New research out of Southern Cross University has found previously undocumented variation in coral heat tolerance on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, giving hope that corals’ own genetic resources may hold the key for us to help in its recovery and adaptation.

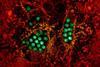

In a study published in Communications Earth and Environment, researchers measured the bleaching thresholds of more than 500 colonies of the table coral, Acropora hyacinthus, using a portable experimental system that was used at sea at 17 reefs spanning the Great Barrier Reef.

READ MORE: Microplastics found in all three parts of coral anatomy

READ MORE: Coral colony from Fiji reveals warmest temperatures in more than 600 years

The study was led by Southern Cross University PhD candidate Melissa Naugle, with a team from Southern Cross University, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), the University of Queensland, and the Research Institute for Development in New Caledonia as part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP).

Heat-tolerant corals

“We found heat-tolerant corals at almost all the reefs that we studied, highlighting how corals across the entire Great Barrier Reef may hold genetic resources that are important for protection and restoration,” said Melissa.

“This is important news for corals, which are experiencing the 4th global mass bleaching event and unprecedented summer sea temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef. Naturally occurring heat tolerance variation is crucial for corals to adapt to climate warming and for the success of restoration initiatives.”

These findings were substantiated in another recent study by co-author and fellow Southern Cross University PhD candidate Hugo Denis, who also found widespread variation in heat tolerance in a different coral species.

Future generations

The results of this work have important implications for coral reef futures.

“Differences between individual corals is the fuel for natural selection to produce future generations of more tolerant corals,” said Dr Line Bay, co-author and Senior Principal Research Scientist and Research Program Director at AIMS.

“Developing a solid understanding of this variation is crucial to understanding how corals will adapt to climate warming.”

Dr Cedric Robillot, Executive Director of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, said: “This work highlights the availability of naturally heat-tolerant corals that can be targeted by RRAP, as a large-scale reef restoration and conservation effort, to protect this critical ecosystem from warming ocean temperatures that are already locked in from climate change.”

Restoration programs

Dr Emily Howells, co-author and Senior Research Fellow at Southern Cross University and Project Lead in the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, said: “Heat tolerance variation can be useful for restoration programs such as selective breeding, which may accelerate adaptation to produce offspring better suited to warmer waters. Though, this outcome depends on how much of the heat tolerance variation we observe is tied to heritable gene variants.”

The most heat tolerant corals identified in this study are currently being used for a selective breeding trial through the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program.

The study reported not only the extent of the variation in coral heat tolerance, but also investigated the sources underlying that variation.

“In this paper we explored many of the environmental influences that shape heat tolerance, like thermal history, nutrient concentrations, and the symbiotic algae that live inside coral tissue,” said Melissa.

Genetic differences

While the study found that environmental factors like sea temperatures were important in influencing heat tolerance, there was substantial heat tolerance variation that could not be explained by the environment and is likely due to genetic differences among individual corals.

“Next, we’ll analyse DNA-sequencing data from these individuals to identify gene variants associated with heat tolerance. This can help us understand the adaptation potential of natural coral populations and inform selective breeding work,” Melissa said.

“While restoration initiatives like selective breeding may strengthen coral populations, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is most crucial to give coral reefs the best future possible.”

Topics

- Acropora hyacinthus

- Asia & Oceania

- Australian Institute of Marine Science

- Cedric Robillot

- Climate Action

- coral

- Early Career Research

- Emily Howells

- Great Barrier Reef

- heat tolerance

- Hugo Denis

- Line Bay

- Melissa Naugle

- Ocean Sustainability

- Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program

- Research Institute for Development

- Research News

- Southern Cross University

- University of Queensland

No comments yet