Researchers from the Universities of Freiburg and Strasbourg in France have discovered a mechanism that likely contributes to the severity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections and could be a target for future treatments.

Many bacterial species use sugar-binding molecules called lectins to attach to and invade host cells. Lectins can also influence the immune response to bacterial infections. However, these functions have hardly been researched so far.

A research consortium led by Prof. Dr. Winfried Römer from the Cluster of Excellence CIBSS - Centre for Integrative Biological Signalling Studies at the University of Freiburg and Prof. Dr. Christopher G. Mueller from the IBMC - Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology at the CNRS/University of Strasbourg has investigated the effect of the lectin LecB from P. aeruginosa on the immune system.

It found that isolated LecB can render immune cells ineffective: The cells are then no longer able to migrate through the body and trigger an immune response. The administration of a substance directed against LecB prevented this effect and led to the immune cells being able to move unhindered again.The results recently appeared in the journal EMBO Reports.

Barricading the path

As soon as they perceive an infection, cells of the innate immune system migrate to a nearby lymph node, where they activate T and B cells and trigger a targeted immune response. LecB, according to the current study, prevents this migration.

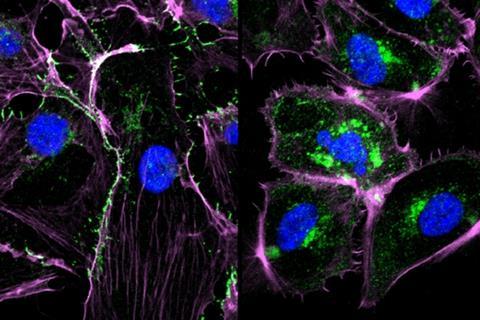

“We assume that LecB not only acts on the immune cells themselves in this process, but also has an unexpected effect on the cells lining the inside of the blood and lymph vessels,” Römer explains. “When LecB binds to these cells, it triggers extensive changes in them.”

Indeed, the researchers observed that important structural molecules were relocated to the interior of the cells and degraded. At the same time, the cell skeleton became more rigid. “The cell layer thus becomes an impenetrable barrier for the immune cells,” Römer said.

Effective agent

To find out if the effect can be prevented, the researchers tested a specific LecB inhibitor that resembles the sugar building blocks to which LecB otherwise binds.

“The inhibitor prevented the changes in the cells, and T-cell activation was possible again,” Mueller said, summarizing the promising results of the current study. The inhibitor was developed by Prof. Dr. Alexander Titz, who conducts research at the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland and Saarland University.

Further studies are needed to determine how clinically relevant the inhibition of the immune system by LecB is to the spread of P. aeruginosa infection and whether the LecB inhibitor has potential for therapeutic application. “The current results provide further evidence that lectins are a useful target for the development of new therapies, especially for antibiotic-resistant pathogens such as P. aeruginosa,” the authors conclude.

No comments yet