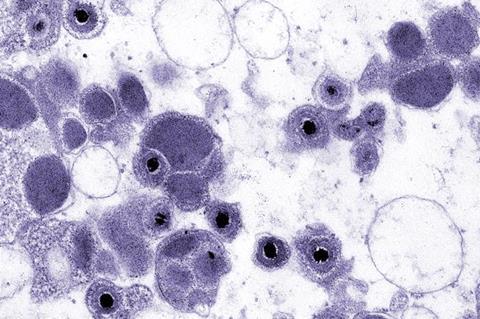

Some viruses can be dormant throughout a person’s life and cause no harm but become dangerous when the immune system is weakened. One of such viruses is human cytomegalovirus (CMV) - harmless to the general public but life-threatening to patients with a supressed immune system.

“Patients undergoing bone marrow transplantations have their blood and immune system fully replaced by that of the donor,” explains Dr. Julien Subburayalu, a clinical scientist in the Sieweke group at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD), one of the leading authors of the study, published in EMBO Molecular Medicine.

”In the first months after transplantation they are defenseless. They can either catch CMV or have virus reactivated that was dormant in the patient. At the moment, there is no ideal treatment. The available ones work in a limited way or can cause severe side effects such as kidney failure, liver failure, deafness, sepsis, and others,”

Unusual approach

Teaming up with Dr. Marc Dalod, an expert on CMV immunity, the researchers led by Prof. Sieweke took an unusual approach. Instead of targeting the virus with antiviral treatments, they focused on strengthening the immune system to fight the virus on its own.

“So far, antiviral treatments focused on targeting specific viruses, either through vaccination or by drugs that work on viral molecular machinery,” mentions Dr. Marc Dalod, group leader at the Centre d’Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy (CIML) and author of the study.

“Our method intervenes at the level of patient’s blood stem cells to boosts general antiviral defenses. It’s ideal as a prophylactic or a general intervention strategy in immunosuppressed individuals,” says Prof. Michael Sieweke, Alexander von Humboldt Professor and research group leader at the CRTD and CIML.

Small but mighty

The new approach focuses on the cytokine known as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, CSF1). It’s a small signaling molecule that works as a messenger and activator for the immune system. “

The cytokine boosts the production of specific white blood cells, mainly monocytes and macrophages,” says Dr. Prashanth Kumar Kandalla, one of the leading authors of the study.

Although normally monocytes and macrophages were not known as the primary defense force against viruses, the authors found that they activated other immune cells, so-called natural killer cells, that help fight the virus.

“In case of immunocompromised patients, the number of white blood cells is very low. This is why their body is defenseless against infections. M-CSF treatment would boost the immune system by triggering the production of new white blood cells and restore the patient’s ability to fight the pathogen,” explains Dr. Kandalla.

The team could show that M-CSF boosted production of white blood cells in immunocompromised mice and in such a way protected them from an otherwise lethal CMV infection without affecting bone marrow transplantation.

Clinical trials needed

The study showed that the concept worked in mice and in human cells in a culture dish.

“We are keen to expand our findings and support them with data derived from patients in the clinic. For example, we would like to test our cytokine approach as a prophylactic intervention following bone marrow transplantation to prevent CMV reactivation. For this, clinical trials are necessary. We are now looking for partners who could help us finance such trials,” concludes Prof. Sieweke.

Because of its unique ability to boost the immune defence, the new approach is not limited to CMV or bone marrow transplantation patients. The authors expect that it could also be useful to treat other viral infections, and help other patients with a weakened immune system, for example after sepsis or chemotherapy.

No comments yet