Penicillin was hailed as “the silver bullet” when it was discovered, as it had the unprecedented quality of being able to kill disease-causing bacteria without harming the human body. Since then, a multitude of other antibiotics have been developed that specifically target a wide range of bacteria; but the more often they are used, the greater the risk that antibiotic-resistant strains will arise.

READ MORE: Scientists discover superbug’s rapid path to antibiotic resistance

READ MORE: Peptide cocktails could be key to fighting antibiotic resistance

In a study recently published in Frontiers in Microbiology, researchers from Osaka University have revealed that bacteria exhibit characteristic shape differences when they are resistant to drug treatment.

Antibiotic resistance is a major problem

Antibiotic resistance is a major public health problem worldwide, as it means that we have fewer and fewer options for treating bacterial infections. Identifying antibiotic-resistant bacteria quickly is important for ensuring that patients receive effective treatment; but the most readily available method for doing this involves several days of growing the bacteria in a lab and treating them with drugs to see how they respond.

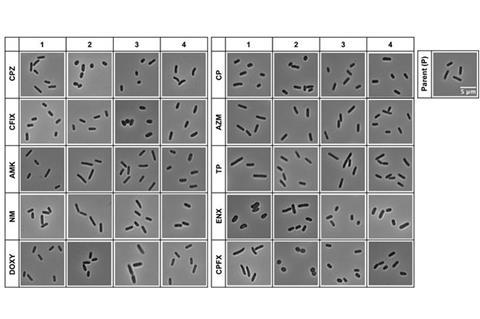

“There is some evidence that antibiotic resistance reveals itself in other ways; for example, the morphology of Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria changes when they are exposed to antibiotics,” says lead author of the study Miki Ikebe. “We were interested in determining whether this feature could be used to detect antibiotic resistance without actually treating the bacteria with antibiotics.”

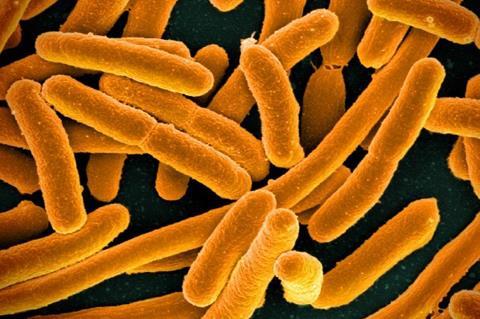

To do this, the researchers exposed Escherichia coli to fixed concentrations of different antibiotics, prompting them to develop antibiotic resistance. They then removed the antibiotic treatment and used machine learning to assess the shapes, sizes, and other physical features of the bacteria based on microscope images.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are fatter or shorter

“The results were very clear,” explains Kunihiko Nishino, senior author. “The antibiotic-resistant strains were fatter or shorter than their parental strains, especially those that were resistant to quinolone and β-lactams.”

Next, the researchers explored the genetic makeup of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria to see whether there was any connection between bacterial shape and antibiotic resistance. The results showed that genes related to energy metabolism and antibiotic resistance were indeed associated with the shape changes that were observed in the antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“Our findings show that drug-resistant bacteria can be identified from microscope images, in the absence of antibiotics, using machine learning,” says Ikebe.

Given that the bacteria that were resistant to quinolone, β-lactams, and chloramphenicol all exhibited similar shapes and sizes, it seems likely that the same genetic mechanism is responsible for antibiotic resistance in all of these strains. In the future, a machine learning tool could be used to rapidly assess samples taken from patients to help prescribe the right drug to treat their infection.

No comments yet