In multiple sclerosis (MS), antibodies to the common Epstein-Barr virus can accidentally attack a protein in the brain and spinal cord. New research shows that the combination of certain viral antibodies and genetic risk factors can be linked to a greatly increased risk of MS. The study has been published in the journal PNAS and led by researchers at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, and Stanford University School of Medicine, USA.

An estimated 90 to 95 percent of adults are carriers of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and have formed antibodies against it. Many become infected as children with few or no symptoms, but in young adults, the virus can cause glandular fever. After infection, the virus remains in the body in a dormant (latent) phase without active virus production.

Attacking a protein in the brain

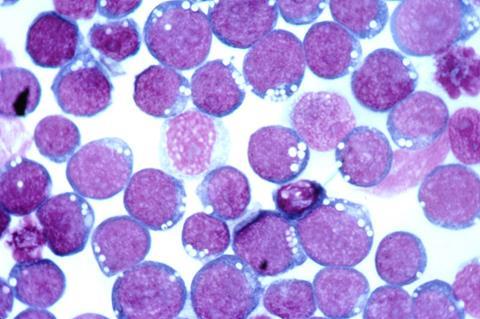

Everyone affected by the neurological disease MS, where the immune system attacks the brain and spinal cord, is a carrier of EBV. However, the mechanisms behind the association are not fully understood.

Now, researchers at Karolinska Institutet and Stanford Medicine have confirmed that antibodies to an EBV protein called EBNA1 can inadvertently react with a similar protein in the brain called GlialCAM, which probably contributes to the development of MS. The new study also shows how different combinations of antibodies and genetic risk factors for MS contribute to the risk increase.

READ MORE: A surprising link between Crohn’s disease and the Epstein-Barr virus

READ MORE: Scientists find weak points on Epstein-Barr virus

“A better understanding of these mechanisms may ultimately lead to better diagnostic tools and treatments for MS,” says Tomas Olsson, professor of neurology at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, who led the research there with professor Ingrid Kockum and assistant professor Olivia Thomas.

The researchers analysed blood samples from 650 MS patients and 661 healthy people. They compared the levels of antibodies directed against the viral protein EBNA1 and the levels of misdirected antibodies against GlialCAM and two other proteins in the brain, ANO2 and CRYAB, which are also similar to EBNA1.

Increased levels of antibodies

Elevated levels of all these antibodies were detected in people with MS. High antibody levels in combination with a genetic risk factor for MS (HLA-DRB1*15:01) were associated with a further increase in risk. The absence of a protective gene variant (HLA-A*02:01) in combination with any of the antibodies against proteins in the brain was also associated with a strong increase in risk.

“The new findings provide another piece of the puzzle that adds to our understanding of how genetic and immunological factors interact in MS,” says Lawrence Steinman, professor of neurology at Stanford Medicine, who led the research there with William Robinson, professor of immunology and rheumatology, and Tobias Lanz, assistant professor of immunology and rheumatology.

Biomarker potential

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet now plan to analyse samples collected before MS disease development to see when these antibodies appear.

“If they are already present before the onset of the disease, they may have the potential to be used as biomarkers for early diagnosis,” says Tomas Olsson.

No comments yet