A team of researchers from Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) has developed a “sponge” made of porous, formable silicone embedded in a chip, which can suck up unknown microorganisms in the environment for further research.

The findings are published in ACS – Applied Material and Interfaces.

“It is quite surprising that nobody ever thought of using medical silicone for the settlement of bacteria,” says Christof Niemeyer, Professor for Chemical Biology at KIT’s Institute for Biological Interfaces-1.

The special polymer, also used for breast implants, does not interact with its environment. It can be modified easily, is long-lived and inexpensive.

The results surpassed their expectations, the chemist says.

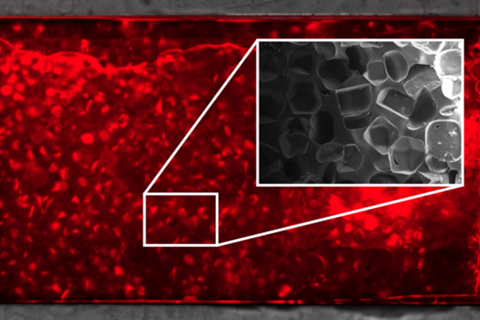

“The material can take up microorganisms from the environment, no matter how moist or dry it is. For this purpose, the silicone had to be processed to a porous, sponge-like structure,” he explains.

Microbial dark matter

Experiments revealed that this silicone sponge captures a very large range of microorganisms in its holes. In the dry air of a poultry farm, the team identified Actinobacteriota species. These microorganisms are needed for the production of antibiotics and can be applied to produce substances to treat certain cancer diseases.

“With the sponge, we can catch new bacteria that might benefit biomedicine,” Niemeyer says.

When the silicone sponge was immersed into a pool for cultivating pikeperch,researchers found many bacteria belonging to the Candidate phyla radiation group, far more than in conventional, commercially available material.

“These microorganisms account for about 70 percent of the microbial dark matter, as they have not been cultivable so far,” Professor Anne-Kristin Kaster explains. With her team at the KIT Institute for Biological Interfaces-5, she analyzed the captured microorganisms using latest sequencing technology.

The team also proved that the sponge can enrich selected bacteria, if it is prepared accordingly. For instance, microorganisms processing glyphosate were “lured” into the sponge using this pesticide. In contact with soil samples, the porous material was colonized by microbes within a few days.

To make medical silicone habitable for microorganisms, the researchers had to process the material in a new way. The team added table salt to the polymer, which was dissolved again afterwards. As a result, small holes connected by small passageways developed, creating the sponge-like structure.

For applications, the researchers then formed a “chip”, a small unit consisting of the same silicone as the sponge, but in its homogeneous rather than porous form.

“The silicone chip, that is the combination of sponge and chip, can be produced easily with standard methods in nearly any size and number,” Niemeyer says.

“The robust research tool obtained can be used in nearly any environment. There is every indication that this chip is highly suited for the systematic investigation of microbial dark matter. It opens up interesting options for the cultivation of microorganisms that could not be cultivated so far.”

The main authors have filed a patent application for the silicone chip.

No comments yet