Globally we see 600 million cases of foodborne illness, with almost half a million deaths yearly. Yet, what is most harrowing is that foodborne diseases are entirely preventable. Each year 7 June marks World Food Safety Day, encouraging global food safety awareness through open discussion to help prevent, detect and manage foodborne risks throughout the population.

Global Burden of Foodborne Illnesses

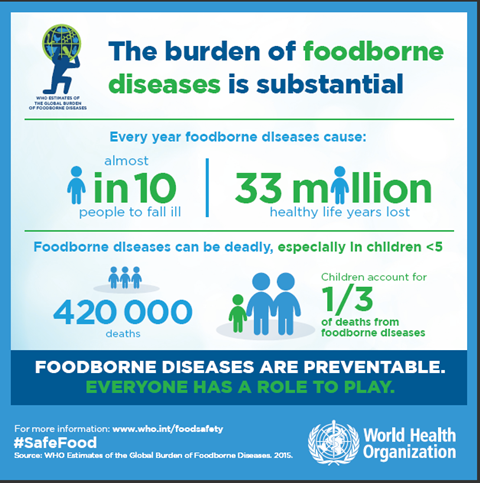

Food safety is a broad title that covers various topics, including food security, economic prosperity, and human health through food and agricultural production. The World Health Organisation (WHO) plays a pivotal role in coordinating stakeholders across the globe to work collaboratively to reduce the burden of foodborne illness. When an individual falls ill from a foodborne pathogen, the aetiology of the disease can be anything from mild self-limiting symptoms to hospitalisation or even death. There is a significant disparity as to whom is burdened by these illnesses, impacting children under five and regional variation affecting low-and-middle income communities (LMICs) most. For example, 30% of foodborne-related deaths occur in children under five, and South-East Asian and African regions are considered to have the highest burden of such diseases. In 2010, WHO estimated the global burden of foodborne illnesses to be 33 million DALYs.

Surprisingly, these facts and figures have only been produced in the last decade. In 2006, WHO established the Initiative to Estimate the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases. From this, the Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG) was launched the following year, tasked to provide quantified data for the regional and global burden of foodborne illnesses to improve control measures of food safety systems. From the collaborative efforts of the task forces, a comprehensive report was published in 2015. This report brought to light the true impact of foodborne diseases at a global level to guide policymakers to direct resources at the appropriate level, from regional to international, for equitable improvements in food safety.

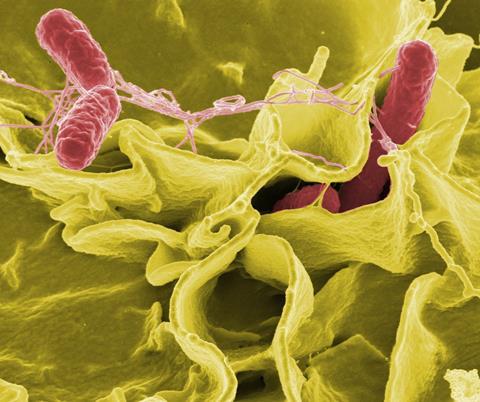

The most frequent causative agent of foodborne illness burden is diarrhoeal diseases, contributing to over 550 million cases of illness and 230 000 deaths annually. This includes norovirus, Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli and non-typhoidal Salmonella. You may be familiar with these pathogens due to the rise in food product recalls in 2022, including Salmonella-contaminated easter eggs in April last year and shellfish recalls due to possible norovirus contamination. In addition, there is a differentiation between foodborne pathogen burden between LMICs and high-income countries, with Campylobacter a significant burden in high-income countries and pathogenic E. coli more prevalent in LMICs.

Economic Impact of Foodborne Diseases

The impact of foodborne disease on the economy can be devasting. As food supply chains become more complex and serve international food demand, there becomes an increased risk of foodborne pathogens entering the chain. Economic impact covers not only the profits and losses of businesses but also government finances and individual wealth. In the US alone, food safety-related incidents cost the economy $7 billion annually; this includes removing products from shelves and paying out in lawsuits as a result of food safety breaches. In addition, with the globalisation of the food trade, outbreaks relating to foodborne illness are no longer isolated in smaller regions.

Case Study: E. coli O104:H4

From May to July 2011, several confirmed cases of E. coli O104:H4 were reported in Germany, causing a large number of cases of bloody diarrhoea and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. The outbreak was linked to Egyptian fenugreek seeds supplied to European farms. Because of the risk of disease, the European Union placed a temporary ban on the shipment of Egyptian seeds and beans to Europe whilst investigations were carried out to find the vehicle of infection. This had a substantial impact on the economy, particularly on farmers producing salad products. In general, trade in salad products was significantly reduced across Europe due to widespread concerns about the potential source of the pathogen. Due to this, the European Union compensated for the impact of the loss of trade during these months.

The World Bank study estimated that the impact of foodborne illnesses costs LMIC economies US$ 110 billion in lost productivity and medical bills annually. This highlights the disproportionate effect of foodborne illnesses, impacting LMICs much worse than in high-income countries. In many high-income countries, individuals can access medical care for free or through insurance and have access to adequate working conditions with sick pay and regulations for protecting workers if they cannot work. In addition, the devastation from preventable diseases reiterates the need for improved safety measures for prevention and disease control across the globe.

Microbiology in the Food Supply Chain

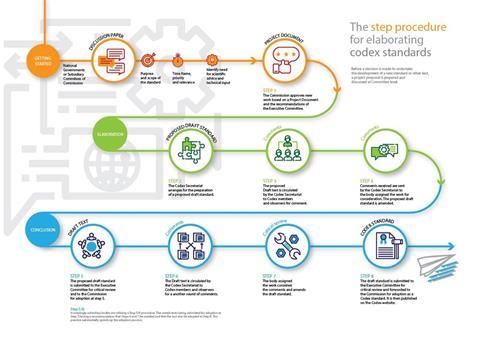

Microbiology is a vital part of the food supply chain to monitor for contamination of pathogens to prevent food spoilage and risk to consumer health. However, food safety was only standardised across the globe fairly recently. As the international exportation of food products has grown, efforts were made to unify food production processes to ensure informative guidance and regulation to improve food safety. Food safety standards are set through the United Nation’s Joint Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the WHO Food Standards Programme. Through their collaborative work, the Codex Alimentarius was established in 1963, and since its establishment, the standards have been followed by 188 member countries and one member organisation (the European Union). Founded on science, Codex reduces food-related risk through scientific research and evidence to safeguard public health.

At any point in food production lines, contamination can enter, from unclean machinery to poor storage conditions. By incorporating microbiology safety nets via testing, foodborne diseases can be prevented, reducing negative economic and health impacts on the population. Implementing diagnostic tools into the supply chain and comprehensive reporting and labelling of batches can minimise the contamination risk of microorganisms. Furthermore, complying with hygiene standards to minimise environmental cross-contamination reduces the risk of contaminated food entering circulation. ISO 18593 is a key example of a standardised microbial method to reduce the food chain’s contamination risk. Provided by the European Commission as guidelines for food safety, the food safety outlines methods of horizontal sampling using contact plates or swabs to identify culturable microorganisms within the manufacturing process. In addition, as technology advances in genome sequencing, it has become even more important to integrate whole-genome sequencing along the food chain to improve monitoring and surveillance of foodborne pathogens and disease outbreaks. This would further strengthen monitoring and surveillance by increasing the ability to rapidly characterise numerous organisms, and non-culturable organisms that are missed during traditional culturing methods.

Microbiology is crucial for food safety, providing efficient testing methods to monitor and prevent disease outbreaks. Incorporating microbial testing improves the capacity for informed decision-making for effective consumer safeguarding of foodborne illnesses and policy implementation for improved global food safety.

Acknowledging Sustainable Development Goals in Food Safety

One may believe that food safety only fits within UN SDG2 with its focus on hunger, food security, nutrition and sustainable agriculture. However, food security spans a wide range of SGDs, including SDG3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), SDG8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Securing world food safety will improve the health and well-being of populations by increasing available food which is safe to eat and, in turn, reducing the number of foodborne illnesses transmitted within the population caused by contaminated food. In addition, providing standardised food safety management frameworks, including microbiological testing, would increase employment as these microbial food safety initiatives require a trained workforce to keep up with monitoring and surveillance. Increasing job opportunities is good for individuals and their families and the broader national and international economy. Employment rates drive economic prosperity. Giving individuals wages allows for purchasing power and a virtuous circle of economic growth. Economic growth is also sustained by reducing the number of product recalls and the downstream costs associated with foodborne illness mentioned above in the article. Furthermore, with the globalisation of the food industry, we see greater export and import of food products. Hence, providing standardised regulations and guidelines safeguards consumers and creates partnerships for food exchange.

The synergy of the SDGs makes food safety everyone’s problem. Working in collaboration provides solutions; science and policy work hand in hand to drive change for better food safety standards globally.

Reducing the burden of foodborne illness

The burden of such foodborne illnesses will only go away with novel surveillance methods and changes to the policy to ensure that consumer safety is equitable. In addition, challenges in monitoring and access to safe food supplies in LMICs should be investigated further to find new education methods for increasing regulation compliance to reduce the disease burden in those communities. This is not a one size fits all solution for reducing the burden of foodborne illness; however, with collaborative efforts from members of WHO, the UN and their associated task forces in foodborne disease surveillance and food safety, there is the opportunity to work towards a future when these diseases seize to exist through education, surveillance and regulation compliance globally.

Hannah Trivett is affiliated to the National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Gastrointestinal Infections at University of Liverpool in partnership with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), in collaboration with University of Warwick. Hannah Trivett is based at University of Liverpool. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or the UK Health Security Agency.

No comments yet