In Neurodiversity Celebration Week, fourth year PhD student Joshua Yates reveals the challenges of pursuing a career in microbiology with autism and dyslexia - and his advice to others.

Fresh from a long-needed summer holiday, brimming with excitement for the potential future of going to university in the coming year, with a view to a further career in microbiology, I opened my first set of A levels results - only to have my dream instantly crushed.

The beginning of my interest in STEM came via my special interests in space. I distinctly remember receiving a telescope and getting to see the details of the clouds on Jupiter and the intricate craters of the moon, which fascinated me. Fast forward to school and my interests were now at the other end of the scale - I enjoyed chemistry, namely organic and biochemistry, especially when this overlapped with biology at a microscopic level. Seeing animal and plant cells for the first time had me hooked.

With a vague idea of something cell or chemistry based as a future career interest, I was really lucky to complete my GCSE work experience at the Health Protection Agency (now UKHSA) at Porton Down. I was able to shadow several microbiologists and biochemists gaining insights into their research, even getting to see an electron microscope in action. It’s safe to say I came away from the experience inspired - I truly felt like this was the career I wanted to pursue.

Diagnosis and education

It was clear from a young age that I was different from my peers, I had little interest in playing with and making friends, almost always absorbed into various special interests, while becoming acutely overwhelmed by things other children my age wouldn’t.

By the age of 8 my parents finally had an explanation - I was autistic, although it wasn’t until the age of 19 I also found out I was dyslexic. But even with these diagnoses, my journey through education wasn’t ever plain sailing.

I struggled through school, whether as a result of my peers, a lack of understanding from teachers or inherent challenges as a result of my ASD. But college was where I really found my ASD began to impact me as I struggled with exam results not truly reflecting my ability.

Exam questions

This came to a head in my first year where I found the ambiguous nature of my AS biology exam questions (not being very autism friendly) resulted in grades far lower than I’d expected, at the time shattering any prospects I had of my dream Microbiology course.

If it weren’t for my brilliant head of sixth form at the time who suggested taking an extra year at college to restart biology I may well have given up on STEM completely. However, this meant I’d have to complete three years of A levels rather than two, leaving me with this feeling of always being behind.

Through support from my university’s disability team and the disability student allowance (DSA), I had a successful time during my UG and despite my MRes being severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, I was grateful to be accepted onto a DTP PhD.

Far from the comfort zone

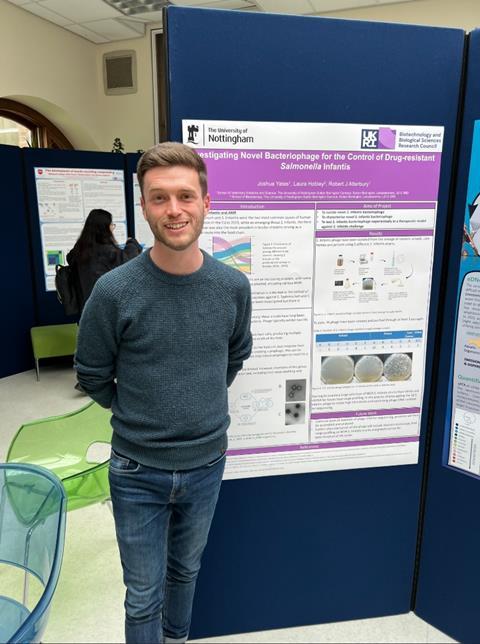

My PhD focused on isolating and characterising novel bacteriophage for use against Salmonella Infantis (notable for the emergent pESI-megaplasmid strains), utilising the wax moth larvae Galleria mellonella as an infection model.

But I found the PhD was a completely different challenge and far further from my comfort zone. Although you receive guidance from PIs, it’s a much more self-guided process which can be very challenging for neurodivergent students, who require structure. No two days during a PhD are ever the same - this is both what makes academia so exciting but also so scary. I struggled throughout my PhD with a lack of routine and much uncertainty.

The executive dysfunction aspect of ASD plagued my PhD experience, especially in the first couple years. Planning and organisation (both key skills that are developed during the PhD) were great challenges which at times impeded my speed of progress.

Autistic inertia was also another barrier to progress during my experience - starting new tasks, whether it was a set of experiments, data analysis or thesis type writing, could be difficult.

Autistic burnout

Another battle I faced during the PhD was autistic burnout, something I experienced at the end of my second year when things became really tough. This had a detrimental impact on my mental health and my executive functioning, both during the PhD and at home.

In addition to the pressures of the PhD, I’m aware that the masking I do on a day-to-day basis as a coping mechanism for the overwhelming world around me was also complicit in the burnout I experienced at this time. I ended up taking a three-month interruption at this stage of the PhD which I will forever be grateful for. I was able to finally take some time to recover from this burnout I’d been facing for several years up to that point, but again this meant I would be finishing my PhD later than my peers.

Guidance for PhD students

One of the most important pieces of advice I could give to autistic PhD students is on day 1, make sure you organise a meeting with the disability/welfare team at your institution to create a support plan for your needs.

Many may be able to adapt pre-existing support plans from previous study, but this document will be a crucial way in which you can communicate ways in which you may find tasks/environments challenging and strategies with which to cope with these instances, while also enabling people to gain a level of understanding which will help to them to support you with your studies as best as possible.

An approach I took during my PhD was to break the support plan down into PhD scenarios and the support needs I have that will be applied to these, e.g. supervision and supervisor meetings, laboratory time, presentations, viva examinations, extensions to thesis writing time.

Support from colleagues

Whether you have applied for a specific PhD project or a doctoral training programme (DTP) type PhD, despite the project itself being an important factor to consider (as you’ve got to be interested enough to get through those long and hard hours over the course of a minimum 4 years), in my experience your relationship with your PIs is the most important factor when considering the initial application stages, as they can essentially make or break your experience.

A supportive supervisor who is attentive at not only following your support plan, but ensuring those in the support group are also informed, will enable you to thrive during the entire experience, especially in times of hardship.

Further to this, the DTP type PhD programmes can be great for autistic students to both trial a project but also multiple supervisors during the rotation stage to gain a better understanding of which might be most compatible with you.

Some other tips I would recommend:

- Try and create a routine for yourself - maybe have one day as an experiment planning day, data analysis, writing schedule etc

- Do prioritise your mental health. It can be very easy to slip into autistic burnout which can be incredibly crippling with regards to both mental health and your overall productivity. This can be anything from scheduling in a rest day in the week, chats with a welfare team member of your institution, exercise (I’ve found running to be particularly refreshing), or taking time to absorb yourself into special interests to recharge.

- Don’t put too much pressure on yourself. It can be easy to put lots of pressure on yourself for deadlines/lab work/data analysis/writing when it may take you a little longer to complete certain tasks compared to your peers.

Guidance for PIs

Some tips and guidance I would give to PIs / supervisors of autistic students would be:

- Early on, have a meeting to discuss the best communication styles of the student (e.g. visual, verbal, written)

- Mediate with the disability / welfare support team of your institution to support your students

- I can’t recommend enough attending as much training as possible on neurodivergence to better understand and support ND students

- Further to the previous point, be mindful of the signs of autistic burnout in students, and try to make any advice or instruction explicit and clear instead of relying on inference of meaning, as this can be challenging for autistic individuals

- Consider the sensory aspects of the PhD your student might face in your institution’s work environment.

- For note taking in PI meetings, maybe suggest someone else taking notes to enable the student to fully focus on any instructions or advice for maximum clarity

- Supervisors could support students creating structure by setting short-term, interim or long-term research plans to negate executive dysfunction and autistic inertia

- Consider allowing a student to have a more flexible PhD experience with regards to attendance, working location and timelines of results, whether it be lab, analysis or writing.

A PhD is for you

If you have a passion for STEM and wish to pursue that further to a PhD you shouldn’t ever think you’re not worthy or that a PhD isn’t for you as an autistic individual.

Despite the challenges faced by autistic individuals - including myself - during the PhD experience (burnout, executive dysfunction, inertia), given the right environment and at your own pace, autistic students can thrive during a PhD.

Skills inherent to autism, including hyperfocus, attention to detail, a unique and creative way of thinking, are invaluable in academia. You will be successful as a PhD student not in spite of your autism - but because of it.

Joshua is a fourth year BBSRC DTP PhD Student in the School of Biosciences, University of Nottingham.

No comments yet