Hungarian researchers have discovered unique bacterial communities in thermal waters that may help unravel the development of stromatolites, one of Earth’s oldest rock formations. These findings not only contribute to understanding Earth’s geological past but also provide valuable insights into biological and geological processes occurring in extreme environments today.

Researchers from Eötvös Loránd University, University of Sopron, and the HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geological and Geochemical Institute have made a remarkable discovery regarding the development of carbonate structures (stromatolites) formed by microbes. Their findings have been published in the prestigious journal Scientific Reports.

Ancient fossils

Stromatolites are layered carbonate structures formed by photosynthetic cyanobacteria. Dating back more than 3.5 billion years, they are among Earth’s oldest known fossils. These microorganisms thrived in vast shallow-water colonies in ancient oceans and played a crucial role in increasing atmospheric oxygen around 2.2 billion years ago during the Archaean era. Understanding their formation is significant for both ecological and evolutionary research. However, studying them is challenging because actively forming stromatolites have become increasingly rare today.

READ MORE: Stromatolite study provides new detail on the impact of volcanic activity on early marine life

READ MORE: Unearthing the secrets of living rocks

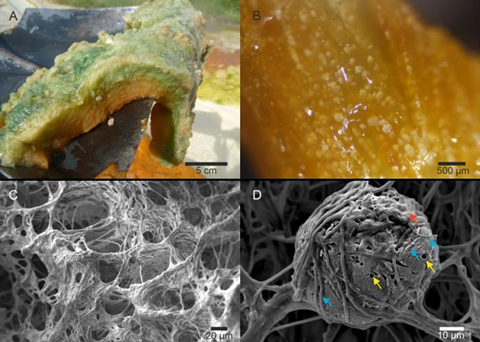

During research at the Köröm thermal spring in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County, Hungary, scientists observed biological formations structurally similar to ancient stromatolites. The thermal spring environment hosts 3–5 cm thick red and green layered biofilms, which are carbonate-rich microbial mats (Figure 1). These biofilms can thrive under extreme conditions, including low organic matter content, high salinity, significant arsenic concentration, and a temperature of 79.2°C.

Biofilm link

The researchers identified correlations between bacterial community composition, physicochemical properties, and limestone precipitation processes. They were the first to describe the similarity between currently living red biofilms and fossilized stromatolites (Figure 2).

This research significantly enhances our understanding of the geobiological processes behind stromatolite formation, both in the modern environment and throughout Earth’s history. The findings expand knowledge on biogenic carbonate formation, providing a framework for interpreting fossilized microbial structures and reconstructing past ecosystems.

Beyond offering a glimpse into Earth’s ancient past, the discovery also helps scientists better understand ongoing geobiological and geochemical processes on our planet today.

The research was conducted by Judit Makk, Nóra Tünde Lange-Enyedi, Erika Tóth, and Andrea Borsodi from Eötvös Loránd University’s Microbiology Department, in collaboration with the University of Sopron and the HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geological and Geochemical Institute.

Topics

- Andrea Borsodi

- Bacteria

- Biofilms

- Ecology & Evolution

- Eötvös Loránd University

- Erika Tóth

- Extremophiles

- Healthy Land

- HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geological and Geochemical Institute

- Judit Makk

- Nóra Tünde Lange-Enyedi

- Research News

- stromatolites

- thermal waters

- UK & Rest of Europe

- University of Sopron

No comments yet