Melanin protects the skin—the body’s largest organ and a vital component of the immune system—from the damaging effects of ultraviolet (UV) radiation. When the skin is exposed to UV radiation, melanin production is stimulated in melanocytes, with tyrosinase playing a key role in the biosynthetic pathway.

However, disruptions in this pathway caused by UV exposure or aging can lead to excess melanin accumulation, resulting in hyperpigmentation. To address this, tyrosinase inhibitors that suppress melanin synthesis have become valuable in the cosmetic industry.

READ MORE: New study explores sun’s effects on the skin microbiome

READ MORE: Smart skin bacteria able to secrete and produce molecules to treat acne

Unfortunately, some of these compounds, such as hydroquinone, have been found to be toxic to human skin, causing issues like vitiligo-like symptoms and rashes. Consequently, hydroquinone is no longer recommended for use.

Safer alternatives

The increasing demand for safer alternatives has sparked a race to discover tyrosinase inhibitors from microbes that produce compounds with low toxicity. Recently, researchers at Tokyo University of Science (TUS) identified a promising tyrosinase inhibitor from Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum, a bacterium commonly found on human skin.

The study, led by Assistant Professor Yuuki Furuyama from the Department of Applied Bioscience at TUS, was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences on July 4, 2024.

Co-authors Ms. Yuika Sekino and Prof. Kouji Kuramochi, also from TUS, contributed to the findings. Dr. Furuyama elaborated on their approach: ”Bacteria that reside on our skin and evade immune responses often become commensals, neither benefiting nor harming us. We chose to investigate metabolites produced by these commensal bacteria for their potential as tyrosinase inhibitors. These natural skin-derived products exhibit low toxicity, making them inherently safer.”

Potent compound

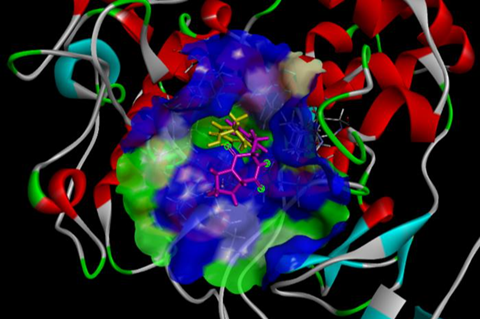

After screening over 100 skin-derived bacteria, the team identified C. tuberculostearicum as a producer of a potent tyrosinase-inactivating compound. Their assays utilized tyrosinase from the mushroom Agaricus bisporus to confirm inhibition. Subsequent experiments pinpointed the active compound as cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr). The researchers then conducted three-dimensional (3D) docking simulations to elucidate how cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) functions.

”Our goal was to understand how cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) disrupts tyrosinase activity,” explained Dr. Furuyama. “In melanin biosynthesis, tyrosinase initially converts L-tyrosine (L-Tyr) to dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) quinone, which then transforms into DOPA chrome. Ultimately, DOPA chrome polymerizes to produce melanin. Our findings revealed that cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) mimics L-Tyr, binding to and obstructing the substrate-binding pocket of mushroom tyrosinase. This interference renders the enzyme inactive.”

Dr. Furuyama emphasized the significance of their discovery: ”Our study is the first to identify and elucidate the mechanism of a tyrosinase inhibitor derived from a skin bacterium.”

Skin probiotic

The team is highly optimistic about the potential of their discovery. Scientific literature supports the non-toxic nature of cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) to human cells, underscoring its suitability as a skin probiotic for combating hyperpigmentation. Moreover, the metabolite exhibits additional beneficial properties such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities, further enhancing its therapeutic potential across various applications.

Of particular interest is the team’s success in extracting substantial quantities of cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) from C. tuberculostearicum, paving the way for potential industrial-scale production. This capability is crucial for ensuring the financial feasibility of manufacturing active ingredients on a large scale.

Despite the promising outlook, Dr. Furuyama acknowledges that there are significant hurdles to overcome before these natural active ingredients can reach consumer shelves. He emphasizes the need for extensive research to precede the widespread adoption of cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) in cosmetics. ”Before cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) can be widely used further studies are essential. Testing with human tyrosinase, which differs structurally from mushroom tyrosinase, is crucial. Detailed analyses of its mechanisms of action are also necessary to ensure efficacy and safety,” explains Dr. Furuyama.

No comments yet