A total of seven individuals worldwide (two patients in Berlin and patients in London, Düsseldorf, New York, City of Hope and Geneva) are considered likely to have been cured or to be in long-term remission of HIV infection after receiving a bone marrow transplant to treat blood cancer.

Romuald, the Geneva patient, who is being monitored at Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), is the only one to have experienced HIV remission following a bone marrow transplant without the CCR5-delta 32 mutation. This rare genetic mutation is known to make CD4 cells naturally resistant to HIV.

READ MORE: New HIV reporter model: Visualizing HIV viral dynamics in cells with dual fluorescence

READ MORE: Study outlines world’s third successful cure of HIV infection after stem cell transplantation

The case published in Nature Medicine was part of a study coordinated by Professor Alexandra Calmy, MD, PhD, Director of the HIV/AIDS Unit in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) and Vice-Dean in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Geneva (UNIGE), and Professor Asier Sáez-Cirión, Head of the Viral Reservoirs and Immune Control Unit at the Institut Pasteur (Paris), in collaboration with the Institut Cochin and the IciStem consortium.

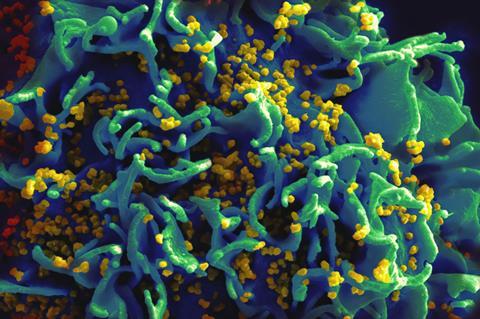

Cells susceptible

Unlike in previous cases, where the presence of the CCR5-delta 32 mutation seems to have played a decisive role in the HIV outcome, the study published shows that the Geneva patient’s cells remain susceptible to HIV infection. Despite this, the virus remains undetectable in the patient nearly three years after antiretroviral treatment was stopped.

By closely monitoring the patient over an extended period, the scientists were able to demonstrate a progressive reduction in the viral reservoir following the transplant. Virus-carrying cells capable of multiplying, which could be easily detected before the transplant, were no longer detectable in the most recent analyses.

The article, published in Nature Medicine, presents these results together with the hypotheses that the UNIGE, HUG and Institut Pasteur teams are working on to try to explain why this patient has entered remission. The presence of innate immune cells with strong anti-HIV potential could prevent a rebound in the virus even if there may still be some infected cells in the body. The immunomodulatory treatment that the patient is receiving to control graft-versus-host reactions, which he has repeatedly experienced since the transplant, could also help prevent viral reactivation.

Finally, these graft-versus-host reactions may have led to the viral reservoir being eliminated so effectively that the CCR5-delta 32 mutation is no longer necessary as no virus capable of multiplying remains in the body. These hypotheses open up promising avenues for research aimed at achieving remission for HIV infection.

No comments yet