New research from King’s College London has revealed a connection between ancient viral DNA embedded in the human genome and the genetic risk for two major diseases that affect the central nervous system.

The study, conducted by researchers from King’s College London and Northwell Health, focused on human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs)—remnants of ancient retroviral infections that are now fixed features within our DNA.

READ MORE: Epstein-Barr Virus and brain cross-reactivity: possible mechanism for multiple sclerosis unveiled

READ MORE: Remnants of ancient virus may fuel ALS in people

Using a cutting-edge genomic technique, the team identified specific HERV expression signatures linked to multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as motor neurone disease). These findings suggest that viral elements within our DNA may play a role in the development of these neurodegenerative diseases.

Neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are characterised by progressive degeneration and loss of neurons, resulting in the deterioration of the nervous system’s structure and function. Multiple sclerosis is amongst the most common neurodegenerative diseases affecting young adults, with over 150,000 people in the UK living with this lifelong condition. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is less common, with approximately 5,000 cases in the UK, and it is associated with a more severe prognosis.

Published in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, the study marks an important advance in understanding the complex genetic architecture of neurodegenerative diseases. While previous studies hinted at a connection between HERVs and these conditions, this is amongst the first to pinpoint specific HERVs that are associated with disease susceptibility.

“Our findings offer robust evidence that specific viral sequences within our genome contribute to the risk of neurodegenerative diseases,” said Dr. Rodrigo R. R. Duarte, co-lead author of the study and Research Fellow at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology (IoPPN), King’s College London. “These sequences are not just static fossils derived from ancient viral infections—they must be actively influencing brain function in ways we are only beginning to understand.”

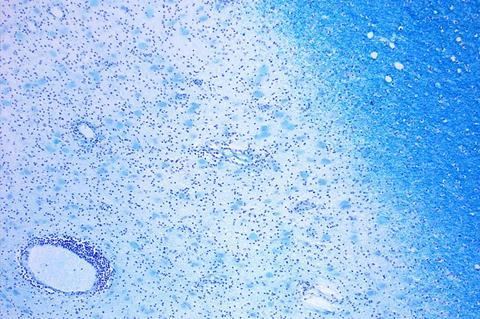

Brain samples

The researchers analyzed data from hundreds of brain samples to map out the relationship between HERV expression and genetic risk factors for four neurodegenerative diseases: Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple sclerosis.

They identified a robust HERV signature on chromosome 12q14 (MER61_12q14.2) associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and another on chromosome 1p36 (ERVLE_1p36.32a), associated with multiple sclerosis. These viral sequences appear to be involved in homophilic cell adhesion—a process essential for communication between cells in the brain.

No robust signatures were observed for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, although the authors highlight that larger studies may uncover novel associations in the future.

Promising direction

As the global burden of neurodegenerative diseases continues to grow—with over 50 million people currently affected worldwide, a number projected to nearly triple by 2050—these insights offer a promising direction for future research and treatment development. This discovery opens up new possibilities for therapeutic interventions targeting HERVs. By better understanding how these viral elements drive disease, researchers hope this could aid the development of novel treatments that could mitigate the impact of neurodegenerative diseases.

“Using large genetic datasets and a new analysis pipeline, this study is well equipped at pinpointing which specific HERVs are important in increasing susceptibility for neurodegenerative diseases”, said Dr. Timothy R. Powell, co-lead author and Senior Lecturer in Translational Genetics & Neuroscience at King’s IoPPN. “We now need to better understand how these HERVS impact on brain function, and whether or not targeting HERVs could offer new therapeutic opportunities.”

The research was part-funded by the National Institute for Health and Care (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and The Psychiatry Research Trust.

No comments yet