These colorful patterns are proof that bacteria and humans aren’t all that different — both harbor individuals that will take the easy way out when given the chance. And that lifestyle can quickly spread to the detriment of all.

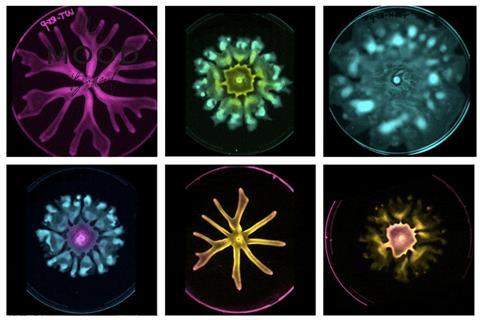

The bacterium shown here, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is an opportunistic pathogen that invades vulnerable areas like wounds and lungs if given a chance. While wild strains easily expand to fill an entire growth plate (like in early images above), Duke researchers discovered that they quickly lost their ability to grow into large colonies when cultured on growth plates over multiple generations (like in later images with stunted arms or no expansion).

It was a confusing result, as there wasn’t an obvious reason for the behavior, but the researchers eventually cracked the conundrum. The bacteria produce a slippery chemical to help them move out in search of nutrients — at least most of them do.

Increasing cheaters

When grown on relatively large flat surfaces, opportunities arose for some of the cells to simply let their neighbors do all the work. And when the same scenario was presented over and over again, these so-called “cheaters” became more and more common, until the colonies no longer produced enough slippery surfactant to spread effectively.

“When put into an environment where they have to cooperate to grow, the bacteria became more vulnerable to cheaters,” said Lingchong You, the James L. Meriam Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Duke. “It’s a phenomenon that happens in industrious human societies as well, but it’s a risk we all have to take to maximize our growth.”

The research was conducted by You’s former postdoctoral fellow Nan Luo, who is now an associate research professor at the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology in the Chinese Academy of Sciences, current PhD student Jia Lu, and current postdoctoral fellow Emrah Simsek.

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research (N00014-12-1-0631), the National Science Foundation (MCB-1937259) and the National Institutes of Health (R01GM098642).

No comments yet