A new UBC study shows that climate warming can potentially make bacterial and fungal infections deadlier for cold-blooded animals like corals, insects, and fish, raising questions about the broader risks warming temperatures pose to ecosystems and biodiversity—and potentially humans.

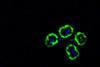

Drs. Kayla King and Jingdi (Judy) Li synthesized 60 experimental studies on cold-blooded animals with bacterial, fungal and other infections, noting that cold-blooded animals are directly dependent upon temperature and so, could be particularly sensitive to the effects of global warming.

The studies covered 50 species including land insects, fish, molluscs and corals—some of the most biodiverse and most at-risk ecosystems on the planet.

Using statistical models, the researchers found that cold-blooded animals with bacterial infections were more likely to die when exposed to higher temperatures compared to their usual environmental conditions.

Fungal sweet spots

The analysis showed that animals infected by fungal pathogens felt the impact of warming within a specific temperature range. They did not die more frequently as temperatures rose—unless the temperature rose towards fungi’s ideal range, known as the “thermal optimum.” At this point, infected animals were more likely to die. However, when temperatures became too high for the fungi to survive, death rates in infected animals decreased.

READ MORE: Satellite evidence bolsters case that climate change casued mass elephant die-off

READ MORE: Climate change likely to increase diarrhoeal disease hospitalizations by 2100s

“These findings suggest that climate warming may pose a greater risk to cold-blooded animals, an important part of the ecosystem,” said Dr. Li. She added that more research is needed on how rising temperatures impact warm-blooded animals, including humans.

Dr. King noted that the results offer insights to help forecast the risks to animal populations in a warming, disease-prone world.

No comments yet