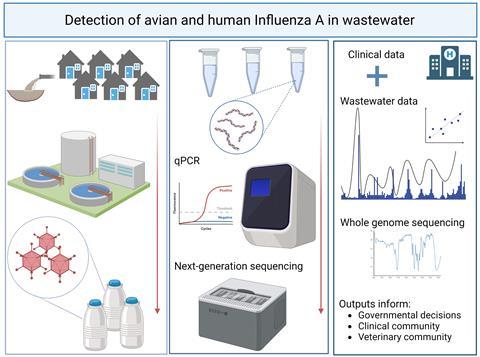

Researchers monitoring wastewater for avian and human influenza A virus have detected a surge in virus as the flu season got underway, showing that the technique could act as an early warning system for these and other pathogens.

Genetic material closely related to that found in the H5N1 strain of avian influenza showed up in the wastewater samples, taken from the sewage system in Northern Ireland.

The studies, which demonstrated the feasibility of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) as a tool for combined avian and human influenza A virus (IAV) genomic surveillance, were showcased by senior research fellow Dr Andrew Lee of Queen’s University Belfast at the recent Letters in Microbiology ECS Careers symposium at Riddel Hall in the city.

Pandemic potential

“This highlights the veracity of WBE as a One Health surveillance approach to provide rapid and reliable information on the incidence and spread of IAV, a pathogen known for its pandemic potential,” he said.

“Sequencing allows us to check for new variants which could arise and threaten the health of the population – either bird, animal or human. WBE is the first line of defence indicating that a disease is present before large numbers of individuals fall ill - it thus serves to augment both veterinary and clinical testing and help inform governmental decision making.

“Importantly, testing a whole community or population in one sample of wastewater is a much more cost-effective approach than testing large numbers of individuals.”

Mercurial pathogen

Dr Lee describes IAV, a significant endemic pathogen of humans and wildlife, as mercurial in nature, evolving rapidly and prone to emerging unpredictably from wild bird reservoirs to fuel outbreaks and pandemics via zoonosis.

“We aimed to confirm that targeted sequencing of avian IAVs from wastewater is possible. This would offer a resource efficient approach to community genome surveillance of wild bird populations and provide an opportunity for early detection of potential emerging avian IAV infection, in particular those displaying possible mammal compatibility, alongside their human counterparts,” he said.

“Screening and sequencing of IAV from environmental samples such as wastewater could conceivably provide a more comprehensive picture of circulating viral diversity and offer a rapid, reliable, and year-round source of information on the incidence and spread of this known pandemic causing pathogen.”

IAV variants

IAVs can be divided into numerous subtypes and variants with noted differences according to which host the strain is adapted/endemic to. WBE has been previously used to examine the levels of human IAV in populations but has not been investigated as a means to track the spread of avian IAV nor sequence it despite the acknowledgement that wastewater treatment works (WwTW) provide some of the most valuable artificial habitats for birds throughout the year in the UK and abroad.

“Our aim was to use a RT-qPCR assay targeting a conserved pan-IAV gene sequence to monitor the wastewater, before and during the start of a typical influenza season, for IAV signal, followed by sequencing of any IAV positive samples using a whole-genome amplification approach to hopefully subtype influenza positive samples and provide more sequence data than previous, human focussed, studies have,” Dr Lee said.

“Using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), a number of wastewater treatment works (WwTWs) across Northern Ireland were screened from August to December 2022.

Highly conserved region

“Our adopted pan-IAV assay targets a highly conserved region of the IAV matrix protein (genome segment number 7) allowing detection of any IAV regardless of original host (i.e. avian or mammal). A pan-IAV whole genome sequencing approach using Oxford Nanopore long read technology was employed to characterise positive samples on the basis of genomic sequence identity, with phylogenetic analysis carried out to further explore the origin and relatedness of generated sequences.

“A dynamic IAV signal was detected in the wastewater from September onwards, with “Meta” whole genome sequences generated from IAV positive samples from locations across Northern Ireland displaying identity to both human and avian strains.

“The relative proportion of human IAVs increased over the sample period as expected as the typical influenza season began. A clear diversity in subtypes and lineages was detected (H1N1, H3N2, and avian H13, H16). Avian segments 5 and 8 closely related to those found in recent H5N1 isolates capable of mammal-to-mammal transmission were identified.”

Surprising information

The nature of wastewater samples, and the information you can glean from them, continues to surprise, he said.

“Despite the unique challenges such complex sample matrices pose, such as the heterogenous mix of PCR inhibitors present and the often-fragmented state of the biological target of interest, molecular detection, and sequencing of pathogens - bacterial, fungal or viral - from wastewater has been proven across the globe,” he said.

“The fact that our work now shows that WBE methods could have a central place in ‘One Health’ approaches to control the spread of zoonoses is a significant development.

“It therefore begs the question, ‘What other common pathogens that are not part of routine clinical or agricultural surveillance programmes, or are detected infrequently from clinical/veterinary systems, could WBE programs help monitor?’”

Judging value

Dr Lee points out that producing epidemiological information has financial and opportunity costs and information value can be judged by the losses avoided and the gains made.

“In the context of routine pathogen monitoring, tracking emerging threats or simple pandemic preparedness, the intelligence produced by WBE may be valued because it can be available earlier than other signals, resulting in earlier interventions, or provide an intelligence signal as a proxy for prevalence in the absence of (or as a less costly alternative to) other sources of population clinical and veterinary testing,” he says.

“However, WBE should be considered in the context of complementing established epidemiological methods to avoid data attrition, not supplanting them, as individual-level epidemiological data can provide explicit information around risk factors, severity, outcomes, and direct medical/veterinary interventions that WBE cannot.”

Next steps

It is now necessary to focus on protocol optimisation and replication efforts, he says.

“Can other WBE groups use our methods to also detect avian IAV and better resolve human IAV in their own sewage networks? Can influenza whole genome sequencing provide better information on virus diversity and evolution, which is actionable by public health/clinical/veterinary collaborators?” he asks.

“What does the environmental pan-influenz-ome look like - can we use WBE to track and sequence influenza B, C and D as well? Finally, what other environmental sample types could we apply our research findings to, to fully realise the potential of applied molecular genomic surveillance of IAV?”

Dr. Andrew Lee and Dr. Connor Bamford led the study described here, which has been pre-printed on medRxiv. Funding was supplied by the Department of Health for Northern Ireland as part of the Northern Ireland Wastewater Surveillance Programme run by Prof. John W. McGrath and Dr. Deirdre Gilpin.

No comments yet