Researchers from the Organoid group at the Hubrecht Institute have developed a new way to grow organoids. The researchers were able to grow organoids using Invasin, a protein produced by bacteria. This study, published in PNAS on 30 December shows that Invasin offers a sustainable, affordable and animal-free alternative to currently used methods.

Organoids are small, lab-grown structures that resemble real organs. They are used to understand how organs work, how diseases develop and to test new drugs. To grow organoids, the cells need an environment that is similar to the extracellular matrix in the body. This is a network of proteins such as collagen that supports cells and gives structure to tissues. You can compare this with the need for scaffolding to construct a building.

Researchers currently use extracts from the basement membrane, a specific type of extracellular matrix, to culture organoïds. Although these extracts, like Matrigel and BME, are effective, they are derived from mouse tumors, expensive, and their exact composition remains undefined. For these reasons, researchers have sought an affordable, standardized and animal-free alternative.

Yersinia bacteria

In their search for a solution, the research team turned to an unexpected alternative: a bacterial protein. Specifically, they focused on Yersinia, a bacteria that can be found in the gut. Yersinia bacteria use a membrane protein called Invasin to attach to human cells—a clever trick that the researchers decided to repurpose.

“We started to think out of the box and try something completely different,” says Joost Wijnakker, the study’s first author. Invasin activates specific proteins on the surface of the intestinal cells that act as tiny docking stations, allowing cells to attach and grow. The researchers isolated and refined a powerful part of the Invasin protein to test whether this fragment could mimic the same functions as the proteins in Matrigel/BME.

Growing organoids

In the current study, the researchers coated culture dishes with the refined Invasin protein and showed that this allowed them to culture organoids. The versatility of this Invasin coating is remarkable.

READ MORE: Researchers unmask an old foe’s tricks to thwart new diseases

READ MORE: Researchers reveal how pathogenic bacteria load their syringes

“We were able to grow and maintain organoids long term from human intestinal and airway cells, mouse intestinal cells, and even snake venom gland cells,” Wijnakker explains. The cells maintained the ability to develop into specialized cell types. The organoids thus mimic the original organ with its variety of cell types. This is essential for accurately studying how organs develop, regenerate and respond to drugs.

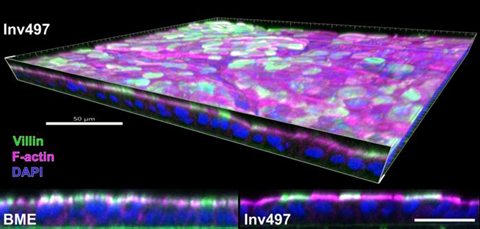

2D is the new 3D

Using the Invasin coating to grow organoids has another advantage. Organoids are typically grown in 3D structures, embedded in a gel such as Matrigel/BME. This can make them tricky to study. It’s like trying to analyze a blueberry while it’s stuck in a jelly pudding—you can’t easily reach it.

With the Invasin coating, researchers can culture organoïds as flat 2D sheets. This flat structure holds many advantages: the cells are easier to culture and examine, and they are more practical for testing many different drugs at the same time. Moreover, the 2D structure preserves the natural organization of cells. The top and bottom of a cell remain distinctly separate, as in a real organ. Intestinal cells, for example, have two distinct sides. One side is in contact with the intestinal contents and helps absorb nutrients. The other side is connected to the basement membrane. The 2D structure enabled by Invasin preserves this organization and makes both sides of the cell accessible for study.

The future of organoids

The possibility of culturing organoids with an Invasin-coating has important implications.

“We believe that Invasin represents a fully defined, cheap, versatile, and animal-free alternative to Matrigel/BME,” concludes Wijnakker. This technology opens up new possibilities for research, and will accelerate drug development. By swapping mouse-derived gels for a bacterial protein, the researchers show that even knowledge about the smallest organisms-such as bacteria-can bring about major changes in medical science.

No comments yet