Studying epidemics can help us plan for the future and identify better ways of dealing with them. Now, in a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a multi-institutional research team led by the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, has worked out how to understand social-distancing behavior.

The research team obtained a solution for a complex optimization problem that describes how individuals adapt their behavior during an epidemic in order to balance the costs of infection and social distancing. A central assumption is that people are behaving rationally—they are seeking to obtain the best outcomes for themselves.

READ MORE: Mitigate or suppress—coming to grips with the COVID-19 pandemic

READ MORE: Powerful new AI can predict people’s attitudes to vaccines

Through their work, the team identified simple rules, previously unrecognized, that govern this decision-making. The team’s mathematical models demonstrated that the social distancing of rational individuals ought to be proportional to the number of cases and the infection cost.

Surprisingly simple

“What we found was surprisingly simple,” says Simon Schnyder, lead author of the study. “Although this behavior was previously thought to be quite complex, our results support the intuition that with greater infection cost and more cases, more rational social distancing will occur.”

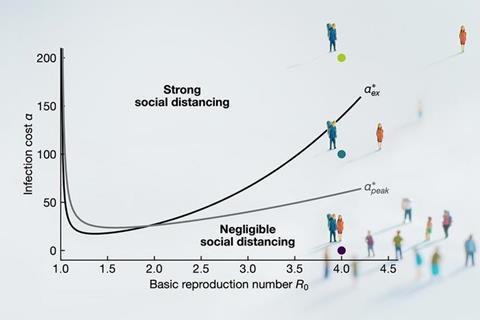

The team provides clear guidelines for predicting population behavior based on just two factors: the disease’s basic reproduction number and the estimated cost of infection. Using these, officials can forecast whether a population will engage in significant voluntary social distancing or continue normal activities. This would explain why during the COVID-19 epidemic we saw a reduction in socializing, even in societies in which no public lockdowns were enforced.

Mathematical explanation

“Our findings may seem straightforward, but being able to offer a simple mathematical explanation for this complex behavior represents a major advance in the field of behavioral epidemiology,” explains Matthew Turner, senior author of the study. This work also gives scientific validation to public health approaches that were developed intuitively during previous epidemics like HIV.

The results of this study will be useful for governments who need to design intervention strategies for future epidemics. Furthermore, the study offers a useful target for members of society to aim for when the next epidemic comes around: act rationally.

No comments yet