevin.

Findings from a free-living songbird population add to a growing body of research linking avian host fitness to internal bacterial community characteristics.

“Ultimately, our study and those that follow should move us closer to answering the overall question of whether a bird’s gut microbiome can predict individual quality,” said Anderson.

No comments yet