Analysis of occurrence and co-occurrence patterns shows the highest-risk clusters of chikungunya and zika in Brazil spreading from the Northeast to the Center-West and coastal areas of São Paulo state and Rio de Janeiro state in the Southeast between 2018 and 2021, and increasing again in the Northeast between 2019 and 2021.

In Brazil overall, spatial variations in the temporal trends for chikungunya and zika decreased 13% and 40% respectively, but 85% and 57% of the clusters in question displayed a rise in numbers of cases.

These findings are from an article published in Scientific Reports by researchers at the University of São Paulo’s School of Public Health (FSP-USP) and São Paulo state’s Center for Epidemiological Surveillance (CVE) who analyzed spatial-temporal patterns of occurrence and co-occurrence of the two arboviral diseases in all Brazilian municipalities as well as the environmental and socio-economic factors associated with them.

Worldwide rise

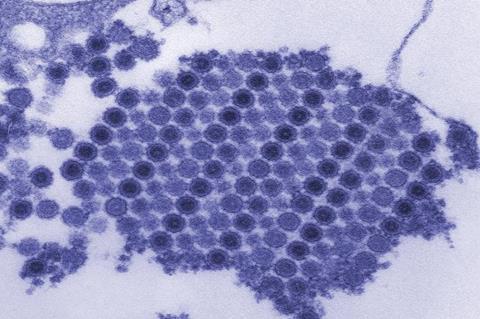

Considered neglected tropical diseases by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), chikungunya and zika are arboviral diseases caused by viruses of the families Togaviridae and Flaviviridae respectively, and transmitted by mosquitoes of the genus Aedes.

Case numbers of both diseases have risen worldwide in the last decade and expanded geographically: chikungunya has been reported in 116 countries and zika in 92, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the main health surveillance agency in the United States. Some 8 million people are estimated to have been infected worldwide, although the number may have reached 100 million in light of generalized underreporting of neglected tropical diseases.

Environmental factors

The emergence and re-emergence of chikungunya and zika are facilitated by environmental factors such as urbanization, deforestation and climate change, including droughts and floods.

“Identifying high-risk areas for the spread of these arboviruses is important both to control the vectors and to target public health measures correctly,” said Raquel Gardini Sanches Palasio, corresponding author of the article. She is affiliated with FSP-USP’s Department of Epidemiology, where she is a researcher in the Laboratory for Spatial Analysis in Health (LAES).

Working with her PhD thesis advisor, Francisco Chiaravalloti Neto, and other researchers at USP and CVE, Palasio analyzed more than 770,000 cases (608,388 of chikungunya and 162,992 of zika) diagnosed by laboratory test or clinical and epidemiological analysis; most were autochthonous (due to locally acquired infection). The analysis encompassed spatial, temporal and seasonal data, as well as temperature, rainfall and socio-economic factors.

Higher temperatures

The results showed that high-risk areas had higher temperatures and identified co-occurrence clusters in certain regions.

“In the first few years of the period the high-risk clusters were in the Northeast. They then spread to the Center-West – zika in 2016 and chikungunya in 2018 – and to coastal areas in the Southeast – in 2018 and 2021 respectively – followed by resurgence in the Northeast,” Palasio said.

“Spatial variations in the temporal trends for chikungunya and zika decreased 13% and 40% respectively, but numbers of cases rose in 85% and 57% of the clusters concerned. Spatial variation clusters with a growing internal trend predominated in practically all states, with annual growth of 0.85%-96.56% for chikungunya and 2.77%-53.03% for zika.

Summer and fall

“We also found that both diseases have occurred more frequently in summer and fall in Brazil since 2015. Chikungunya is associated with low rainfall, urbanization and social inequality, while zika correlates closely with high rainfall and lack of basic sanitation.”

Both are also more frequent in urban areas with less vegetation, she said, adding that socio-economic factors appear to correlate less with zika than with chikungunya.

“Both diseases have the same vectors and are similar in some other ways, so theoretically they should occur in the same places. We didn’t observe perfect overlapping in space and time, however,” Palasio said.

Next steps

A hypothesis raised by the researchers who conducted the study, which was funded by FAPESP, relates to socio-economic factors, environment and climate. The main source of data was the 2010 census, and next steps will include an update using fresh data from IBGE’s 2022 census.

“We also want to perform a spatial and temporal analysis using a broader dataset that takes socio-economic factors and climate (especially temperature and rainfall) into account together rather than separately,” Palasio said.

Another focus will be co-occurrence or overlapping of the two diseases. Future climate change models will be run under best-case and worst-case scenarios for greenhouse gas emissions.

No comments yet