A study from Tel Aviv University has found that the deadly epidemic discovered last year, which has essentially wiped out Eilat’s most abundant and ecologically significant sea urchins, has spread across the Red Sea and into the Indian Ocean.

According to the researchers, what appeared at first to be a severe but local epidemic, has quickly spread through the region, and now threatens to become a global pandemic.

The researchers estimate that since it broke out in December 2022, the epidemic has annihilated most of the sea urchin populations (of the species affected by the disease) in the Red Sea, as well as an unknown number of sea urchins, estimated at hundreds of thousands, worldwide. Sea urchins are considered the ‘gardeners’ of coral reefs, feeding on the algae that compete with the corals for sunshine – and their disappearance can severely impact the delicate balance on coral reefs globally. The researchers note that since the discovery of the epidemic in Eilat’s coral reefs, the two species of sea urchins previously most dominant in the Gulf of Eilat have vanished completely.

Alarming results

The study was led by Dr. Omri Bronstein from the School of Zoology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History (SMNH), together with research students Lachan Roth, Gal Eviatar, Lisa Schmidt, and May Bonomo, as well as Dr. Tamar Feldstein-Farkash from the SMNH. Research partners throughout the region and Europe also took part in the study, which encompassed thousands of kilometers of coral reefs. The alarming results were published in the leading scientific journal Current Biology.

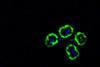

In addition, by using molecular-genetic tools, the research group at TAU was able to identify the pathogen responsible for the mass mortality of sea urchins of the species Diadema setosum in the Red Sea: a scuticociliate parasite most similar to Philaster apodigitiformis. The researchers explain that this unicellular organism was also responsible for the reoccurring mass mortality of Diadema antillarum in the Caribbeans about two years ago, following the notorious 1983 sea urchin population collapse there which led to the a catastrophic phase shift of the coral reef.

Mass mortality

As noted, in December 2022, Dr. Bronstein was the first researcher to identify mass mortality of sea urchins of the species Diadema setosum – the long-spined black sea urchins that were very common in the northern Gulf of Eilat, Jordan, and Sinai. Dr. Bronstein and his team also found that the epidemic was lethal for other, closely related sea urchins from the genus Echinothrix. These results suggest that the once most abundant and significant seabed herbivores in the region are now practically gone.

Thousands of sea urchins died a quick and violent death – within two days a healthy sea urchin turns into a bare skeleton with no tissues or spines, and most were devoured by predators as they were dying, unable to defend themselves. According to estimates, today only a few individuals of the affected sea urchin species remained throughout the coral reefs of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Reef gardeners

Dr. Bronstein explains that sea urchins in general, and specifically diadematoids (the sea urchin family affected by the disease), are considered key species essential for the healthy functioning of coral reefs. Acting as the reef’s ‘gardeners’, the sea urchins feed on the algae that compete with the corals for sunshine, and prevent them from taking over and suffocating the corals.

According to Dr. Bronstein, the most significant and widely studied mass mortality of sea urchins to date occurred in 1983, when a mysterious disease spread through the Caribbeans, killing most sea urchins of the species Diadema antillarum – relatives of Eilat’s sea urchins. Consequently, the algae spread uncontrollably, blocking the sunlight from the corals, and the entire reef was transformed from a coral reef into an algae field. Moreover, even though the mass mortality event in the Caribbeans occurred 40 years ago, both the corals and the sea urchin populations never fully recovered, with repeated mortality events observed through the years.

Scuticociliate parasite

The latest Caribbean outbreak in 2022 killed surviving populations and individuals from the former mortality events. This time, however, researchers had the scientific and technological tools to decipher the forensic evidence. A research group from Cornell University was able to identify the responsible pathogen, a scuticociliate parasite.

Dr. Bronstein emphasizes: “This is a growing ecological crisis, threatening the stability of coral reefs on an unprecedented scale. Apparently, the mass mortality we identified in Eilat back in 2023 has spread along the Red Sea and beyond - to Oman, and even as far as Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean.

“The deadly pathogen is carried by water and can affect vast areas in a very short time. Even sea urchins raised in seawater systems at the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, or at the Underwater Observatory, were infected and died, after the pathogen got in through the recirculating seawater system. As noted, death is quick and violent. For the first time, our research team was able to document all stages of the disease – from infection to the inevitable death – with a unique video system installed at the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat.

“Moreover, until recently, only one species of sea urchins was known to be impacted by this pathogen – the Caribbean species. Today we know that additional species are susceptible to the disease – all belonging to the same family of the most significant sea urchin herbivores on coral reefs.”

Routes of human transportation

Dr. Bronstein adds: “In our study we also demonstrated that the epidemic is spreading along routes of human transportation in the Red Sea. The best example is the wharf in Nueiba in Sinai, where the ferry from the Jordanian city of Aqaba docks.

”When we published our report last year, we already knew of sea urchin mortalities in Aqaba, but had not yet identified signs of it in Sinai. The first spot in which we ultimately did identify mortality in Sinai was next to this wharf in Nueiba. Two weeks later the epidemic had already reached Dahab, about 70km further south.

”The scene underwater is almost surreal: seeing a species that was so dominant in a certain environment simply erased in a matter of days. Thousands of skeletons rolling on the sea bottom, crumbling and vanishing in a very short time, so that even evidence for what has occurred is hard to find.”

Way forward

According to Dr. Bronstein, there is currently no way to help infected sea urchins or vaccinate them against the disease. We must, however, quickly establish broodstock populations of endangered species in cultivation systems disconnected from the sea – so that in the future we will be able to reintroduce them into the natural environment.

“Unfortunately, we cannot repair nature, but we can certainly change our own behavior. First of all, we must understand what caused this outbreak at this time. Is the pathogen transported unknowingly by seacraft? Or has it always been here, erupting now due to a change in environmental conditions? These are precisely the questions we are working on now.”

Topics

- Asia & Oceania

- coral reefs

- Diadema setosum

- Echinothrix

- Environmental Microbiology

- Gal Eviatar

- Indian Ocean

- Infectious Disease

- Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat,

- Lachan Roth

- Lisa Schmidt

- May Bonomo

- Middle East & Africa

- Ocean Sustainability

- Omri Bronstein

- Parasites

- Philaster apodigitiformis

- Red Sea

- Research News

- Reunion Island

- sea urchins

- Tamar Feldstein-Farkash

- Tel Aviv University

- Veterinary Medicine & Zoonoses

No comments yet