A novel glycoengineering platform, created by the laboratory of Assistant Professor Chris Lok-To Sham from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), is poised to revolutionise future production of vaccines and therapeutics to fight infectious diseases.

Glycoengineering aims to manipulate sugars to produce useful carbohydrates. This innovative platform simplifies the customising and production of sugar carbohydrates known as glycans that plays a crucial role in various therapeutic applications.

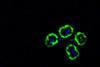

Sugar-adding enzymes called glycosyltransferases (GTs) produce glycans and control the structural diversity of glycans. The team found that the capsular polysaccharide (CPS), the sugar layer which encases many bacteria have extreme diversity, where its enzymes can be exploited to build many customised glycans.

Lego bricks

“These enzymes are like Lego. The more types of Lego bricks you have, the more unique types of glycans you can build,” explained Asst Prof Chris Sham from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at NUS Medicine.

Armed with this knowledge, Asst Prof Chris Sham and his graduate student Su Tong from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, together with their team from the Infectious Diseases Translational Research Programme at NUS Medicine, took advantage of the diverse pathways of the bacterial CPS and the ease of modifying its pathways to create this novel glycoengineering platform.

This platform provides increased versatility in modifying GTs, facilitating the engineering of newly-customised glycans. Customised glycans, essential for diverse therapeutic applications, requires a versatile platform capable of the insertion, deletion, substitution and general modification of glycan linkages.

Broadening the range

The team found that by relaxing the specificity of the precursor transporters, they could broaden the range of residues entering the cytoplasm. This innovation enables the production of customised glycans with unprecedented flexibility.

“The process of customising glycans, or glycoengineering, is made more challenging because it mostly relies on in-vitro approaches. These issues affect the efficient production of vaccines and other biological therapeutics. The new platform circumvents this challenge by demonstrating the possibility to genetically manipulate and engineer new glycans, giving rise to new knowledge about GTs, which ultimately signals an important advancement in glycoengineering,” Su Tong said.

To date, the team has already celebrated significant achievements, including the successful synthesis of clinically relevant glycans such as the Galili antigen, blood group antigens and Lewis antigens. These glycans can contribute to positive outcomes in the areas of organ transplants and blood transfusion when antibody rejection occurs in situations where the patient’s blood group is incompatible with the donor, resulting in severe inflammation and cell death.

Future steps

Asst Prof Chris Sham is optimistic about the future development of this glycoengineering platform in creating more glycans for a broad variety of specific needs.

“The current focus is to make glycans found in mammals, but in the future the team hopes to use this novel platform technology and adapt it to multiple bacterial species to generate more useful carbohydrates for other applications, such as countering immunological paralysis and graft rejection.”

The paper was published in Science Advances, titled ’Rewiring the pneumococcal capsule pathway for investigating glycosyltransferase specificity and genetic glycoengineering’.

No comments yet