Purdue University has received $2.7 million in federal funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to develop a field test that can measure and predict the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in a wide range of wildlife and farm animals.

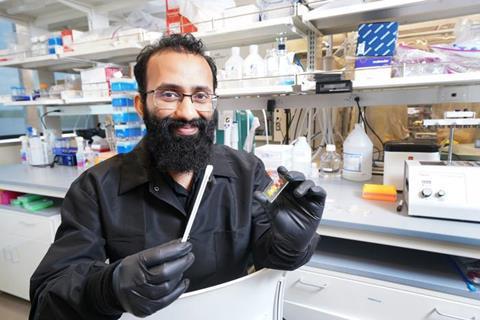

“We’re hoping to develop one protocol and that the test works universally,” said Mohit Verma, assistant professor in agricultural and biological engineering and the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering.

Verma and his colleagues plan to collect nearly 2,000 nasal and oral samples from more than three dozen species of mammals and birds ranging from cattle, swine and wolves to chickens, ducks and turkeys.

Project team

The project team includes Purdue’s Arezoo Ardekani, professor of mechanical engineering; Gregory Fraley, the Terry and Sandra Tucker Endowed Chair of Poultry Science; Jonathan (Alex) Pasternak, assistant professor of animal sciences; Jon Schoonmaker, associate professor of animal sciences; and Patrick Zollner, professor of quantitative ecology in forestry and natural resources.

They will work with additional collaborators at Purdue and other universities and at APHIS, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Great Lakes Indian Wildlife Commission and Wolf Park near Battle Ground, Indiana. Additional partners are the Native American Fish and Wildlife Society, Indiana State Poultry Association and Midwest Poultry Consortium.

Tracking transmission

The team’s goal is to provide a simple and affordable way for animal and public health agencies in tribal, state, federal and private lands to track transmission of the virus as it potentially spreads between different animal species and humans. The testing would be suitable for settings ranging from hunting, trapping and animal production to veterinary clinics and at home.

The project spans both hardware and software components. The hardware is the test for field use. The software is for uploading the results to a dashboard to monitor spread of the virus in different animals and locations.

APHIS and its partners completed studies that showed the virus spread to various animal species, wildlife included. For white-tailed deer, their research conducted in 2021 revealed that approximately 40% of the samples contained SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, suggesting that the virus was circulating in the states that were evaluated.

“There is a potential for COVID-19 to be resident in animals and then spill back to humans,” Verma said. “That’s the concern, and that can happen. That’s why we are developing better tools for surveillance in wildlife, companion animals and farm animals.”

Tribal nations

The problem disproportionally affects tribal nations, whose members maintain close contact with wildlife both for subsistence and cultural reasons. An April 2022 Congressional hearing on ’Preventing Pandemics through U.S. Wildlife-borne Disease Surveillance’ highlighted the need to involve tribal nations in the process. Likewise, the Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Geological Survey could use better surveillance tools to help guide outdoors enthusiasts nationally.

“We thought about what could be the most universal and could still be used in the field across different users,” Verma said. The team settled on oral-nasal swabs because they can sample what often is a shared cavity in animals.

The team will focus on the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but the tools could apply to other viruses and emerging diseases as needed. The project will build off Verma’s ongoing work in animal and human health. Verma hasalready developed innovative paper-based, rapid-result tests for bovine respiratory disease and COVID-19 and is in the process of commercializing these through his startup Krishi Inc.

Fast results

“We’re hoping that the tools we develop will be amendable to low-resource use and can be deployed widely,” Verma said. The availability of results could be reduced from one day to an hour at a cost of about $10 per test.

A key goal will be to improve the test’s sensitivity. Because it was designed to be simple and user-friendly, the test Verma developed for humans was less sensitive than laboratory-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) tests. Both animal size and the rate of virus replication determine the needed sensitivity level, he noted. Many animals not yet susceptible may become susceptible if the virus mutates.

“A lot of this is not known. We are comparing ourselves to what we can do in the lab,” he said. “If you take the same sample, do all the purification and extraction in the lab, then do this qPCR test, what levels can you get?”

Ideally, the team will develop a test sensitive to the virus at low levels, even before an animal begins showing clinical signs.

No comments yet