BK polyomavirus, or BKPyV, is a major cause of kidney transplant failure. There are no effective drugs to treat BKPyV. Research at the University of Alabama at Birmingham reveals new aspects of BKPyV replication, offering possible drug targets to protect transplanted kidneys.

To better understand BKPyV replication and ways to prevent it, researchers in the UAB Department of Microbiology have published a single-cell analysis of BKPyV infection in primary kidney cells. Their findings contradict a long-held understanding of the molecular events required for BKPyV production, and they offer new, potentially effective drug targets to protect transplanted kidneys, says Sunnie Thompson, Ph.D., associate professor. The study is published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

With only seven genes, the BK polyomavirus must use the host cell’s DNA replication machinery to produce new viruses. Although the virus was discovered over 50 years ago, little is known about how BKPyV gets access to cell’s replication machinery.

Apparent paradox

“This work came out of an apparent paradox,” said lead author Jason M. Needham, Ph.D. “BKPyV is able to trigger a radically different cell cycle, despite also activating cellular pathways that should block the cell cycle.”

READ MORE: Clinical trial finds live vaccinations safe for liver and kidney transplant recipients

READ MORE: Hepatitis E virus attacks nerve cells

The prevailing model suggests that BKPyV expresses a protein called large tumor antigen, or TAg, early during infection. Early expression of TAg was thought to push kidney cells to replicate the cell’s DNA. This was supposed to give the virus access to the replication machinery it needed. This would mean that TAg would have to be expressed before cells began replicating their DNA.

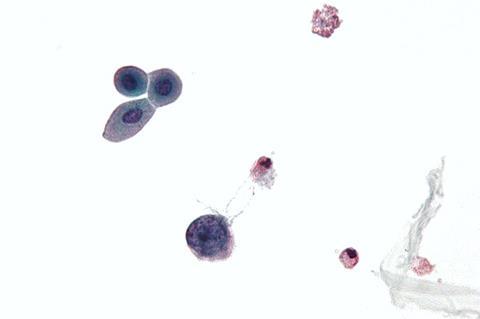

But when Needham, Thompson’s graduate student, performed single-cell cell cycle analysis on BKPyV-infected kidney cells, they were surprised when it showed undetectable TAg expression before the first round of cellular DNA replication. Instead, there was a 100-fold increase in TAg levels as cells finished their first round of DNA replication. The fact that TAg was expressed after DNA replication suggested it was expressed too late to be responsible for driving cells into replicating their DNA.

Intriguing findings

TAg expression and viral replication occurred after the first round of host DNA replication, and TAg expression also depended on the cell’s going through a first round of replication. If Needham inhibited this first round of cellular DNA replication using inhibitors that affected only the cell’s DNA replication but not the virus replication, TAg was never expressed and virus was not produced. However, if he inhibited DNA replication after the first round of replication when TAg was already expressed, host replication was no longer required for maintaining TAg expression or viral production.

Thompson said that “since TAg expression is absolutely required for virus replication, this suggests that inhibiting kidney cell DNA synthesis early after infection could prevent BKPyV replication.”

In other details, the UAB researchers found that, once TAg was expressed, the virus maintained a replicative environment that relied on normal host cell cycle machinery and regulators. It was known that BKPyV infection prevents cell division, resulting in enlarged cellular nuclei filled with DNA from multiple rounds of cellular DNA replication without cell division. More experiments will be required to determine whether the robust TAg expression that occurs after a single round of host DNA replication is what induces the cells to reenter cellular DNA replication and make more copies of the cellular and viral DNA, rather than undergo cell division.

Reducing chances of resistance

This study suggests that inhibitors against the cellular proteins that are required to maintain re-replication would be effective in treating kidney cells that were actively replicating BKPyV without affecting the normal cell cycle. Targeting a host protein reduces the likelihood that viruses would evolve resistance since they do not have genetic control over the drug target.

There is still a lot we do not understand about how BKPyV depends on or promotes these kidney cells to begin replicating DNA, Thompson says. These include understanding how DNA replication is induced after BKPyV infection; if not by early expression of TAg, then how? Furthermore, the mechanisms regulating BKPyV reactivation in human kidneys and the details of the viral life cycle in vivo remain to be answered.

Co-author with Thompson and Needham in the study, “Single-cell analysis reveals host S phase drives large T antigen expression during BK polyomavirus infection,” is Sarah E. Perritt, UAB Department of Microbiology.

Support came from National Institutes of Health grants AI123162, AI178734 and GM008111.

At UAB, Microbiology is a department in the Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine.

No comments yet