When Sean Crosson was a child growing up in rural Texas, he learned about vaccinating cattle against Bang’s disease from his high school agriculture teacher.

Now, Crosson, a Professor Rudolph Hugh Endowed Chair in Michigan State University’s Department of Microbiology, Genetics and Immunology, has been awarded a $2.4 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to study the cause of that very disease, Brucella abortus.

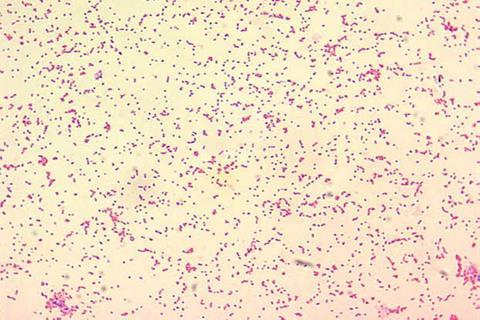

Brucella abortus causes brucellosis disease, which, in addition to being known as Bang’s disease is also referred to as “undulant fever.” No matter the name, this serious condition is highly contagious and causes loss of young, infertility and lameness, predominantly among cattle, bison and swine. The disease can also impact other animals and can be passed on to people. It’s also becoming antibiotic-resistant and is very difficult to treat.

Eradication program

The disease is not a significant problem in livestock in the United States, thanks to an effective U.S. Department of Agriculture eradication program that began in the 1950s. However, there are still populations of wild elk and bison in the Yellowstone National Park area that carry the disease. That’s a problem because when livestock graze on open ranges, they can pick up the disease and introduce it to the rest of the herd.

The disease is a much larger problem in parts of the world with limited resources where people tend to live in close proximity to their livestock.

“Globally, it’s a huge burden on agricultural production. Because you have this reservoir of animals that are infected, it’s a burden on human health. And then it’s a burden on economic productivity for regions where this really, really matters for economic output,” Crosson said. “So, in terms of its impact on global human health and animal health, it’s significant.”

First steps toward a vaccine

The purpose of Crosson’s grant, “Regulation of the Brucella abortus general stress response,” is to conduct fundamental research into the genes and pathways that Brucella abortus uses during infection. The hope is that the new information may eventually be harnessed to create vaccines that prevent disease in wildlife.

READ MORE: Shaping dairy farm vaccination decisions: social pressure and vet influence

READ MORE: Sir Graham Wilson: pioneer in public health, wartime bacteriology and food hygiene

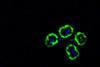

“We have these immune cells, these phagocytic cells, that patrol, and they engulf things that are foreign and dissolve them,” Crosson said. The word “phagocyte” comes from the Greek “phagein,” meaning to eat or devour, and “cyte,” the suffix that denotes “cell” in biology.

Crosson explained that when microbes are engulfed by a phagocyte, they experience a significant increase in acidity along with other harsh chemical changes that can arrest their growth. That type of environmental change is known to scientists as “stress.”

“Microbes have mechanisms to sense that change in the physical or chemical state of the environment and then modify their gene expression to adapt to that change. They change their physiology,” Crosson said.

Stress response

That physiological change Crosson studies is known as a general stress response. It’s Brucella’s stress response that allows it to thwart the phagocytic cells, avoid dissolution and survive in its host.

“This microbe has a toolkit that enables it to squirt out proteins and sort of trick the host cell into trafficking it into a little neutral compartment, and that’s where it replicates,” Crosson said.

“We need vaccines. None of the current vaccines that are used in livestock actually work on elk or bison. So, a long-term goal is we hope that these basic studies will inform the development of better vaccines for animals that pose a threat to livestock.”

Three aims

Crosson’s grant has three specific aims. The first aim focuses on a specific protein that Brucella uses to sense the changes in its world.

It turns out that Brucella has a protein that acts as a photosensor. If you knock out the gene that encodes the photosensor protein, then Brucella can’t infect an animal.

The second aim focuses on a protein called EipB that appears to contribute to the stability of Brucella’s cell envelope.

The cell envelope is a protective layer surrounding a cell. It serves as a barrier between the cell’s inner contents and the external environment.

Falling apart

Crosson explained that if you knock out the gene that encodes EipB and then assault the Brucella with a variety of known envelope stressors, they fall apart. However, the exact mechanisms that cause this are still unknown.

“We used X-ray diffraction and solved the structure of that protein, so we know what it looks like,” Crosson said. “And we have pretty good intuition that it’s doing something that’s sort of brokering or trafficking either lipids or other proteins to maintain the integrity of this barrier. This aim is really focused on trying to understand what that protein is doing.”

Finally, Crosson’s team will investigate the role of two specific noncoding RNAs, named GsrN1 and GsrN2. RNA is comprised of nucleic acids and controls or informs chemical activities within cells. Previous research has shown that while deleting either one of those RNAs doesn’t have a large impact, deleting them both weakens Brucella’s ability to colonize the spleen in a mouse model. Crosson’s team will investigate the specific impact of those small RNAs on Brucella gene regulation.

“We want to understand the why. That’s the basic science of it. But then once you understand it, you can utilize it,” Crosson said. “I do the work because I think it’s important from a human health and AgBio [agricultural biotechnology] perspective.”

No comments yet