Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), the cause of the common cold sore, can spread into the central nervous system and preferences for certain parts of the brain. Study results published today in the Journal of Virology are among the first to recognize how this common virus infiltrates the brain, leading to a better understanding of how HSV-1 may trigger neurological diseases.

READ MORE: Scientists discover viral trapdoor blocking HIV and herpes

READ MORE: What enables herpes simplex virus to become impervious to drugs

“Recently, this common virus has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, but no clear route of central nervous system invasion has been established,” says Christy Niemeyer, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and co-first and corresponding author. “Identifying how HSV-1 can get into the brain and what brain regions are vulnerable is key in understanding how it initiates disease.”

Virus travels within the brain

Once HSV-1 enters the brain, researchers also wanted to determine if the virus migrates at random or to specific areas. They were able to map where and how the virus travels within the brain and infects critical brain regions that control many vital functions, such as the brain stem, which controls sleep and movement. Researchers also found HSV-1 in regions of the brain that produce serotonin and norepinephrine, as well as the hypothalamus, a critical center of appetite, sleep, mood, and hormonal control within the brain.

“Even though the presence of HSV-1 is not causing full-blown encephalitis in the brain, it can still affect how these regions function,” says Niemeyer.

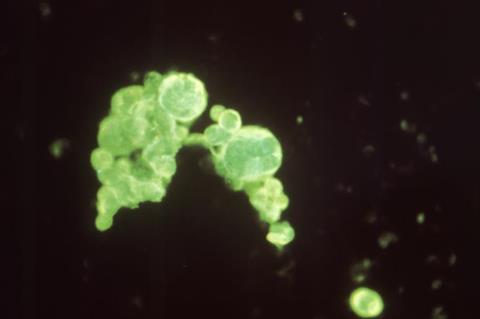

Niemeyer and coauthors also show how HSV-1 interacts with the brain’s key immune cells; microglia. They found that microglia became “inflamed” when interacting with HSV-1, but in some brain regions, inflamed microglia persisted even after the virus was no longer detected.

“Identifying the role of microglia provides helpful clues to the consequences of HSV-1 infection, and how it triggers neurological diseases,” says Niemeyer. “persistently inflamed cells can lead to chronic inflammation, a known trigger for a number of neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. This research offers important takeaways in better understanding how viruses interact with overall brain health as well as the onset of pervasive neurological diseases.”

No comments yet