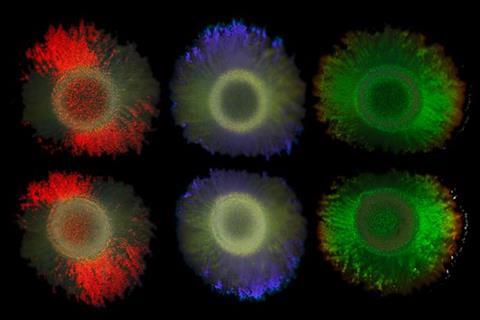

The iridescent colors known from peacock feathers or butterfly wings are created by tiny structures that reflect light in a special way. Some bacterial colonies form similar glittering structures.

In collaboration with the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Utrecht University, University of Cambridge, and the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, the scientists sequenced the DNA of 87 structurally colored bacteria and 30 colorless strains and identified genes that are responsible for these fascinating colonies.

READ MORE: Fermentation breakthrough delivers sustainable food coloring that’s better than beetroot

READ MORE: Microbial cell factories can produce eco-friendly food and cosmetic colourings

These findings could lead to the development of environmentally friendly dyes and materials, a key interest of the collaborating biotechnology company Hoekmine BV.

Predictions with artificial intelligence

The researchers trained an artificial intelligence model to predict which bacteria produce iridescent colors based on their DNA.

“With this model, we analyzed over 250,000 bacterial genomes and 14,000 environmental samples from international open science repositories,” says Prof. Bas E. Dutilh, Professor of Viral Ecology at the University of Jena and researcher in the Cluster of Excellence ‘Balance of the Microverse’. “We discovered that the genes responsible for structural color are mainly found in oceans, freshwater, and special habitats such as intertidal zones and deep-sea areas. In contrast, microbes in host-associated habitats such as the human microbiome displayed very limited structural color.”

Ecological significance and future applications

The study results indicate that the colorful bacterial colony structures are not only used to reflect light. Surprisingly, these genes are also found in bacteria that live in deep oceans without sunlight.

This could imply that the colors could reflect deeper processes of cell organization with important functions, such as protecting the bacteria from viruses, or efficiently colonizing floating food particles. These findings could inspire new, sustainable technologies based on these natural structures.

The international research project exemplifies how two profile lines of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, LIFE and LIGHT, can find each other. It also addresses the goals of the Cluster of Excellence “Balance of the Microverse”, where Prof. Dutilh has held one of four ‘Microverse Professorships’ as an Alexander von Humboldt Professor since 2021. The cluster investigates the complex relationships within microbial communities, and the role of colony structure in microbial interaction is one of the key research questions.

Topics

- Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning

- Bacteria

- Bas E. Dutilh

- Economic Equality

- Friedrich Schiller University Jena

- Healthy Land

- Hoekmine BV

- Industrial Microbiology

- Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures

- Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces

- Netherlands Institute for Sea Research

- Research News

- Sustainable Microbiology

- UK & Rest of Europe

- University of Cambridge

- University of Jena

- Utrecht University

No comments yet