Of the trillions of bacteria that live in your gut, many cooperate to digest food, support our immune systems, and keep us healthy. But these microbes are also locked in fierce competition—fighting for space, nutrients, and survival.

Bacteria have engaged in this battle for millennia, evolving to alter their own ecological communities. But until now, studies of microbial warfare have mostly focused on the harmful bacteria we associate with disease – distant relatives of the friendly bacteria that occupy our gut.

READ MORE: Researchers uncover control mechanisms of polysaccharide utilization in gut bacterium

READ MORE: A healthy diet is key to a healthy gut microbiome

The lab of Andrew Goodman, the C.N.H. Long Professor of Microbial Pathogenesis and Director of the Microbial Sciences Institute(Link is external) at Yale’s West Campus, has undertaken a deep dive into the inner workings of this ‘microbial arms race’, revealing an elegant strategy that gut microbes use to stay a step ahead of their neighbors.

Their findings appear in Cell Host & Microbe.

Bacterial disruptor

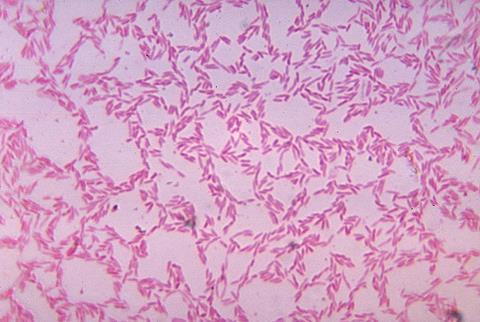

First author Bentley Lim, Goodman, and the research team found that common, friendly gut bacteria of the genus Bacteroides injects a protein into its rivals that disrupts how targeted bacteria fold their proteins, breaking them down from the inside.

All cells, including bacteria, rely on protein-folding systems to stay alive. The process ensures that proteins form the right shapes to do their jobs.

The Goodman lab reports that the Bacteroides protein Bte1 hijacks this process in rival cells, turning their protein-folding systems into potent anti-folding machines that actively tangle proteins together into useless clumps.

This weakens the targeted bacteria, making them more vulnerable to stress, especially in inflamed gut environments. In the DNA of human gut microbial communities, the authors found evidence that some microbes have developed ways to inactivate Bte1, with Bte1 evolving in response to avoid these evasion strategies.

Outsmarting the competition

“The idea that there are good and bad microbes in our gut is only part of the picture. Our findings show that regular bacteria compete in the most intricate and elaborate ways to outsmart their rivals,” Lim explains.

Inhibiting protein-folding systems is an actively pursued therapeutic strategy in cancer and Alzheimer’s disease research. Beyond its implications for understanding our microbiomes, the Goodman lab’s work raises intriguing possibilities that our own gut microbes could teach us new ways to target protein folding in human disease.

Additional collaborators included the laboratories of Xiang Gao, Shandong University, and David J. Gonzalez, University of California San Diego.

No comments yet