A female White-eared opossum (Didelphis albiventris) found dead in 2021 in Bosque dos Jequitibás Park in the center of Campinas, one of the largest cities in São Paulo state, Brazil, died from rabies meningoencephalitis.

The report was published by a group of researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) and Adolfo Lutz Institute (IAL), the regional reference laboratory, working with health professionals affiliated with public institutions in São Paulo city and Campinas.

Reported in an article published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, the finding serves as an alert to the presence of the virus, which is deadly to humans, in the urban environment.

Monitoring mammals

“Dog rabies is no longer present in São Paulo state, thanks to the success of vaccination campaigns for domestic animals. For this reason, it’s important to monitor other mammals that can act as vectors for the virus, especially animals neglected by this kind of surveillance, such as opossums,” said Eduardo Ferreira Machado, first author of the article. He conducted the study for his PhD research at the School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science (FMVZ-USP) with a scholarship from FAPESP.

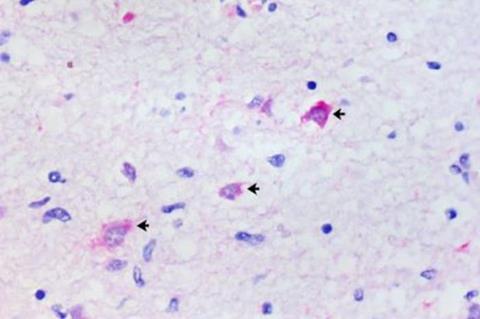

Neurological signs of the disease detected in the animal pointed to the form of rabies that causes paralysis and is transmitted by bats. Viral particles identified in other organs also showed that the infection was in the systemic propagation phase.

The opossum was one of 22 tested for rabies and other diseases by the group in 2021 as part of an epidemiological surveillance project conducted in partnership with the São Paulo City Department of Health and the Campinas Center for Zoonosis Control.

In the same year, the team analyzed 930 bats, 30 of which tested positive for rabies. More than half of these (17 or 56.7%) belonged to frugivorous species of the genus Artibeus. The rest (13 or 43.4%) were insectivorous and belonged to three different genera.

Bridge to humans

Transmission among bats and opossums may occur via their interaction, as these animals compete for habitats in nature, such as tree crowns, and in man-made environments, such as roof gables or backyards, for example.

In 2014, a case of cat rabies was notified in Campinas. The infection was traced to a viral variant found in bats. Both cats and opossums may prey on bats, and this was the most likely transmission path.

The researchers also drew attention to the fact that 15 of the 22 opossums analyzed had been killed by dogs. “Dogs can be a bridge between opossums and us, bringing rabies and other diseases to humans. It’s therefore important to monitor wild animals that live in cities,” Machado said.

Key to surveillance

According to José Luiz Catão-Dias, a co-author of the article and Machado’s thesis advisor at FMVZ-USP, opossums are key to this type of surveillance because they adapt well to urban environments without necessarily ceasing to interact with areas of forest.

“Even so, they’re neglected. Hardly anything is known about the diseases they may have and might transmit to us,” said Catão-Dias, who is principal investigator and grantee for the project “Comparative pathology and investigation of diseases in Neotropical marsupials, order Didelphimorphia: a surveillance proposal for a group of mammals neglected in wild fauna health studies”, supported by FAPESP.

The authors note in the article that a study conducted in the 1960s led to initial suggestions of resistance to the rabies virus among opossums, an assumption reinforced by the scarcity of reports of rabies in these animals.

Transmission occurs

The low prevalence of rabies among opossums in North America, where wild carnivorous mammals are natural reservoirs for viruses, has been explained as due to their low body temperature (34.4 °C-36.1 °C) and the minimal possibility of surviving an attack by a rabid animal. However, the Brazilian study shows that transmission occurs and should be monitored.

The researchers continue to analyze dead animals brought to IAL’s Pathology Center, for the purposes of monitoring the presence of both rabies and other diseases. They plan to partner with institutions in other countries, such as Australia, so as to be able to conduct surveillance of opossums and other marsupials.

“The Australians have a great deal of experience in this area. We can make comparisons that will be useful to both countries,” Catão-Dias said.

No comments yet