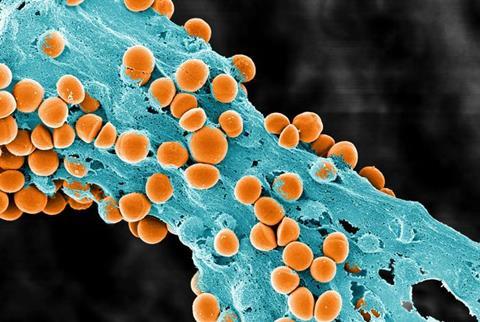

From plaque sticking to teeth to scum on a pond, biofilms can be found nearly everywhere. These colonies of bacteria grow on implanted medical devices, our skin, contact lenses, and in our guts and lungs. They can be found in sewers and drainage systems, on the surface of plants, and even in the ocean.

“Some research says that 80% of infections in human bodies can be attributed to the bacteria growing in biofilms,” says Aawaz Pokhrel, Georgia Institute of Technology Ph.D. student and lead author of a groundbreaking new study that uses physics to investigate how these biofilms grow.

READ MORE: Arrangement of bacteria in biofilms affects their sensitivity to antibiotics

READ MORE: Scientists deploy synthetic amyloids to figure out ways of targeting biofilms

The paper, “The Biophysical Basis of Bacterial Colony Growth,” was published in Nature Physics this week, and it shows that the fitness of a biofilm — its ability to grow, expand, and absorb nutrients from the medium or the substrate — is largely impacted by the contact angle that the biofilm’s edge makes with the substrate. The study also found that this geometry has a bigger influence on fitness than anything else, including the rate at which the cells can reproduce.

Big surprise

“That was the big surprise for us,” says corresponding author Peter Yunker, an associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Physics. “We expected that the geometry would play an important role, and we thought that figuring out exactly what the geometry is would be important for understanding why the range expansion rate, for example, [the rate at which the biofilm spreads across the surface over time] is constant. But we didn’t start the project thinking that geometry would be the single most important factor.”

Understanding how biofilms grow — and what factors contribute to their growth rate — could lead to critical insights on controlling them, with applications for human health, like slowing the spread of infection or creating cleaner surfaces. “What got me excited was this opportunity to use physics to learn about complex biological systems,” Pokhrel, who is also a Ph.D. student in Yunker’s lab, adds. “Especially on a project that has so many applications. The combination of the importance for human health and exciting research was really intriguing for me.”

New method

While biofilms are ubiquitous in nature, studying them has proven difficult. Because these “cities of microorganisms” are comprised of tiny individuals, scientists have struggled to image them successfully.

That changed in 2015, when Yunker began wondering if interferometry, a commonly used imaging technique in physics and materials science, could be applied to biofilms. “Given my background in physics, I was familiar with its use in materials applications,” Yunker recalls. “I thought applying this technique more broadly might be interesting, because we know from decades of physics that surface interfaces contain a lot of information about the processes that create them.”

The technique proved to be simple, effective, and time-efficient, providing nanometer-scale resolution of bacterial colonies. “It allows us to essentially get a picture of the topography — the shape of the surface of the bacterial population — with super-resolution,” Yunker adds.

Biofilm experiments

Leveraging interferometry, the team began conducting new biofilm experiments, investigating how colonies’ shapes changed over time. Co-first author Gabi Steinbach, formerly a postdoctoral scholar in Yunker’s lab and now a scientific research coordinator at the University of Maryland, noticed that every colony had a specific shape when it was small: a spherical cap, like a slice from the top of a sphere, or a droplet of water. It’s a shape that shows up often in physics, and that sparked the team’s interest.

“A spherical cap in physics is very interesting, because it is a surface-minimizing shape,” Pokhrel adds. “I was curious why a biological material was growing in this shape, and we started wondering if there was some physics to it – perhaps geometry was involved. And that made us think that maybe we could develop a model. And that got me really excited.”

Mathematical mystery

However, the researchers soon hit a roadblock. “While we could see that the colonies were spherical caps at first, they would deviate from that shape as they grew,” Pokhrel says. “And the shape that they grew into was difficult to describe with existing spherical cap geometry.”

“The middle didn’t grow as quickly as it should to keep the spherical cap shape, and we wanted to connect all of this to the range expansion [the rate at which the colony spread across a surface],” Yunker adds. “But we knew that somehow, geometry was playing a very important role.”

Finally, Thomas Day, a former graduate student in Yunker’s lab, now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Southern California, and one of the authors of the paper, suggested a quirky problem of geometry called the napkin ring problem.

Napkin ring problem

“As soon as we started to think about the napkin ring problem, we were able to start developing a mathematical toolkit,” Yunker says, though the solution wasn’t effortless. “We couldn’t find anyone who had ever looked at a spherical cap napkin ring before, because the application is very rare.”

Pokhrel, alongside two co-authors, was responsible for working out the geometry. He discovered that the cells grew exponentially at the edge of the shape, expanding further onto the medium, while the cells in the middle grew upward, creating a shape not unlike an egg in a frying pan — if the egg white was expanding outwards, while the yolk was only growing taller.

This was the breakthrough discovery: Because the cells at the middle were only contributing to the biofilm’s height, the team only needed to account for how many cells were at the edge of the biofilm, and the shape they needed to be in to grow and spread.

Contact angle

After incorporating their findings into a mathematical model, the team found that the contact angle was the most important factor: the angle that the very edge of the biofilm made when it touched the surface it was growing on. That single geometric quality is even more important to a biofilm’s growth than the rate at which it can reproduce cells.

Overall, the project took more than three years, from conception to publication. “Aawaz really made an incredible effort seeing this work through,” Yunker says. “It was many years and many, many experiments. But the finished product is 100% worth it.”

The team hopes the research will pave the way for future studies, which could lead to applications like controlling biofilm growth to help prevent infections.

Competition experiments

“Going forward, there are still a lot of research avenues,” Pokhrel says. “For example, looking at competition experiments between biofilms — do taller colonies change their contact angle so that they can spread faster? What role does this geometry play in competition?”

“Biology is complex,” Yunker adds. In nature, the surface a biofilm grows on may not be as consistent as a laboratory surface, and colonies may have different mutations or may consist of more than one species. And while the model is based on how biofilms behave in a controlled lab environment, it’s a critical first step in understanding how they may behave in nature.

No comments yet