Public sector data associated with health are a highly valuable resource, yet in practice data-sharing poses multiple challenges. Dr Nicola Holden, from AMI’s One Health Scientific Advisory Group, explores the murky morass of big data.

The use of DNA sequence-based data is integral to our understanding, control and application of microbes. Indeed, it is hard to imagine any aspect of microbiology without drawing on this type of data. This is true for all microbes, whether derived from single organisms or communities, from cultures or obtained directly.

Sequence-based data describes what the organism is, how it can function and interact with hosts or habitats. Its provision is relatively straight-forward: generate the nucleic acid content, sequence for the chosen targets, perform the analysis, and deposit into a common repository.

Following this basic pipeline opens the sequence as a resource for all, complying with need for openly accessible data. In turn, that provides a wealth of information, used in a myriad of ways, each time acting as an invaluable multiplier from the original investment.

An embarrassment of riches

Glancing through any sequence repository displays a staggering volume of data, with no signs of slowing down. As the technology and our imagination develop, microbes are described that even only a decade ago would have seemed unfeasible. This wealth of data supplies material for references or in comparisons, for virtually any situation.

READ MORE: Mobile phone data helps track pathogen spread and evolution of superbugs

In addition to storage, sequence data repositories form the essential function of permitting accessibility to the data. That has opened remarkable opportunities that we have become accustomed to, whether the real-time sequencing that was so instrumental in control and treatment during the Covid-19 pandemic as the virus evolved, or novel drug discovery increasingly mined using sophisticated machine learning approaches. So where do any problems lie?

Re-use of data

Despite this rich seam of data, difficulties can arise in re-use of genomics and especially meta-genomics data. Openly accessible data needs to comply with the FAIR guidelines that make it Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable.

However, there can be genuine challenges for sharing sequences and associated sample data, compounded for protected or sensitive samples. The issue is relevant to any sequence-based data and is especially pertinent as an emerging challenge for microbiome sequence sets.

It is inherently linked to the biological collections and resources collected to generate the sequence-based information, not least because the samples need to be properly described, but also for samples archived in long-term storage.

The two main, interlinked issues:

(i) Insufficient contextual metadata to enable downstream questions to be addressed. Without full enough descriptions of the samples, the initial investment to generate the data is only ever of use to the primary researcher who obtained it. Yet sequence data is economically expensive to obtain, and inefficient to maintain as ‘redundant’ electronic records, and as any associated biological resource.

(ii) Data with direct, or potential sensitives that restrict its access and impede sharing & re-use. Frameworks to handle this issue aren’t always in place or are insufficient for microbe-associated sequences.

Potential solutions

There is a way through this apparent impasse, to avoid the trap of generating more data simply because the information that is available can’t be re-used properly. This takes consideration of the steps required for collecting data and then for sharing it, and enlisting those with interest and influence to find the best path.

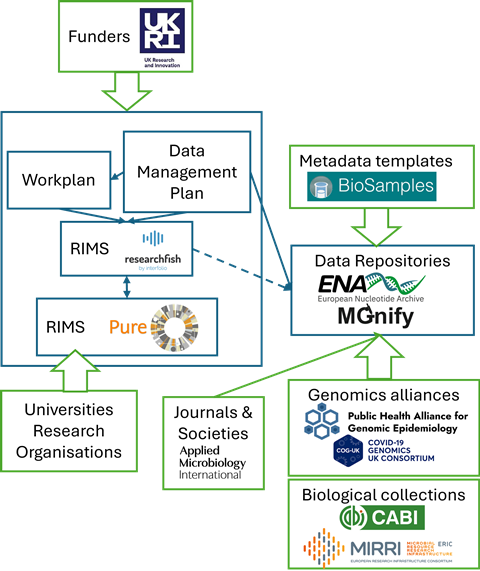

In collecting data for research projects, Data Management Plans describe the type of data, where it is stored and how it can be accessed. They could provide a solution by acting as a pivotal point between generation and release.

The funding organisations who make the initial long-term investment need to play a role, as can universities and research organisations with their own research information management system (RIMS). For subsequent publication, journals and microbiology societies who already have a requirement for describing sequence-based data and depositing or linking primary datasets, can provide suggestions.

Adding to repositories

Depositing data into repositories requires metadata to describe the sample information. However, provision of sufficient metadata is seen as a barrier, whether perceived or real. Sequence and collection repositories can help for better use of templates, as well as simplification and / or automation for uploading the data.

Finally, better routes are required for accessing data with explicit protections, such as those from public health or commercial sources. Reference laboratories and governmental agencies can play a central advisory role here. Genomics and sample collections alliances together with trusted environments that hold protected data already know how to handle real-world samples, with experience of urgent needs, dealing at scale and speed.

All parties can also help to pre-empt new issues. For example, some data may have sensitivities that only become apparent from secondary use, and were not considered during primary acquisition. This could be metagenomics data with pathogen or biological hazard sequence data that was not uncovered in the original analysis.

By working in partnership, the balance can be tipped toward enhancing secondary use of existing sequence-based data, adding value, efficiency and sustainability.

Nicola Holden, Scotland’s Rural College (nicola.holden@sruc.ac.uk), and Scottish Government (nicola.holden@gov.scot)

This article follows publication and panel discussion from the KTN One Health Microbiome meeting (Liverpool, 10-11 Sept 2024), and is directly related to the UKRI-funded policy fellowship with Scottish Government (ES/Y004434/1) plus the BBSRC-funded BBR project the UK Crop Microbiome Cryobank (BB/T019484/1). Many of these issues and potential solutions were outlined in a recent opinion piece published in AMI’s Journal of Applied Microbiology.

No comments yet