SECORE International’s Coral Seeding approach utilizes assisted reproduction, the breeding of corals, for reef restoration. This approach is realized within a training and partner network throughout the Caribbean.

Now, a peer-reviewed study shows that all the effort was worthwhile: during the devastating heatwave in the Caribbean in 2023, the young, bred corals out on the reef stayed healthy while most of the remaining wild corals bleached and many died in the aftermath.

READ MORE: We should help coral microbial symbionts evolve heat tolerance in the lab, researchers say

READ MORE: Scientists uncover the secret synchronised sex life of coral

The summer of 2023 was deadly for many corals in the Caribbean Basin. An unprecedented heatwave, in intensity as well as in duration, hit the Caribbean with catastrophic effects. Coral bleaching spread in the Caribbean Sea, and as high (seawater) temperatures persisted, many weakened corals died.

Glimmer of hope

Sandra Mendoza Quiroz, SECORE’S Restoration Coordinator in Mexico, was the first to discover a glimmer of hope during that desperate time. When Mendoza Quiroz and her colleagues set out for a routine monitoring dive to check on the health of their out-planted corals, expectations were low.

But then, amidst the bleached corals on the reef, she spotted the first young corals that they had grown, and they appeared to be completely healthy. A similar observation was made by SECORE’s team on Curaçao: bred corals of a different species were withstanding the elevated temperatures as well.

“We were excited to observe this pattern showing another benefit of using assisted coral recruits in restoration, “says Dr. Margaret Miller, SECORE’S Research Director. “Our scientists in Curaçao and Mexico, together with our partner Coralium Lab (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), gathered data on the health status of several species and cohorts of our outplanted corals. Then we contacted partners throughout our Caribbean Restoration Network to see how widespread and consistent this pattern was.

”Fundación Dominicana de Estudios Marinos, the Nature Conservancy in the Caribbean and Reef Renewal Foundation Bonaire contributed additional data. This provided confirmation that assisted recruits of six species of reef building corals at 15 individual reef sites in five nations throughout the Caribbean Basin showed the same pattern: young corals bred for restoration are a lot more resistant to bleaching under extreme levels of heat stress than the prevailing corals on the reef.”

Heat tolerance

The study Assisted sexual coral recruits show high thermal tolerance to the 2023 Caribbean mass bleaching event was just published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOSONE (Miller et al. 2024).

It is the first scientific evidence showing that restored corals from approaches using natural reproduction have improved resistance over natural and small fragmented corals under extreme seawater temperatures well above bleaching thresholds.

“I have been working on breeding corals in the Caribbean over the past thirty years, while simultaneously witnessing tremendous coral loss - due to disease, hurricanes and heat waves - and the unraveling of the communities that depend on them,” says Dr. Miller. “These results provide a lot of encouragement and confirmation that restoration using assisted coral recruits can play an important role in orchestrating coral persistence into our warmer future. Nonetheless, truly securing the future of coral reefs is absolutely dependent on humankind’s success in controlling global warming.”

Fragmentation approach

Just a decade ago, corals were propagated only by fragmentation, that is, breaking a fragment off a source colony to grow a new colony which is its clone. Small coral fragments are grown in nurseries and transplanted onto the reef manually. Today, Coral Seeding - breeding corals for restoration - is implemented throughout the Caribbean by SECORE‘s Training and Capacity Building Program.

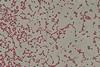

SECORE’s Coral Seeding approach involves collecting coral spawn from wild corals, fertilizing the eggs and sperm in the lab (or on a boat or beach), and thus producing millions of coral embryos. The developing coral larvae are grown in enclosures in the ocean and settled on special substrates. After the corals have reached a certain size, the substrates are outplanted onto the reef.

Every time a population reproduces, new offspring receive newly mixed sets of genes through recombination, making them different from their parent colonies and thus enabling adaptation. The aforementioned study shows that only the young corals produced via breeding exhibit a higher resistance to bleaching compared to adult coral colonies and fragments. Although naturally occurring offspring could perform similarly under elevated temperatures, general recruitment failure of reef-building species in the Caribbean means hardly any natural offspring occur.

Coral restoration

“I am excited about the very positive results of this large study since it shows that our Coral Seeding approach is an important contribution to help coral reefs dealing with climate change,” says Dr. Dirk Petersen, SECORE’s Founder and Executive Director. “Our investment over the past five years to build a large network for coral restoration in the Caribbean has paid off. This network not only produces and outplants tens of thousands of corals every year but could also immediately assess how these corals responded to this unprecedented heat wave. Our priority is now to further scale efforts to the ecosystem level. “

Successful coral restoration clearly needs a cooperative strategy; not only working among disciplines such as science and engineering, translating findings into low-tech approaches that prioritize feasibility and large-scale implementation, but also working together with partners in a multifaceted network. It’s also about logistics, effectiveness, and training, as well as applying tools and technology on-site – embedded in sound management strategies that integrate the local community.

It is obvious that if we neglect to take actions against accelerating climate change and the impacts it has on our planet, coral restoration alone won’t cure our reefs in the long run. However, restoration can buy us the urgently needed time to support coral populations to survive for the next century.

Successful model

“Our Caribbean Training and Capacity Building Program has turned out to be a successful model, which we urgently need to take to other regions across the world,” says Dr. Petersen. “Last year was the first time that we witnessed such extreme weather events, but it certainly won’t be the last; and such extreme events will not remain unique to the Caribbean.

”Restoration measures are best implemented at an early stage to strengthen the reefs. Once degradation has reached a critical level, restoration becomes much more challenging.

”To prepare practitioners in other regions for implementing sustainable restoration at their reefs, we have established some solid partnerships in the Indo-Pacific. This summer, we hosted our first initial training for participants from US jurisdictions in the Western Pacific. We will also establish a SECORE team in Mauritius by the end of this year. This new base will serve as a distribution point for restoration training in the Indian Ocean. Restoration truly is a cooperative effort - let’s all work together to give these valuable ecosystems a future!”

Supporting documents

Click link to download and view these fileslow-res (25)

Other, FileSizeText 0.13 mb

No comments yet