Jake A Smallbone reveals how a industry collaboration as part of his PhD led to work on a real world oil spill to uncover the fascinating ways that bacterial communities respond to pollution and can be deployed as biomarkers and in bioremediation.

Since the start of my educational journey, I have aimed to pursue a scientific career focused on tackling real world problems.

This led me to my current PhD research in Environmental Microbiology at the University of Essex under Dr Boyd McKew and Professor Terry McGenity, which has focused on the bioremediation of hydrocarbons by microbial communities in response to oil spills - specifically, how these communities respond to oil pollution and how they can be used for bio-monitoring purposes and subsequent clean-up.

READ MORE: Biosurfactants may offer green solution for tackling oil spills

READ MORE: Scientists uncover mechanism used by archaea to break down crude oil

Importantly, my PhD included the opportunity to collaborate with an industry partner, Oil Spill Response LTD (OSRL) with Dr Rob Holland acting as an external supervisor, providing his industrial and stakeholder expertise. Working directly with the oil spill response industry has greatly benefited the direction of my research and created unique opportunities for fieldwork.

Burst pipeline

Collaborating with OSRL allowed me to better understand the type of research questions that would directly benefit the oil spill response industry. With specific outcomes in mind, I was able to focus my research during the initial stages of my PhD and tailor my experimental designs to increase the impact and relevancy of my work to the industry.

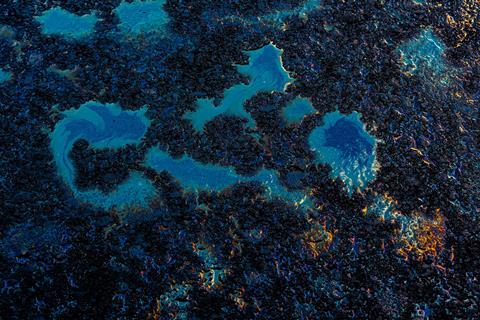

Halfway through my PhD, in March 2023, a spill occurred across a UK saltmarsh creek due to a burst pipeline. Due to our collaboration with OSRL, who were part of the initial response, my supervisory team were able to develop a NERC urgency grant with the aim of allowing me to sample the spill site and surrounding area to investigate how marine oil pollution impacts bacterial communities within marine sediment.

By the time of sample collection, monitoring of the spill site was fully underway. Discussions about our research with site owners and the company associated with the spill were facilitated by our industry collaboration. This proved successful and harboured a very positive working relationship between academic and industry personnel allowing us direct access to sample the spill site and various other locations throughout the creek. Overall, this collaborative effort was seamless and provided an enormous amount of useful background information required for the study. For example, OSRL were able to provide us with the clean-up and monitoring protocol which allowed us to design the initial survey for fieldwork sampling.

Bacterial response

Using DNA sequencing techniques, we investigate the ability of bacterial communities to adapt to a variety of environmental conditions during an oil spill and the various metabolic pathways that bacteria use to degrade oil hydrocarbons. These pathways can be exploited for the biodegradation of crude oil as a clean-up response strategy, in which bacteria will use the hydrocarbons within crude oil as a carbon source for growth.

Our work also identifies specific bacteria associated with these different degradation pathways. These potential bacterial ‘biomarkers’ could be used to indicate the health of the system due to their presence/absence within impacted regions.

Using these same techniques, we can also assess the impact of crude oil to important biogeochemical processes such as the nitrogen, sulphur and methane cycle, indicating any changes to system functionality. This was an extremely valuable experience to conduct microbial research in situ during an oil spill event that has provided us with a deep insight into the community composition, biogeochemical functionality of the system and their potential for hydrocarbon degradation.

Exchange of knowledge

Academia and industry can benefit from one another through the exchange of knowledge and data. In my case, I was able to use scientific expertise to provide industry collaborators with a detailed understanding of how microbial communities respond to pollutants such as crude oil which will help to inform remediation responses.

This work would not have been possible without support and insight from the industry, who provided the context for why the research is vital and facilitated access to the sampling site. Going forward, academia-industry collaborations will be crucial to the further development of biomonitoring techniques which aim to assess an environmental system’s capacity for biodegradation and its overall health, thus informing remediation strategies.

This for me personally, has highlighted the importance of academic-industry collaboration and has motivated me to keep building upon my industry network. I aim to continue developing my research questions in partnership with industries within environmental science to ensure the relevancy of my work for communities outside of academia.

Jake A Smallbone, University of Essex, School of Life Science, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester CO4 3SQ

Topics

- Bacteria

- Be inspired

- Bioremediation

- Boyd McKew

- Climate Action

- Early Career Research

- Healthy Land

- hydrocarbons

- Marine Biotechnology

- Marine Science

- Ocean Sustainability

- oil pollution

- Oil Spill Response LTD

- Rob Holland

- Sustainable Microbiology

- Terry McGenity

- UK & Rest of Europe

- University of Essex

- Waste Management

- Wastewater & Sanitation

No comments yet