Currently, most vitamins are produced in factories, either synthetically or with the help of microorganisms that are not approved for food use. These production methods require extensive and often complex purification processes (to separate the vitamin from non-food-approved materials), which are costly and energy-intensive.

Now, a team of researchers from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) has successfully produced vitamin B2, also known as riboflavin, in significant quantities using a novel, cost-effective, and climate-friendly method. The researchers employed a food-approved lactic acid bacterium, demonstrating that it can produce vitamin B2 when subjected to heat.

“I think it’s beautiful that something as simple as gentle heating and lactic acid bacteria can be used to produce vitamin B2. The method allows for food to be fortified with vitamin B2 in an easy way, for example, during the production of yoghurt or sourdough,” says Associate Professor Christian Solem from DTU National Food Institute, who led the research.

Vitamin B2 is essential for energy production and for maintaining a normal immune function. It also plays an important role in iron absorption, and deficiency has wide-ranging effects.

Fortification with B2 as part of food preparation

This innovative method integrates vitamin production into the food fermentation process. Vitamins can thus be produced and added locally. By using riboflavin-producing bacteria in food production, manufacturers can improve the nutritional value of traditional foods economically, enhancing public health while reducing environmental impact.

READ MORE: Treating the gut-brain connection with B vitamins could help treat Parkinson’s disease, study finds

READ MORE: Marine bacteria team up to produce a vital vitamin

The method differs from existing technologies by being natural—without genetic modification—and consuming less energy and fewer chemicals compared to traditional synthetic vitamin production. Fortification only requires basic fermentation tools, which are already common in many households.

Researchers stressed bacteria to produce more riboflavin

The team subjected lactic acid bacteria to “oxidative stress,” a natural pressure that compels bacteria to produce more riboflavin to protect themselves.

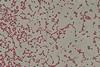

“We used the microorganism Lactococcus lactis, commonly known from cheese and cultured milk, to produce vitamin B2. Lactococcus thrives best at around 30°C, but we heated the bacteria to 38–39°C, which they didn’t like. Bacteria adapt to new conditions, and to defend themselves against the oxidative stress caused by the heat, they started producing vitamin B2,” explains Christian Solem.

The researchers optimized the vitamin production process by adding various nutrients, achieving a production of 65 milligrams of vitamin B2 per liter of fermented substrate—nearly 60 times the daily human requirement for the vitamin.

Cultural compatibility and future potential

“It would be ideal to package these B2-producing lactic acid bacteria as a starter culture that can be added to foods like milk, maize, or cassava for fermentation. When these foods are fermented using the starter culture, which includes specially selected lactic acid bacteria along with traditional ones, they automatically produce riboflavin while maintaining the traditional flavor and texture of the food,” says Christian Solem.

Many developing countries already have strong traditions of fermenting foods, which extends shelf life and reduces waste.

The method could potentially be expanded to produce other essential vitamins and nutrients, such as folic acid (B9) and vitamin B12, which are often lacking in plant-based diets. It could also be applied to various food types, including sauerkraut.

No comments yet