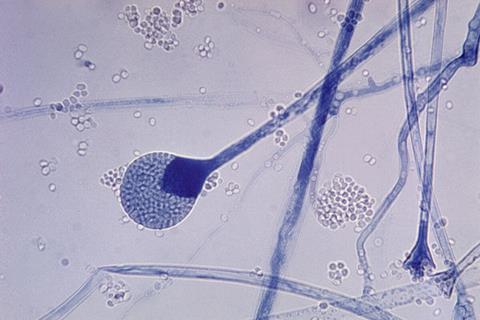

For people with weakened immune systems, common molds lurking in the environment — in the soil, along damp walls or on a forgotten apple — can cause dangerous infections deep inside the body. These invasive mold infections can quickly become fatal without treatment, yet they are difficult to diagnose without invasive procedures such as a tissue biopsy.

Now, a blood test developed at Stanford Medicine offers a safer, faster way to diagnose invasive mold disease. In a new study, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, researchers found that the blood test, which detects genetic material from mold, could replace invasive tests in most cases.

“We all breathe in a couple thousand mold spores a day,” said Niaz Banaei, MD, professor of pathology and of medicine, and the study’s senior author. “While our immune systems are intact, nothing happens to us.”

Risk factors and diagnosis

But when immune defenses are compromised, such as in transplant patients on immunosuppressants and patients undergoing chemotherapy, molds can set up shop inside the body, most often in the lungs. Banaei estimates that 5% to 10% of these patients develop invasive mold disease.

These rapidly progressing infections often appear as lesions on a CT scan.

READ MORE: Fungal infection acquired during surgery led to death and brainstem, blood supply injuries

READ MORE: Global review charts lethal impact of fungal infection after lung disease

The conventional way to diagnose these infections requires obtaining a sample of the mold, either from tissue biopsy or bronchoalveolar lavage, in which a scope is inserted into the lungs to wash out the airways with saline solution. The mold sample is then identified in the lab to determine the appropriate antifungal medications.

“A lot of immunocompromised patients are not stable enough to undergo these invasive procedures,” Banaei said. “So they can’t get a precise diagnosis.” That could mean a delay in effective treatment.

Detecting mold DNA

For several years, Banaei and colleagues have been developing a non-invasive alternative — a blood test that can detect tiny fragments of mold DNA that have been shed into the bloodstream. The underlying technique, known as cell-free DNA polymerase chain reaction, sometimes referred to as a liquid biopsy, has shown promise in detecting other types of infections, as well as cancer. The new blood test for mold infections debuted at Stanford Health Care in late 2020.

The researchers optimized the protocols for collecting blood samples, extracting DNA and accurately detecting a range of common mold species. The test was then ready for a head-to-head comparison with conventional tests.

Test evaluation

In the new study, the research team reviewed 506 cases in which a patient with suspected mold disease underwent both the blood test and an invasive test within about a week. The majority of patients were immunocompromised.

When the test results were evaluated based on the standard diagnostic criteria for invasive mold disease, both tests returned the same diagnosis 88.5% of the time.

“This study is evidence that you don’t need to follow up with an invasive test,” Banaei said. “The great majority of times, you can expect the two results to be concordant.” That means most patients can be spared the risk of an invasive procedure.

The blood test was more likely to miss mold infections in the sinuses or in the limbs, so suspected infections in these locations should still warrant tissue biopsy, he said.

Critically, the new test allows for faster diagnosis and treatment, which has been shown to improve patient outcomes. The turnaround time for the blood test is a single day, whereas the invasive procedures often take several days to weeks to schedule and to return results.

“We can speed up the diagnosis and not have to wait for a scheduled surgery or bronchoscopy,” Banaei said. “The second you suspect an infection, you can order this test and get an idea of what the patient has.”

Only at Stanford

For now, Stanford Health Care is the only institution that offers the new mold test. Demand for the test has increased steadily since it became available, with about 3,000 tests currently ordered per month, according to Banaei. “It definitely has become the initial go-to test when we suspect a fungal infection,” he said.

Though the test in its current form requires many laboratory resources, robotics and trained staff, Banaei is working with companies to commercialize the test. The goal is to create a stand-alone instrument that could automate the test. “That could change the game by making such technology available for everybody,” Banaei said.

His team is also developing cell-free DNA polymerase chain reaction tests for other difficult-to-diagnose infections. In fact, their original target was tuberculosis, the No. 1 infectious cause of death around the world, with a third of cases undiagnosed. A high-performing blood test for tuberculosis has proved more elusive, Banaei said. “But we haven’t given up.”

No comments yet