An international team of researchers, led by scientists from Tel Aviv University, has discovered that the pathogen responsible for the mass deaths of sea urchins along the Red Sea coast is the same one responsible for mass mortality events among sea urchins off the coast of Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean.

This finding raises fears that the pathogen – a waterborne ciliate - could spread further, to the Pacific Ocean. The researchers warn that this is a highly aggressive global pandemic, and are now spearheading an international effort to track the disease and preserve sea urchins, which play a crucial role in the health of coral reefs.

The study, led by Dr. Omri Bronstein from the School of Zoology at Tel Aviv University’s Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, was published in the prestigious journal Ecology.

Ecological disaster

“This is a first-rate ecological disaster,” explains Dr. Bronstein. “Sea urchins are vital to the health of coral reefs. They act as the ‘gardeners’ of the reef by feeding on algae, preventing it from overgrowing and suffocating the coral, which competes with algae for sunlight. In 1983, a mysterious disease wiped out most of the Diadema sea urchins in the Caribbean. Unchecked, the algae there proliferated, blocking sunlight from the coral, and the region shifted from a coral reef ecosystem to an algae-dominated one. Even 40 years later, the sea urchin population — and consequently the reef — has not recovered.”

The research team said: “This is an extremely violent global pandemic. The Caribbean, Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean are critical regions for the world’s coral reefs, and mortality rates for sea urchins in these areas are very high — over 90 per cent. As of now, we have no evidence of this pathogen in Pacific Ocean sea urchins (where some of the world’s largest and most vital coral reefs are located), but this is something we are actively investigating.”

IDing the culprit

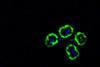

In 2022, the disease reemerged in the Caribbean, targeting the surviving sea urchin populations and individuals. This time, armed with advanced scientific and technological tools to collect and interpret the forensic evidence, researchers at Cornell University successfully identified the pathogen as a ciliate Scuticociliate parasite. A year later, in early 2023, Dr. Bronstein was the first to identify mass mortality events among long-spined sea urchins, a close relative of the Caribbean Sea urchins, in the Red Sea.

READ MORE: Microscopic sea urchin killer spreads to new species and regions

READ MORE: Massive Caribbean sea urchin die-off caused by unicellular parasite

“Until recently, this was one of the most common sea urchins in Eilat’s coral reefs — the familiar black urchins with long spines,” says Dr. Bronstein. “Today, this species no longer exists in significant numbers in the Red Sea. The event was extremely violent: within less than 48 hours, a healthy population of sea urchins turned into crumbling skeletons. In some locations in Eilat and the Sinai, mortality rates reached 100 percent. In follow-up research, we demonstrated that the Caribbean pathogen was the same one affecting populations in the Red Sea.”

Global event

Now, using genetic tools, Dr. Bronstein and his international colleagues have shown that the same ciliate parasite is responsible for similar mortality events off the coast of Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean. “This is the first genetic confirmation that the same pathogen is present in all these locations,” he says.

“Now it’s a global event, a pandemic. The Caribbean, Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean are critical regions for the world’s coral reefs, and mortality rates for sea urchins in these areas are very high — over 90 per cent. As of now, we have no evidence of this pathogen in Pacific Ocean sea urchins, but this is something we are actively investigating.

“Although we’ve developed genetic tools for the specific identification of the pathogen, it’s difficult to monitor such rapid extinction events in the vast underwater environment. We are terrestrial creatures, and some reefs are located in deep or remote areas. If we miss the mortality event by even a couple of days, we might find no trace of the extinct population.”

International network

To track the progression of the pandemic, Dr. Bronstein has established an international network of collaborators. He provides them with alerts about the likelihood of mortality events in their regions and sends them the necessary equipment to sample and preserve affected sea urchins for comparison with samples from other locations. These kits are then sent back to the laboratory at Tel Aviv University.

“For populations that are already infected, we really have no tools to help them,” says Dr. Bronstein with regret. “There is no Pfizer or Moderna for sea urchins — not because we don’t want one, but because we simply can’t treat them underwater. Our focus must be on two entirely different tracks.

”The first is prevention. To prevent further spread of the pandemic, we need to understand why it erupted here and now. We’ve developed two hypotheses for this. The first is the transportation hypothesis — that the pathogen from the Caribbean was transported by humans to new and distant regions after being carried in the ballast water of ships, infecting sea urchins in the Red Sea before spreading to the Western Indian Ocean.

Cargo ships

”Incidentally, if this hypothesis is correct, we would expect to see mortality events in West Africa as well — as many cargo ships from the Caribbean stop there on their way to the Mediterranean and then through the Suez Canal to the Red Sea. Indeed, just in the past few weeks, we’ve discovered widespread mortality events in West Africa, as we predicted, and we’ve managed to obtain a limited number of samples collected during these events, which we are currently analyzing in the lab.

”If ships are indeed the source of the spread, then we could think of mitigation strategies. It’s not simple, and ships will never be completely sterile, but there are measures we can take. The second possibility is even more concerning: that the pathogen has always been present, and climatic changes have triggered its virulence and outbreak. That’s a challenge of an entirely different magnitude, one that we, as marine biologists, have very limited means to address.”

Breeding nucleus

In parallel with global efforts, Dr. Bronstein has recently established a breeding nucleus for the affected sea urchins at the Israel Aquarium in Jerusalem, in collaboration with the Biblical Zoo and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. This breeding population will serve as a reserve to restore affected populations and advance research into infection mechanisms and possible treatments.

“The pathogen is transmitted through water, so even sea urchins raised for research purposes in aquariums at the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences and the Underwater Observatory in Eilat became infected and died. That is why we established a breeding nucleus with the Israel Aquarium, whose aquariums are completely disconnected from seawater. We genetically test the urchins transferred to the nucleus to ensure they are not carriers of the disease and that they genetically belong to the Red Sea population, enabling us to rehabilitate the population in the future. At the same time, we are using them to develop sensitive genetic tools for early disease detection from seawater samples — essentially creating ‘underwater COVID tests’ for sea urchins.”

No comments yet