Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst-based New England Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases (NEWVEC) have published new findings on Powassan virus, an emerging tick-borne illness that can cause life-threatening encephalitis and meningitis. The study reports that people bitten by black-legged (or deer) ticks that tested positive for the virus did not show signs or symptoms of disease.

The research, led by Stephen Rich, NEWVEC executive director and professor of microbiology – “Passive surveillance of Powassan virus in human-biting ticks and health outcomes of associated bite victim” – was published DATE in a letter to the editor in the journal Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

READ MORE: New testing approach improves detection of rare but emerging Powassan virus spread by deer ticks

READ MORE: White-tailed deer blood kills bacteria that causes Lyme disease

“Our findings explain why there may be so few cases of Powassan virus, even as the number of Powassan-positive ticks appears to be increasing,” Rich says. “This situation may be similar to West Nile virus, another flavivirus, spread by mosquitoes.”

Nonspecific presentations

The paper suggests that “most Powassan-positive bites may cause nonspecific presentations that do not result in health care seeking or trigger testing for Powassan virus infection when health care is accessed.”

The NEWVEC research “represents the first instance of connecting passive surveillance of ticks with an indicator of clinical disease in humans,” the paper states. “Though a crude measure, interacting with bite victims gave a very simple picture that the clinical disease was not manifesting following exposure.”

The researchers also extrapolated for the first time the estimated number of people in the U.S. bitten each year by I. scapularis ticks, the commonly known deer ticks that spread the most prevalent tick-borne infection, Lyme disease, as well as other illnesses.

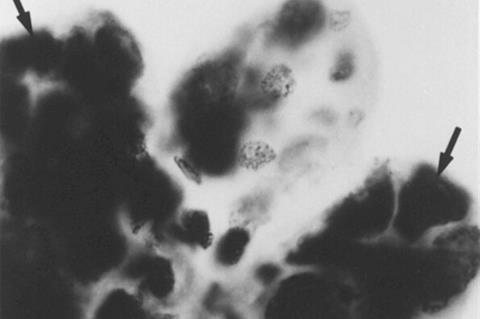

Blood-sucking tick

The blood-sucking I. scapularis – found in the eastern half of the U.S. and especially in the Northeast and upper Midwest – bite and feed off some 1.36 million people a year, whether they know it or not, the researchers estimate.

“Each case of Lyme started with a tick bite, although people often don’t recall being bitten by a tick,” says Rich, senior author. “Our simplified calculation of the total number of human tick bites emphasizes how many people are at potential risk of exposure to the myriad of different germs these ticks transmit.”

The estimate came amid an examination of data involving the application of Rich and team’s new and more accurate method of detecting the Powassan virus in ticks. The researchers looked to the TickReport, a tick pathogen testing service in Massachusetts, to describe the escalating presence of Powassan virus in the Northeast.

TickReport

At least 476,000 cases of Lyme disease occur annually, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates, which means at least 476,000 ticks feed on humans long enough to transmit the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria that causes Lyme. Borrelia prevalence in ticks is conservatively estimated at <35%, so those 476,000 human cases represent 35% of the estimated 1.36 million people bitten by at least one tick.

By this same reasoning, the researchers estimate that between 3,000-5,000 people each year are exposed to ticks that carry Powassan virus in the U.S.

In the decade ending in 2023, there has been a fourfold increase in the number of human Powassan virus cases reported to the CDC – from 64 to 270. Since 2004, the CDC has recorded 311 hospitalizations and 44 deaths due to Powassan virus.

Fourfold increase

“The serious concern posed by Powassan virus stems from the human-biting frequency of I. scapularis and the association of reported short attachment times (<180 minutes) with severe cases of the disease,” the paper states.

By comparison, transmission of the Borrelia bacteria that causes Lyme is believed to most often take at least 36 hours.

The research focused on 14,730 deer ticks tested by TickReport from 2015-2023, 13,450 of which were human-biting encounters. The Powassan virus was identified in 42 of those ticks, including 38 from humans. In follow-up communication with those bite victims, none reported symptoms of the virus, even though the tick attachment time averaged well above the presumed minimum time needed for transmission of the virus.

Impact of co-infections

The reported bite location of the 38 human cases were: 27 in Massachusetts, three in Connecticut, two each in New York and New Jersey, and one each in New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont and Wisconsin.

The ticks that tested positive for Powassan virus were found to have up to four other co-infecting pathogens: Borrelia burgdorferi (60%), Babesia microti (17%), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (5%) and Borrelia miyamotoi (2%).

“Future research must analyze the implications of these co-infections on diagnostics and the resulting clinical severity of the disease,” the paper states.

No comments yet