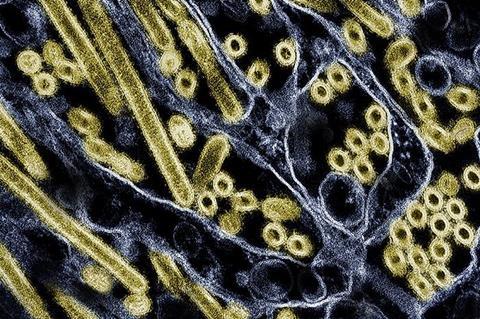

Mice administered raw milk samples from dairy cows infected with H5N1 influenza experienced high virus levels in their respiratory organs and lower virus levels in other vital organs, according to findings published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results suggest that consumption of raw milk by animals poses a risk for H5N1 infection and raises questions about its potential risk in humans.

Since 2003, H5N1 influenza viruses have circulated in 23 countries, primarily affecting wild birds and poultry with about 900 human cases, primarily among people who have had close contact with infected birds. In the past few years, however, a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus called HPAI H5N1 has spread to infect more than 50 animal species, and in late March, the United States reported a viral outbreak among dairy cows in Texas.

To date, 52 cattle herds across nine states have been affected, with two human infections detected in farm workers with conjunctivitis. Although the virus has so far shown no genetic evidence of acquiring the ability to spread from person-to-person, public health officials are closely monitoring the dairy cow situation as part of overarching pandemic preparedness efforts.

Raw milk

To assess the risk of H5N1 infection by consuming raw milk, researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory fed droplets of raw milk from infected dairy cattle to five mice. The animals demonstrated signs of illness, including lethargy, on day 1 and were euthanized on day 4 to determine organ virus levels. The researchers discovered high levels of virus in the animals’ nasal passages, trachea and lungs and moderate-to-low virus levels in other organs, consistent with H5N1 infections found in other mammals.

In addition to the mice studies, the researchers also tested to determine which temperatures and time intervals inactivate H5N1 virus in raw milk from dairy cows. Four milk samples with confirmed high H5N1 levels were tested at 63 degrees Celsius (145.4 degrees Fahrenheit) for 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes, or at 72 degrees Celsius (161.6 degrees Fahrenheit) for 5, 10, 15, 20 and/or 30 seconds. Each of the time intervals at 63℃ successfully killed the virus. At 72℃, virus levels were diminished but not completely inactivated after 15 and 20 seconds.

The authors emphasize, however, that their laboratory study was not identical to large-scale industrial pasteurization of raw milk and reflect experimental conditions that should be replicated with direct measurement of infected milk in commercial pasteurization equipment.

In a separate experiment, the researchers stored raw milk infected with H5N1 at 4℃ (39.2 degrees Fahrenheit) for five weeks and found only a small decline in virus levels, suggesting that the virus in raw milk may remain infectious when maintained at refrigerated temperatures.

Commercial milk supply

To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration concludes that the totality of evidence continues to indicate that the commercial milk supply is safe. While laboratory benchtop studies provide important, useful information, there are limitations that challenge inferences to real world commercial processing and pasteurization.

The FDA conducted an initial survey of 297 retail dairy products collected at retail locations in 17 states and represented products produced at 132 processing locations in 38 states. All of the samples were found to be negative for viable virus. These results underscore the opportunity to conduct additional studies that closely replicate real world conditions.

FDA, in partnership with USDA, is conducting pasteurization validation studies – including the use of a homogenizer and continuous flow pasteurizer. Additional results will be made available as soon as they are available.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, funded the work of the University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers.

No comments yet