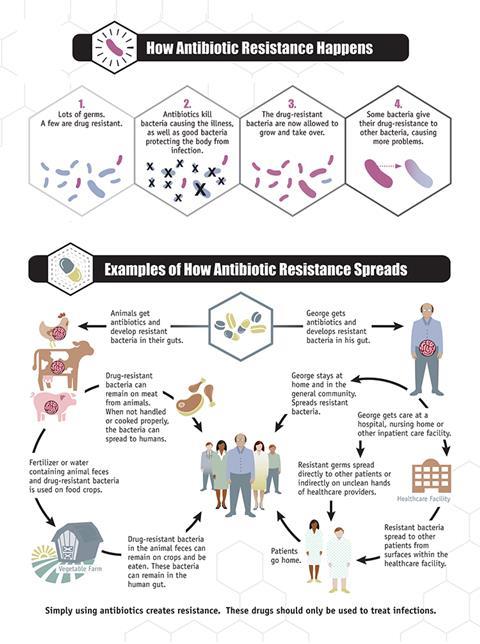

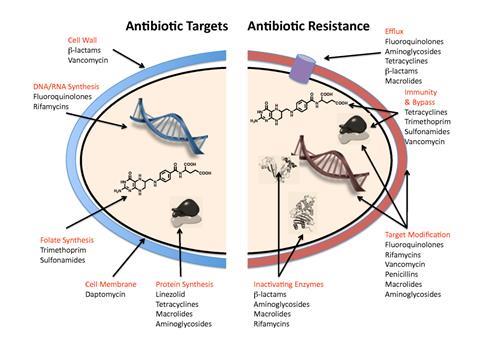

Antimicrobial resistance (the evolutionary ability of bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites to survive against the antimicrobials used to kill them) is a growing global health crisis, an ‘invisible pandemic’ that spreads through health systems, farms, the environment, communities and rivers the world over. But the complexity of the issue, the challenge of clearly communicating it, and the need for coordinated local, national and global efforts has left many actors unable to prioritise resources to fight it. As a result, efforts to mitigate AMR are dangerously siloed and ultimately dwarfed by the scale of the problem.

While the warning about AMR is as old as antibiotics themselves, global efforts to tackle antibiotic resistance are relatively recent. In 2014, the WHO released their first global report on antibiotic resistance, and it was a topic of discussion at the May 2015 World Health Assembly for the first time. This meeting initiated the development of the WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance, a tool for guiding countries to develop their own National Action Plans (NAPs) for mitigating AMR. Currently, 140 countries have NAPs in place. While this development demonstrates a clear positive shift, challenges remain for translating those plans into action – particularly in LMICs, where a lack of credible data and competing priorities make it hard for AMR to climb up the political agenda.

LMICs bear the greatest burden of AMR

A stark wake-up call on the issue occurred in early 2022 when The Lancet published the most comprehensive estimates of the burden of AMR to date. The study, led by the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) project, confirmed what many of us had feared for a long time. AMR is widespread and driven by complex and variable factors, especially inappropriate antimicrobial use in humans, agriculture and food-producing animals. And cruelly, it is LMICs that bear the greatest burden. According to the estimates, bacterial AMR directly attributed to the deaths of 1.27 million people around the world in 2019.

We know that contributory factors for a high AMR burden include both the prevalence of resistance in pathogenic bacteria and the incidence of critical infections in the population, such as lower respiratory infections, bloodstream infections and intra-abdominal infections. This infectious disease burden also tends to be higher in LMICs. Furthermore, health systems in low-resource settings already face considerable strain and struggle to create access to antibiotics for patients who require it. Therefore, context-specific solutions for tackling AMR must be developed and implemented to address these multiple challenges.

While antibiotic effectiveness is a global good, guaranteed access to the right antibiotic at the right time is inequitable and far from assured across the globe. Inappropriate antibiotic use threatens the efficacy of existing antibiotics, not only because of excess but also because of limited access. In many LMICs, counterfeit drugs, poor surveillance, limited diagnostics and lack of awareness, amongst other factors, mean that patients aren’t given the right drug to fight their infection, which tragically drives resistance further. Considering that no antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action have been added to the pipeline in the past 30 years, robust stewardship practices across the One Health spectrum are essential to retain and extend the efficacy of the current few drugs that still work, while making them available to the patients who truly need them.

ICARS in the global AMR landscape

Like the UK, Denmark has recognised the need to address the unequal global burden of AMR. For this reason, in Spring 2019, the Danish Government established the International Centre for Antimicrobial Resistance Solutions (ICARS). In November 2021, ICARS became an independent organisation, governed by an international board of directors, supported by a range of funding, implementing and mission partners.

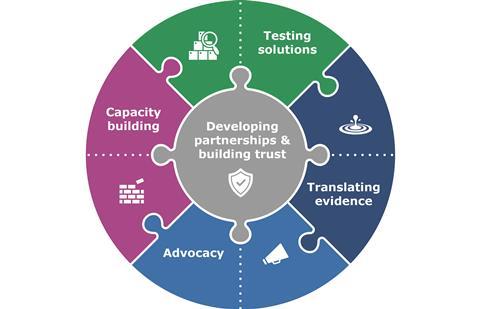

At ICARS, our mission is to partner with LMICs in their efforts to reduce drug-resistant infections, by co-developing and testing solutions to tackle AMR in the respective countries. ICARS uses implementation and intervention research methods to investigate the barriers and facilitators to uptake, adapts interventions to fit specific settings, and ensures the intentional consideration of how an intervention works within the wider social, political, economic and health context. Using the intervention-implementation research continuum as a framework, we work top-down and bottom-up, partnering with national ministries and local research institutions to co-develop context-specific, cost-effective and sustainable solutions that facilitate AMR mitigation on the ground, support implementation of NAPs, and have potential for scale-up. With a view to sustainability, ICARS’ projects build country capacity and contain both an economic and behavioural change component to ensure cost-effectiveness and long-term impact.

As AMR is a One Health challenge, our projects are implemented in the environmental sector (case study 1), across healthcare facilities or at the community level within the human health sector (case study 2), as well as in the agriculture, animal husbandry and food production sector (case study 3). Consequently, projects are led by the ministries of health, agriculture, animal husbandry and environment among many others, in collaboration with other key national stakeholders. By partnering with national ministries, we secure political commitment and ensure that efforts complement, and do not duplicate, support from other donors and partners working at the country level.

Given the data gaps and patchy awareness of AMR, ICARS recognises the need to make a clear economic case (both to the individual, and systems-focused) to guide decision-making for AMR interventions. Finally, since behaviour is a key factor that guides antibiotic use, ICARS projects integrate a variety of social science methods to gather specific data during an intervention that could support the uptake of results and eventual scale-up.

Since the beginning, ICARS has hit the ground running and now has a team of 27 scientific and operational experts from 15 countries, who support country teams to co-develop and implement projects. With 22 projects currently in implementation across Latin America, Asia, Europe and Africa, there are several examples of how our model works in practice – below we will explore three of them.

Case study 1: Reducing environmental contamination in Tanzania

In Tanzania, intensive poultry farming is on the rise to meet the increased demand for animal-derived protein and income. There is also an increased use of antimicrobials for the prevention and control of diseases on poultry farms. Evidence suggests that only a small portion of orally administered antimicrobials are utilised by the poultry, leaving the majority to be excreted in manure as parent or metabolised compounds. This poses a problem for the use of poultry manure, which is a desirable fertiliser in food production and aquaculture, as it could potentially lead to increased environmental contamination with antimicrobial residues and antimicrobial-resistant pathogens and genes throughout the food chain.

Since May 2022, a range of partners from the Tanzanian Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries, Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA), Zanzibar Livestock Research Institute (ZALIRI) and the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, Natural Resources and Livestock, Zanzibar have been exploring how the adoption of a simple and cost-effective poultry manure processing technology could lead to safer fertiliser and food products, while reducing the spread of antimicrobials in the environment. The learnings from this project are intended to inform and lead to revision of national policies with recommendations regarding the safe use of poultry manure in short-cycle horticultural crops in urban and peri-urban areas of Tanzania mainland and Zanzibar. The project is also expected to have the added benefit of creating employment opportunities for small businesses handling manure composting and fertiliser sales. Another important aspect is that since many of these businesses are women-led, it provides a unique window to increase understanding of the social and especially gender dimensions of AMR.

Case study 2: Introducing rapid-tests to strengthen antibiotic stewardship in Kyrgyzstan

Symptoms of respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are the most common cause of seeking healthcare, and the main reason for antibiotic overuse at the primary care level around the world. Up to 70% of RTIs are caused by viruses and therefore do not require antibiotic treatment.

In Kyrgyzstan, ICARS has launched a project that uses a point-of-care test to detect a marker for infection (C-reactive protein, CRP) as a guidance tool for stewarding appropriate use of antibiotics for sick children in primary healthcare centres. As a bedside test, CRP supports healthcare workers to quickly assess whether children with RTIs have a bacterial infection and therefore require antibiotics. Results from a pilot study have already shown that measurement of CRP effectively and safely reduced antibiotic misuse. Therefore, this intervention will now be rolled out on a larger scale across 14 healthcare centres in Kyrgyzstan. An economical evaluation of the intervention will also be performed to provide the evidence for cost effectiveness and efficacy of introducing this new tool, with the aim of making a clear case for national level scale-up of the intervention.

Case study 3: Improving access to diagnostics for pig farms in Colombia

In Colombia, pig farming has been one of the fastest growing agricultural and economic sectors in the last decade. This development has contributed positively to the country’s food security and socio-economic development in the regions where pigs are produced. However, as pig productivity increases there is an urgent need for strategic alignment with AMR mitigation efforts including surveillance, diagnostics, antimicrobial stewardship and robust biosecurity practices.

ICARS, together with the Global AMR Innovation Fund (GAMRIF), Porkcolombia, swine farmers and interdisciplinary experts on the ground, has conducted a pilot project regarding the access and uptake of diagnostics for better swine production in the country. The project aimed to assess the challenges and opportunities for increasing access and uptake of disease diagnostics at pig farms in the country. Emerging results show the need for improved training on laboratory services available to small- and medium-scale clinical protocols for treating the most prevalent infections and variable costs for accessing diagnostics given infrastructural barriers such as logistics and transportation. The full results will be launched over the coming months.

Staying nimble: Engaging with multiple stakeholders

Co-developing context-specific AMR solutions with multiple stakeholders is complex and time-consuming. While the process delivers long-term benefits via meaningful country-ownership, cross-sectoral engagement and political commitment, there are many challenges along the way. Firstly, the collaboration among multidisciplinary teams across, for example, social sciences, legal and policy issues, medicine, life sciences and engineering can be complicated when each discipline arrives from a different perspective with different frameworks, methodologies and approaches. Secondly, even after implementing a harmonious project with multiple stakeholders, defining the processes for synthesising qualitative and quantitative data, and translating them into improved policy and implementation programmes can take a long time. Moreover, even though implementation research methods generate context-specific solutions, there is a need to define similar contexts to avoid reinventing the wheel and instead facilitate transferability of findings by sharing learnings across similar geographies and contexts.

For lasting impact, AMR must be integrated into other key global development agendas, as well as national sustainable development strategies. Through creative collaboration and advocacy, we must draw the clear links between the AMR agenda and universal health coverage, climate change, health-system strengthening, gender equality, food security and clean water and sanitation. Furthermore, countries and stakeholders must be cognisant of the varied maturation of health systems, especially in LMICs, and the conflicting contributions that each sector makes to achieve its economic development objectives. To support sustainable AMR mitigation in LMICs, it is essential to strengthen the specific sectoral system activities of human health, animal health and environmental sectors, as well as measuring the value of such investments in reducing the AMR burden.

What’s next?

Over a short period, ICARS has generated more than 10 million USD for partnership projects, which includes vital in-kind contributions from LMIC partners. Since its establishment in 2019, ICARS has established itself as an independent non-profit organisation with a network of more than 70 partners across 16 countries.

However, the journey has just begun and much remains to be done. Important pieces of the puzzle to address inappropriate antibiotic use and AMR in LMICs are still missing. There is a clear need for a supportive ecosystem with harmonised goals and alignment of expectations among all partners in the local context to generate the crucial evidence needed to guide development and rollout of suitable, sustainable AMR mitigation solutions. Such evidence must include:

- Data on behavioural drivers of inappropriate antibiotic use, especially in the vulnerable populations (such as women, children, socially and economically deprived population groups) and a prioritisation matrix for AMR mitigation policy and programme rollout.

- Convincing economic arguments (business cases) for investing in AMR for LMICs where one-size-fits-all solutions cannot be used. Moving beyond modelling and simulation scenarios, there is need for individual, cohort-level and/or national-level data to guide implementation.

- Estimates for the cost of inaction on AMR. Breaking the status quo demands, by counting each missed opportunity.

- Innovative legal, regulatory and policy frameworks and solutions to promote appropriate antibiotic use and limit the spread of AMR in resource-limited settings.

ICARS aims to engage internationally to mainstream AMR within current global agendas, including pandemic preparedness and sustainable development goals and support the introduction of an AMR lens on investments made by the World Bank Group, International Monetary Fund and other multilateral and bilateral lending and development finance facilities. This is to make sure AMR mitigation in LMICs remains a priority and we address this global challenge with a holistic concerted approach.

ICARS envisions a world where drug-resistant infections no longer pose a threat to the health of humans and animals, the environment, global food security and economic prosperity. This vision will only be realised through partnership, by working with national, regional and international partners. We champion a participatory, cross-disciplinary research approach that strives for alignment and collaboration across public, private and philanthropic sectors.

At ICARS, our invitation to partner is always open – learn more by visiting our website.

No comments yet