Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received a $12 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study how vaccines trigger long-lasting immune responses. The work may inform the design of new, more protective vaccines for respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 and influenza.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, we witnessed the development of effective vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in record time. But we also watched their effectiveness wane in a matter of months. Our work aims to understand how to design vaccines that trigger enduring immunity against rapidly mutating respiratory viruses.” said Ali Ellebedy, PhD, the Leo Loeb Professor of Pathology & Immunology at WashU Medicine.

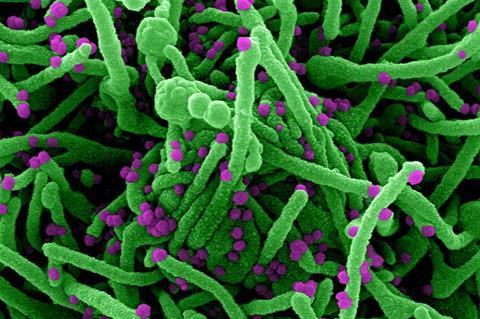

READ MORE: Researchers develop promising Lassa fever vaccine

READ MORE: Campylobacter jejuni-specific antibody gives hope to vaccine development

”Waning immunity is not unique to COVID-19 vaccines. For five decades, the flu vaccine has required an annual update. Antibodies that help clear the influenza virus are almost gone within six months to a year after infection or vaccination, and the virus is adept at rapidly changing to escape immune protection, rendering the previous year’s vaccine ineffective.” Ellebedy explained.

But other vaccines maintain immunity long-term or indefinitely. The smallpox vaccine offered strong protection that helped eradicate the virus, rendering routine immunization unnecessary. Vaccines against polio, chickenpox, measles, mumps and rubella, among others, confer lifelong immunity. Some vaccines require a periodic booster that reeducates the immune system how to respond to a threat.

Lifelong protection is the gold standard

“Lifelong protection is the gold standard in vaccine development,” Ellebedy said. “We have an opportunity to learn from successful vaccine events, which have stopped the spread of pathogens or even eliminated them. We need to understand what such vaccines are doing to the immune system that the flu and COVID-19 vaccines are not able to do.”

Ellebedy is leading the newly funded study with co-principal investigator Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine, and clinical lead Rachel M. Presti, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine. As co-directors of the Center for Vaccines & Immunity to Microbial Pathogens at WashU Medicine, funded in part by Andrew M. and Jane M. Bursky, the trio has built the infrastructure that will help them define the factors that enable enduring immunity after vaccination.

The researchers will immunize study participants against influenza viruses and SARS-CoV-2 and examine B and T cells – subsets of immune cells involved in fighting pathogens – in the blood, draining lymph nodes and bone marrow. Induced immune responses after a flu or COVID-19 vaccine will be compared with responses after systemic vaccines that trigger effective, lifelong immune responses.

More effective vaccines needed

Respiratory viruses infect the mucus-secreting membranes of the respiratory tract, including the nose, sinuses, throat, airways and lungs. The researchers also will study the durability of the immune response at the infection site of study participants who recover from COVID-19 or the flu, compared with the systemic immune responses in the blood of the same participants. Such knowledge may help guide the design of nasal vaccines for respiratory viruses.

Their work adds to other major pandemic preparedness research projects at WashU Medicine. Recently, Diamond and Sean Whelan, PhD, the Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor and head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology, were awarded two grants totaling more than $90 million over the next three years from NIAID to design rapid responses to pathogens such as chikungunya, dengue and parainfluenza viruses.

“Respiratory viruses threaten world health,” said Diamond, also a professor of molecular microbiology and of pathology & immunology. “To prevent viral outbreaks, we need more effective vaccines. Studying human immune responses after vaccination or infection will help untangle the immunological shortcomings of current vaccines and identify the factors that are responsible for comprehensive and long-lasting immunity against disease.”

No comments yet