A team led by scientists at Scripps Research and the University of Amsterdam has achieved an important goal in virology: mapping, at high resolution, critical proteins that stud the surface of the Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and enable it to enter host cells.

The discovery, reported in Science on October 21 2022, details key sites of vulnerability on the virus—sites that can now be targeted effectively with vaccines.

“This long sought-after structural information on HCV puts a wealth of previous observations into a structural context and paves the way for rational vaccine design against this incredibly difficult target,” said study co-senior author Andrew Ward, PhD, professor in the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology at Scripps Research.

The study was the product of a multi-year collaboration that included the Ward laboratory, the lab of Gabriel Lander, PhD (also a professor in the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology at Scripps Research); the lab of Rogier Sanders, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam; and the lab of Max Crispin, DPhil, at the University of Southampton.

It is projected that roughly 60 million people globally—including about two million Americans—have chronic HCV infections. The virus infects liver cells, typically establishing a “silent” infection for decades until liver damage becomes severe enough to cause symptoms. It is a leading cause of chronic liver disease, liver transplants and primary liver cancers.

The origins of the virus are uncertain, but it is thought to have emerged at least several hundred years ago, and then eventually spread globally—especially via blood transfusions—in the latter half of the 20th century. While the virus was mostly eliminated from blood banks after its initial discovery in 1989, it continues to spread chiefly via needle-sharing among intravenous drug users in developed countries, and by the use of unsterilized medical instruments in developing countries. The leading HCV antiviral drugs are effective but far too expensive for large-scale treatment.

An effective vaccine could eventually eliminate HCV as a public health burden. However, no such vaccine has ever been developed—largely because of the extraordinary difficulty in studying HCV’s envelope protein complex, which is made of two viral proteins called E1 and E2.

“The E1E2 complex is very flimsy—it’s like a bag of wet spaghetti, always changing its shape—and that’s why it’s been extremely challenging to image at high resolution,” said co-first author Lisa Eshun-Wilson, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate in both the Lander and Ward labs at Scripps Research.

In the study, the researchers found that they could use a combination of three broadly neutralizing anti-HCV antibodies to stabilize the E1E2 complex in a natural conformation. Broadly neutralizing antibodies are those that are able to protect against a broad range of viral strains, by binding to relatively non-varying sites on the virus in ways that interrupt the viral life cycle.

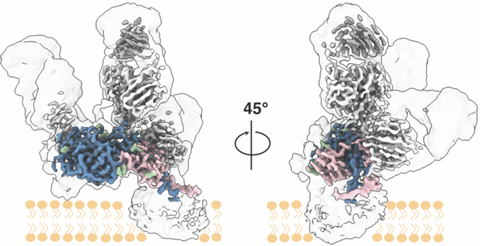

The researchers imaged the antibody-stabilized protein complex using low-temperature electron microscopy. With the help of advanced image-analysis software, the researchers were able to generate an E1E2 structural map of unprecedented clarity and extent—at near-atomic scale resolution.

Details included most of the E1 and E2 protein structures, including the key E1/E2 interface, and the three antibody-binding sites. The structural data also illuminated the thicket of sugar-related “glycan” molecules atop E1E2. Viruses often use glycans to shield themselves from the immune system of an infected host, but in this case, the structural data showed that HCV’s glycans apparently have another key role: in helping to hold the flimsy E1E2 complex together.

Having these details of E1E2 will help researchers rationally design a vaccine that powerfully elicits these antibodies to block HCV infection.

“The structural data also should allow us to discover the mechanisms by which these antibodies neutralize HCV,” says co-first author Alba Torrents de la Peña, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Ward lab.

No comments yet