‘Unhealthy’ gut microbiome patterns are linked to a heightened risk of death after a solid organ transplant, finds research published online in the journal Gut.

While these particular microbial patterns are associated with deaths from any cause, they are specifically associated with deaths from cancer and infection, regardless of the organ—kidney, liver, heart, or lung—transplanted, the findings show.

The make-up of the gut microbiome is associated with various diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and diabetes. But few studies have had the data to analyse the association between the gut microbiome and long term survival, explain the researchers.

And while a shift away from a normal pattern of microbes to an ‘unhealthy’ pattern, known as gut dysbiosis, has been linked to a heightened risk of death generally, it’s not clear whether this might also be associated with overall survival in specific diseases, they add.

Gut dysbiosis

To find out, they looked at the relationship between gut dysbiosis and death from all and specific causes in solid organ transplant recipients among whom the prevalence of gut dysbiosis is much higher than that of the general population. This makes them an ideal group to study the associations between gut dysbiosis and long term survival, say the researchers.

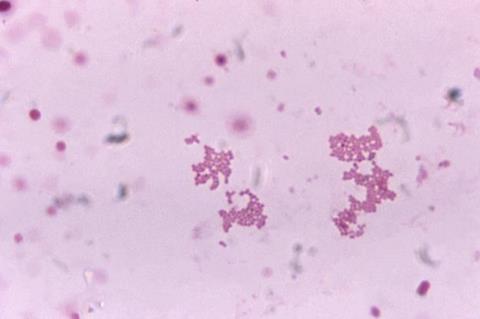

They analysed the microbiome profiles from 1337 faecal samples provided by 766 kidney, 334 liver, 170 lung, and 67 heart, transplant recipients and compared those with the gut microbiome profiles of 8208 people living in the same geographical area of northern Netherlands.

The average age of the transplant recipients was 57, and over half were men (784; 59%). On average, they had received their transplant 7.5 years previously.

Follow-up period

During a follow-up period of up to 6.5 years, 162 recipients died: 88 kidney; 33 liver; 35 lung; and 6 heart, recipients. Forty eight (28%) died from an infection, 38 (23%) from cardiovascular disease, 38 (23%) from cancer, and 40 (25%) from other causes.

The researchers looked at several indicators of gut dysbiosis in these samples: microbial diversity; how much their gut microbiomes differed from the average microbiome of the general population; the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes; and virulence factors which help bacteria to invade cells and evade immune defences.

The analysis revealed that the more the gut microbiome patterns of the transplant recipients diverged from those of the general population, the more likely they were to die sooner after their procedure, irrespective of the organ transplanted.

Similar associations emerged for the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors.

Bacterial species

The researchers identified 23 bacterial species among all the transplant recipients that were associated with either a heightened or lower risk of death from all causes.

For example, an abundance of four Clostridium species was associated with death from all causes and specifically infection, while an abundance of Hangatella Hathewayi and Veillonella parvula were associated with death from all causes and specifically infection.

And high numbers of Ruminococcus gnavus, but low numbers of Germigger formicilis, Firmicutes bacterium CAG 83, Eubacterium hallii and Faecalibacterium prausnitzi were associated with death from all causes and specifically cancer.

Second pattern

These last four species all produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that, among things, is an anti-inflammatory agent and helps maintain gut wall integrity.

The researchers further analysed all bacterial species simultaneously using AI. This revealed a second pattern of 19 different species that were also associated with an increased risk of death.

This is an observational study, and as such, no definitive conclusions can be drawn about the causal roles of particular bacteria.

But the researchers conclude: “Our results support emerging evidence showing that gut dysbiosis is associated with long-term survival, indicating that gut microbiome targeting therapies might improve patient outcomes, although causal links should be identified first.”

No comments yet