A peptide synthesized by researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil protected human lung cells against infection by SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory and eliminated the inflammation caused by the virus in mice susceptible to COVID-19. Development of the peptide was inspired by the protein ACE2, the human cell’s natural receptor for SARS-CoV-2.

An article describing the research is published in the journal Antiviral Research. As noted by the authors, the results point to a possible route to the creation of antiviral blocker drugs that are more effective against the disease, which has killed more than 700,000 Brazilians to date.

READ MORE: Long-acting biologic has transmucosal transport properties that arrest Covid variants

READ MORE: Pathway into cell influences the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection

SARS-CoV-2 invades host cells by binding to the ACE receptor on their surface via its spike protein (S).

“The infection process is like a key fitting into a lock,” said Geraldo Aleixo Passos, last author of the article and a professor in the Department of Basic and Oral Biology at the Ribeirão Preto Dental School (FORP-USP). “The ‘key’ is the viral spike protein and the ‘lock’ is the cell’s ACE2 receptor. The ‘teeth’ on the key are the spike amino acid residues, which match the pattern of ACE2 amino acids, the ‘pins’ inside the ‘lock’.”

Opening the door

The spike amino acids and ACE2 amino acids interact, and this “opens the door” to the viral RNA, which then enters and infects the cell. The more efficiently they interact, the more virulent the infection will be. This explains why variant B.1.1.7 of SARS-CoV-2 was so much more contagious, as the same group of researchers showed in an article posted to the preprint platform bioRxiv in 2021 (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/35021).

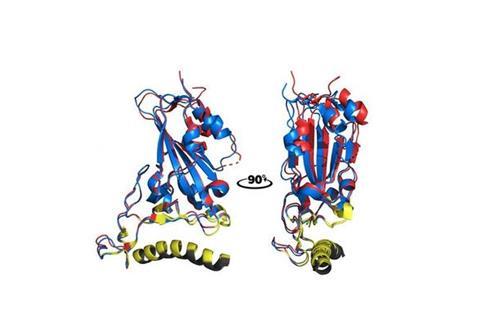

In the recent study, which was funded by FAPESP (projects 17/10780-4 and 19/02418-9), the scientists analyzed ways of blocking the spike-ACE2 interaction so as to protect human cells from infection. To this end, they synthesized a peptide that mimics the ACE2 receptor using protein bioinformatics programs and tested modifications to its amino acid residues to see if the changes did indeed prevent viral invasion.

During this process, they found certain parts of the ACE2 receptor to be crucial to the interaction – specifically, amino acid residues F28, K31, F32, F40 and Y41 present in alpha helix α1, one of this protein’s secondary structures.

Pulmonary inflammation

In vitro experiments using human lung cells and in vivo trials involving mice susceptible to the virus confirmed that the synthetic peptide not only controlled infection but also treated infected mice by drastically reducing the pulmonary inflammation caused by COVID-19.

“We succeeded in ‘tricking’ the virus by giving it part of the free ACE2 receptor [the synthetic peptide], which interacted with the spike before it could bind with the cell surface and thereby prevented its entry into the cell. In sum, we studied the structural basis for recognition of the ACE2 receptor by SARS-CoV-2 to develop a molecular barrier against the virus,” Passos said.

“COVID-19 was controlled with mass vaccination, which drastically reduced the number of cases and deaths, and was the best option to stop the disease from spreading. However, SARS-CoV-2 is still circulating, thousands of people are infected worldwide, and the virus will continue to mutate. Studies of its evolution suggest there could well be more outbreaks and even another pandemic like the one caused by the original strain from Wuhan and subsequent lineages. Precisely for this reason, we scientists must continue to investigate the matter,” Passos said.

Treatment for the immunosuppressed

A product that does not depend on the immune system to achieve its goal, like the peptide developed in this study, could be customized for every novel variant, he added. It works fast because it acts as a molecular shield, and can be effective as a near-instant blocker of the virus in immunosuppressed patients and immunocompromised children with a low immune response to vaccines.

The multidisciplinary, multicenter study was conducted by Brazilian scientists affiliated with the Center for Research in Virology, the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID), the Department of Genetics at the Ribeirão Preto Medical School (FMRP-USP), and the Renato Archer Center for Information Technology (CTI), an arm of the Ministry for Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI). Additional funding was supplied by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and the Ministry of Education’s Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

No comments yet